The past year saw several international events that had a bearing on the security and the wellbeing of Canadians.

It started with the January 6th mobs on the U.S. Capitol, continued with Russia massing troops on the border with Ukraine in the spring, followed by the U.S.’s disastrous withdrawal from Afghanistan and a return of the Pakistan-backed Taliban later that summer, and ended with Russia threatening to invade Ukraine again unless the West gives in to the Kremlin’s blackmail.

The year also saw the return of Canadian hostages Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor from Chinese captivity and revealed a Chinese regime determined to enforce its own rules to challenge the international system, be it in Hong Kong, Taiwan, the South China Sea, or further afield in places such as Lithuania.

But did these developments leave an impression on how Canadians view the world? More broadly, what do Canadians think about international affairs and our role in the world? Here we present the three key takeaways from the Macdonald-Laurier Institute’s annual public opinion survey conducted in early December 2021 with the support of KAS (Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung) Canada. You can read the complete analysis and find the results here.

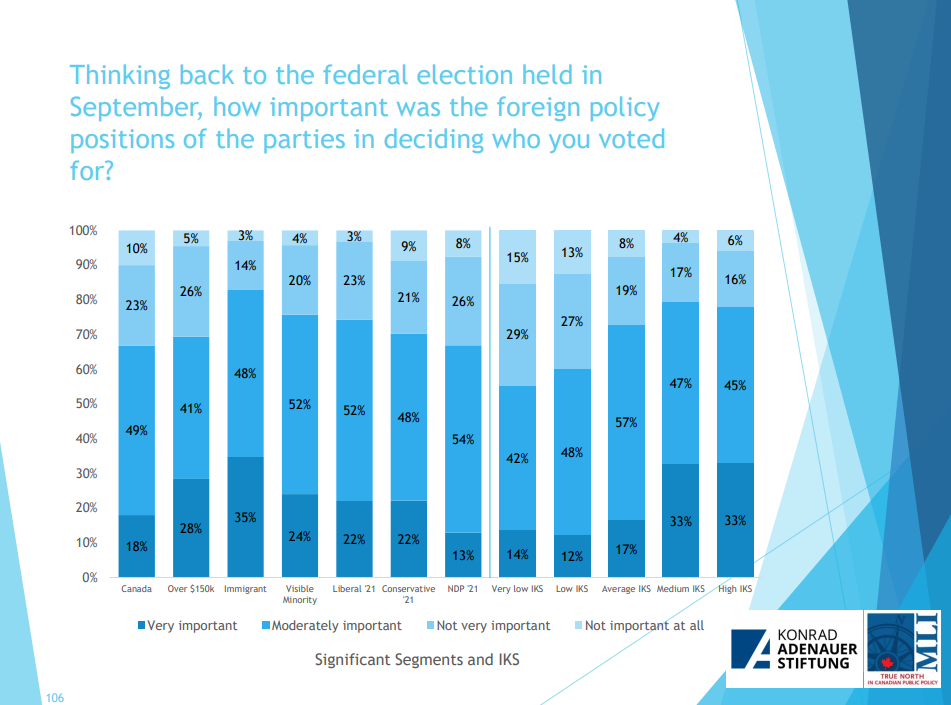

The first key takeaway: Canadians are paying less attention to international affairs and thus are less engaged with foreign policy issues compared to 2020. With vaccines and lockdowns, federal elections (where foreign policy did not feature prominently), worries over increasing inflation, residential school revelations, and other concerns on the domestic front, the attention of Canadians has been primarily domestic.

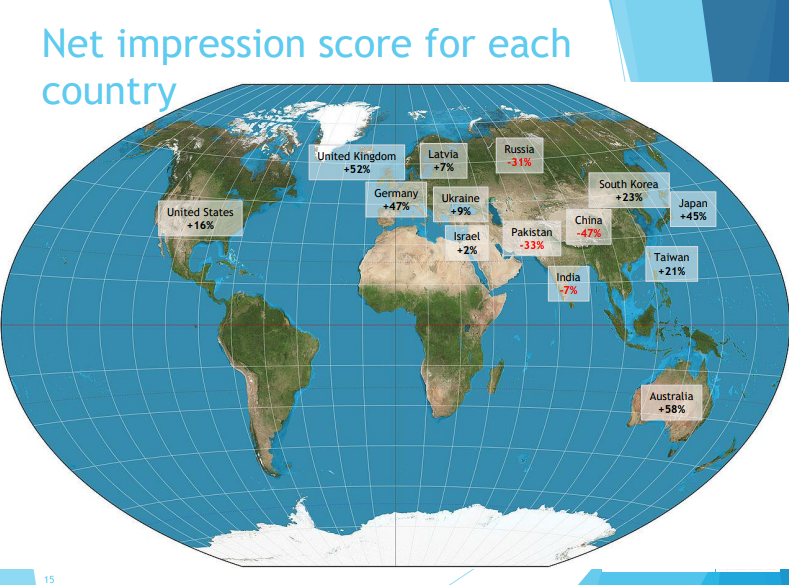

Despite this, Canadians remain clear-minded on who are our allies and who are our adversaries. Though opinions have softened, China and Russia have net impression scores of -47 percent and -31 percent respectively. On the other hand, Australia (+58 percent), the United Kingdom (+52 percent), Germany (+47 percent), and Japan (+45 percent) are the top four countries with net positive impression scores.

Second, the defeat of President Trump led to a complete reversal of Canadian public opinion toward the United States. Canadian views of the U.S. shifted from a net negative of -44 percent in 2020 to a net positive of +16 percent. The deep connection between what Canadians think of a country’s political leadership and what Canadians think of their priorities for the country presents challenges for policy-makers, whose relationships with important allies must be more resilient and based upon our long-term interests.

There is a need to have long-term and party-agnostic foreign policy that is firmly interests-based. This fact became clear after the initial euphoria among some Canadian policy-makers engendered by Joe Biden’s election had passed, leaving many of the contentious issues with the United States, especially on trade and energy, not only unresolved but actively working against the success of Canadians.

Third, there is increasing recognition of the need for a coherent Indo-Pacific strategy centred around working with democratic, like-minded regional players who are committed to a regional order premised on rules and international law. Sixty-four percent of Canadians believe that we should build closer relationships with other democracies in the region, such as Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and India. Meanwhile, on the other side, sixty-nine percent of Canadians believe that China is a threat to Canada.

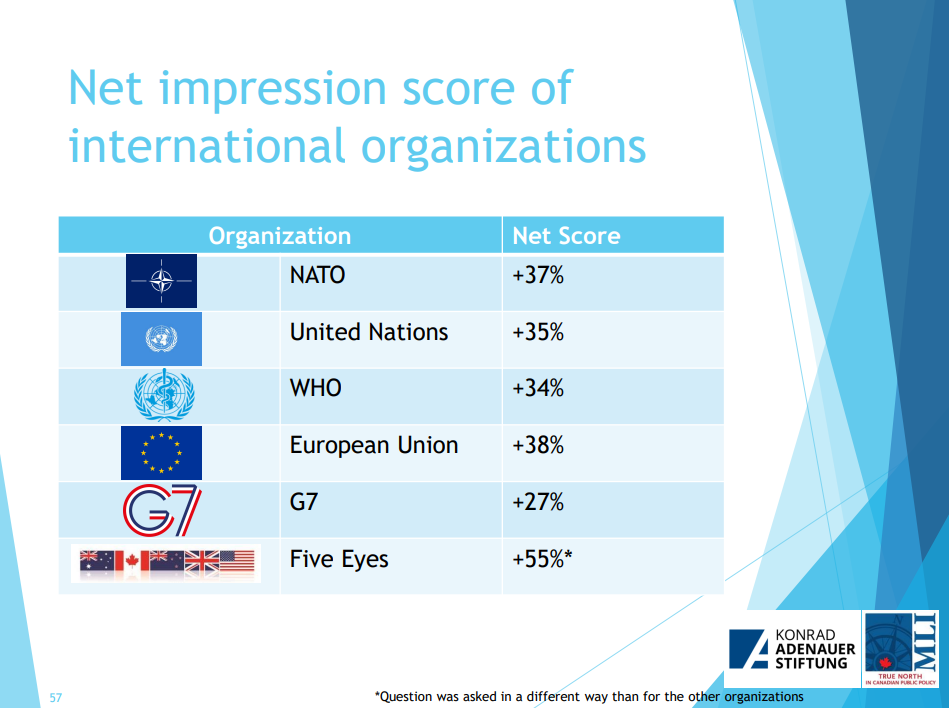

Support for AUKUS— a newly announced defense and security partnership between the U.S., the UK, and Australia last fall—is particularly strong and notable, particularly given how little it has been debated publicly. Three-quarters of Canadians think Canada should join AUKUS—a deal bigger than submarines, and much more rooted in the technological frontier of international security. Meanwhile, the Five Eyes (the security and intelligence cooperation between the U.S., UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand) remains the most popular international organization for Canadians with a net positive impression score of +55 percent.

Most importantly, Canadians largely support a stronger, more principled foreign policy that asserts our interests, stands up for democracy, and works hand-in-hand with our allies and partners. This remains the case despite the public’s decreasing engagement with foreign policy issues in 2021.

Almost nine in ten Canadians believe defending Canadian values on the world stage, such as human rights and democracy, is an important foreign policy priority. Six in ten Canadians think Canada should stand up for democracies even when there are no strategic interests involved. Sixty-one percent of Canadians think Canada should be much more active in NATO. Almost four in ten Canadians want to see defence spending increase and another four in ten believe it should at least be kept on the current levels.

While this information can help inform policy-makers, it is important to note that Canada’s actions on the global stage need to be driven by our interests and values. Where interests are aligned with public opinion, this task is easy. Where interests and public opinion diverge, this task is more challenging.

Long-term success in foreign policy for a democratic country requires a conversation between the public and political leadership that ensures our domestic needs are aligned with our international aspirations. The question now is whether Canadian policy-makers have the leadership and resilience to do so.

Recommended for You

‘The risk is worth taking’: Why increased Canada-China trade is a big boost for Western Canada

Why Canada should think twice before building more refineries

Carney defines his doctrine

Trump’s tariffs, tax shocks, and long-standing stagnation—how Canada can counter emerging economic threats: DeepDive

Comments (0)