Clayton Ruby died last week, and his memorial was this week. In the notice of his death, his family wrote: “In lieu of donations, go out and change the world,” which Ruby surely did.

He established himself as a leading litigator as a young lawyer in Toronto in the early 70s and as his reputation as a civil rights champion grew, Ruby was at the centre of some Canada’s most important constitutional law cases as the country’s judicial system reconciled itself to the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in the 1980s and 90s.

Ruby, a member of the Order of Canada, was a changer of not one, but many worlds. These were duly represented by the attendees at his standing room only memorial. My wife is part of the legal community, and was mentored by Ruby. I sat with her and she pointed out the surviving lions of law who had come to pay their respects and mourn the loss of a great man and friend.

My mother-in-law, who I also sat next to, is part of the literary community. She knew Clayton Ruby from his work in defence of free speech and advocacy on behalf of jailed and persecuted writers, most notably with PEN Canada. Likewise, she could point to the grieving members of the publishing and writing world who were there.

My contribution to recognizing faces in the crowd was somewhat more limited, but I believe worth mentioning as it touches another world that Clayton Ruby helped changed that might not have received the attention it deserves in many tributes to him published in other channels. In the corner of the room I recognized two tall distinguished looking gentlemen: chefs and friends Jamie Kennedy and Michael Stadtlander.

I knew Clayton Ruby primarily through my wife, and on a handful of memorable occasions, was lucky to sit around a table with him and his wife, Harriet Sachs, the Superior Court judge and legal lioness in her own right. Before I met them, I knew Ruby had a reputation not just as a fearsome lawyer, but also as one of this country’s greatest epicures. From my experience, the man lived up to this reputation completely.

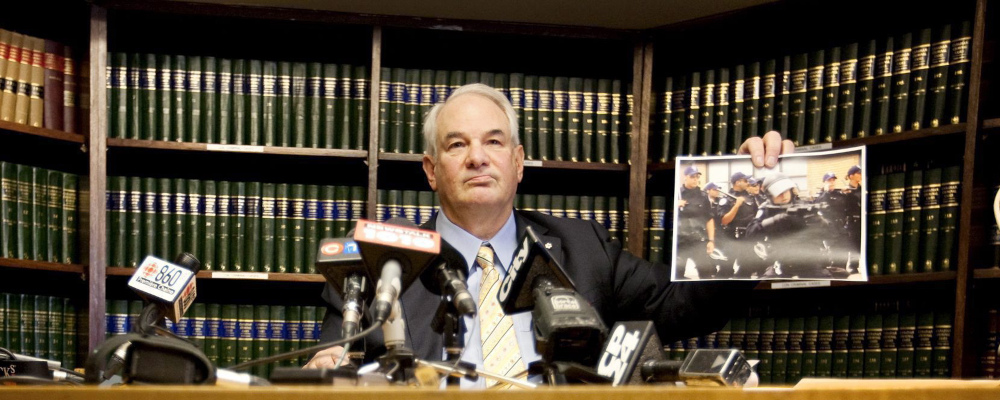

Clayton Ruby as champion of fine wine and food, and the women and men who make and serve them, came to my attention when he defended Michael Stadtlander and his wife Nobuyo against a trumped up charge of violating the liquor laws more than 20 years ago. The couple had received great attention and critical acclaim at Eigensinn Farm, their home and restaurant, which was and is a two hour drive northwest of Toronto.

The Standlanders served guests in their home and did not have a liquor license and so they did not sell alcohol. The wine one drank at dinner was the wine one brought. The local authorities devised what was clearly a sting operation whereby two undercover agents cajoled the Stadtlanders to gift them a bottle of wine from their own personal cellar, then they charged them and threatened to shut down one of Canada’s most exciting new restaurants.

It didn’t take long for Clayton Ruby to talk to the press, embarrass the local heat and make the whole mess go away. Michael and Nobuyo Stadtlander operate Eigensinn Farm to this day. The matter was a perfect fit for Ruby, whose career was made by pushing back at bullies, but it was more than that: he had skin in the game.

Ruby would have known Stadtlander and Kennedy when they cooked together, then apart in a series of acclaimed restaurants in Toronto from the mid-1980s and on. An accomplished cook himself, Ruby was a great patron of the Toronto restaurant scene as it came of age. When my writing career was more focused on the hospitality industry, and I had my finger on the hottest, newest, best, about to really take off restaurants in Toronto, it wouldn’t be unusual for my wife and I to show up to one and see Ruby already seated at the best table in the room.

I chatted a bit about Clayton Ruby’s place and importance in the pantheon of the great patrons of the culinary arts at the reception after the memorial service with Michael Stadtlander. As an aside, and something of a mischievous grin, he asked me if I had “been to the cellar?” I had, and the collection of wines I witnessed was so impressive that when Ruby asked me if I’d like to pick one the Grand Cru’s for the dinner we were soon to enjoy, I froze like a deer in the headlights and had to demure to his obviously advanced taste. The wine was superlative, and my embarrassment was quickly forgotten.

There is a golden thread running through the multitudes of tributes to Clayton Ruby’s legal career that he was always kind to his clients and generous with his colleagues. I witnessed the latter in his support to my wife as an up-and-coming lawyer. I witnessed it for myself too: he was a supportive of my various food and wine publishing and writing ventures, for which I am grateful.

I believe that one of Clayton Ruby’s great talents was to see the dignity in people who were being pushed around or otherwise not recognized. This led to him to change the way laws of Canada would be interpreted and administered, which is a big deal. It’s maybe not such a big deal to add that Clayton Ruby also saw dignity in the people who made great food and wine, when few did, and that he helped create a culture of enjoyment of the hospitality industry that we now take for granted. But he did, and those that know are thankful for it.

Recommended for You

If Canada wants stronger communities, it must make volunteering easier

After snubbing Don Cherry for over 40 years, the Order of Canada should drop politics and appoint him

In defence of wealth and money this Lunar New Year

Love, loss, and the sweet pain of sports suffering