As we await Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland’s forthcoming Fall Economic Statement, there’s a debate going on about whether the government is running a tight fiscal policy. Permit me to weigh into the debate: the answer is no.

The case in favour depends on a set of flawed assumptions including relying on an inflated benchmark due to the massive spike in program spending during the pandemic and disregarding the pre-pandemic fiscal trendline. The real story here is that the Trudeau government significantly grew federal spending prior to the pandemic, raised it to unprecedented levels during the pandemic, and has kept them elevated in its aftermath.

Let’s start with a definition. A tight or contractionary fiscal policy can refer to a budgetary surplus or, more generally, to lower government spending which in turn reduces aggregate demand in the economy.

The former definition clearly doesn’t apply here. The federal government recorded a $90.2 billion deficit last year and, according to April’s budget, is projected to run a $52.8 billion this year—though the Parliamentary Budget Office anticipates that it will ultimately come in lower.

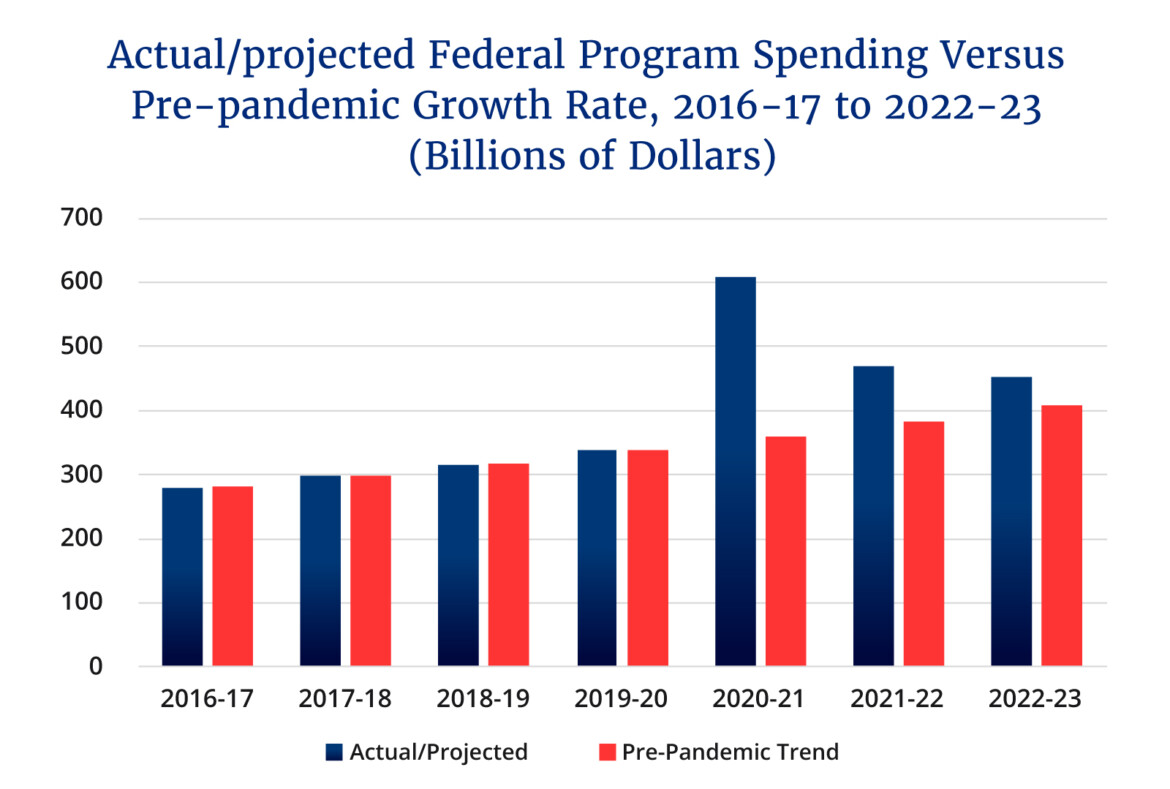

The latter definition technically applies. Program spending declined from a pandemic high of $608.5 billion in 2020-21 to $468.8 billion last year and is projected to fall further to $452.3 billion this year.

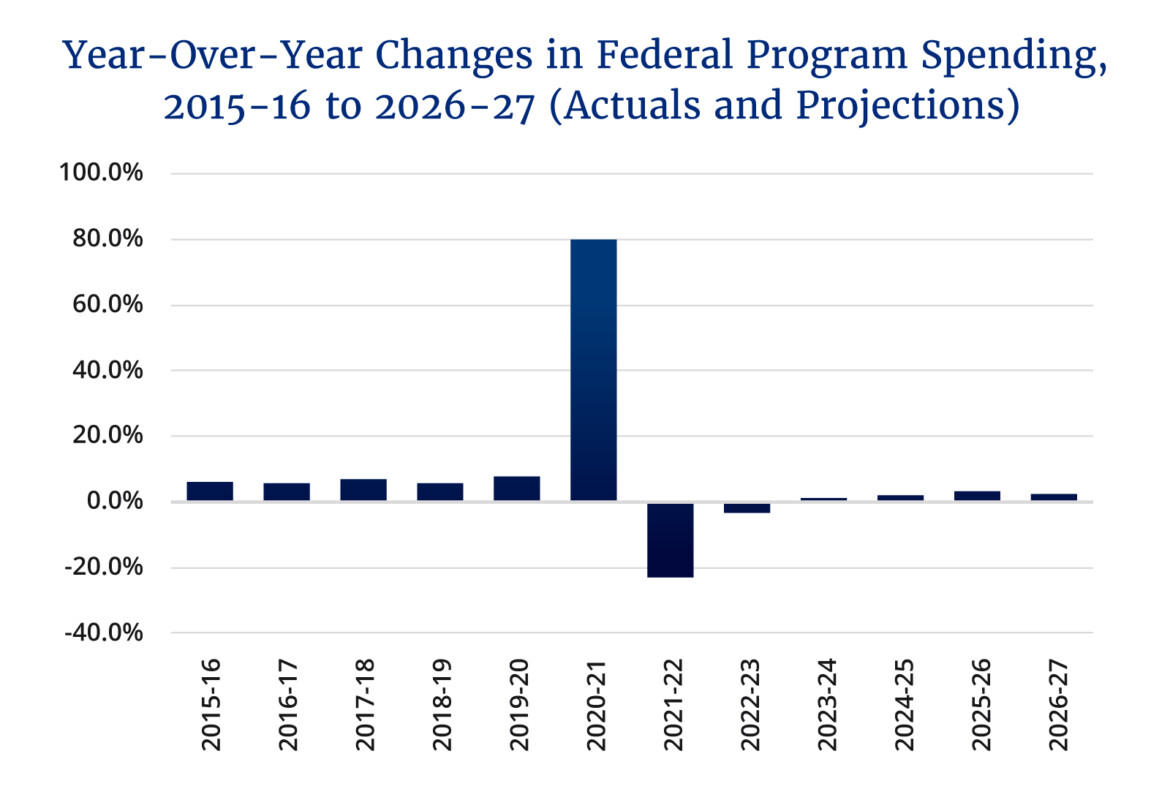

But this technical definition belies the underlying facts of the government’s fiscal policy. A major problem with the argument in favour of a tight fiscal policy is that it uses as its benchmark the unprecedented increase in program spending during the pandemic. Program spending jumped by 79.8 percent between 2019-20 and 2020-21. It’s hardly surprising therefore that spending is falling from such a historic high.

What’s surprising is that after a nearly 80 percent year-over-year increase, it’s only decreasing by about 30 percent in the subsequent two years and then is set to resume growing again (see Figure 1). In other words, a considerable share of the pandemic-induced spike in program spending has proven to be far less temporary than it’s often characterized.

Another way to see this is to try to forecast what would have happened to program spending were it not for the pandemic. As Figure 1 shows, during the Trudeau government’s first five years in office, program spending grew by an annual average of 6.4 percent. It’s important to note here that this level of sustained spending growth was in and of itself significant: it far outstripped key economic indicators such as real GDP growth or inflation over this period.

But if the government had merely kept spending growth at this rate, program spending in the current year would be $45.4 billion less than is currently projected (see Figure 2). This may provide a useful back-of-the-envelope sense of how much of the pandemic-induced spike in federal spending has persisted.

The upshot is that rather than a true contraction in program spending, we’re actually seeing a level-step increase in the overall trendline that exceeds even the Trudeau government’s own pre-pandemic profligacy. Consider for instance that program spending in 2021-22 was nearly 19 percent of GDP which (excluding the extraordinary experience of 2020-21) is the highest percentage since 1982 and the fourth highest in records dating back to the mid-1960s.

There’s also reason to believe that there are risks to the government’s own spending projections. Remember that program spending grew by an annual average of 6.4 percent in the five years prior to the pandemic. Over the five-year period between 2022-23 and 2026-27, the government is projecting program spending to grow by an average of just 1 percent.

Notwithstanding the minister’s recent talk of restraint, it seems implausible given her government’s parliamentary agreement with the New Democrats and its own predispositions that it will be able to sustain such limited spending growth through an expected recession and the next election.

To put it in perspective, an average growth rate of 1 percent is not much more than the spending growth in the last five years of the Harper government which the minister and other Liberals decried as “austerity” at the time. The point here isn’t about partisan hypocrisy but rather if one was betting his or her own money, the solid bet would be that program spending is only poised to grow even further in the coming years.

Which brings us back to the debate that we started with. Characterizing the Trudeau government’s fiscal policy as tight is the policy analysis equivalent of my toddler eating a lot of candy on Halloween night and then committing to eating slightly less candy thereafter and calling it a diet. Thursday’s Fall Economic Statement may be called various things but tight isn’t likely to be one of them.