The pandemic caused by different variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus has been associated with over 6.5 million deaths worldwide. That includes over 1.05 million in the U.S. alone and over 45,000 in Canada. In addition to known COVID-19-related deaths, the last two years have also seen a rise in all-cause mortality compared to historic levels.

Those angry against previous mandates often argue that about 99 percent of our population survived COVID-19 and very few people are dying in the current low-risk phase of the pandemic. They also speculate that many excess deaths are really due to uncounted vaccine-related complications.

On the other hand, those still struggling with the risk of infection argue that too many deaths continue to occur and we may need to mandate boosters and continue with restrictions, especially if new variants emerge. The World Health Organization has speculated that many excess deaths were due to uncounted COVID-19 deaths, primarily but not exclusively in countries with incomplete reporting systems. India alone was suspected of having over 4 million uncounted deaths.

Now, however, case counts, hospitalizations, and ICU admissions all continue to fall around the world. Life is returning to near normal. Even the ArriveCan app is at long last no longer mandated. While this news is very reassuring, the effects of the pandemic on mortality are not yet over. Daily U.S. deaths remain stubbornly above 400 per day. In Canada, there are about 32 per day.

As we move forward into this new reality, how do we evaluate why people have died during the pandemic? And how do we determine and mitigate our ongoing risk?

Death rates and their causes varied during the different phases of the pandemic. In 2020, prior to the availability of vaccines and sensible public health policy to protect older people in congregate homes, deaths were rampant in the very elderly and infirm. Rates were also higher in people of lower socio-economic status who were often deemed essential workers and thus more likely to become infected. In 2020, deaths from COVID-19 were the third leading cause of death in Canada, responsible for about five percent of all deaths.

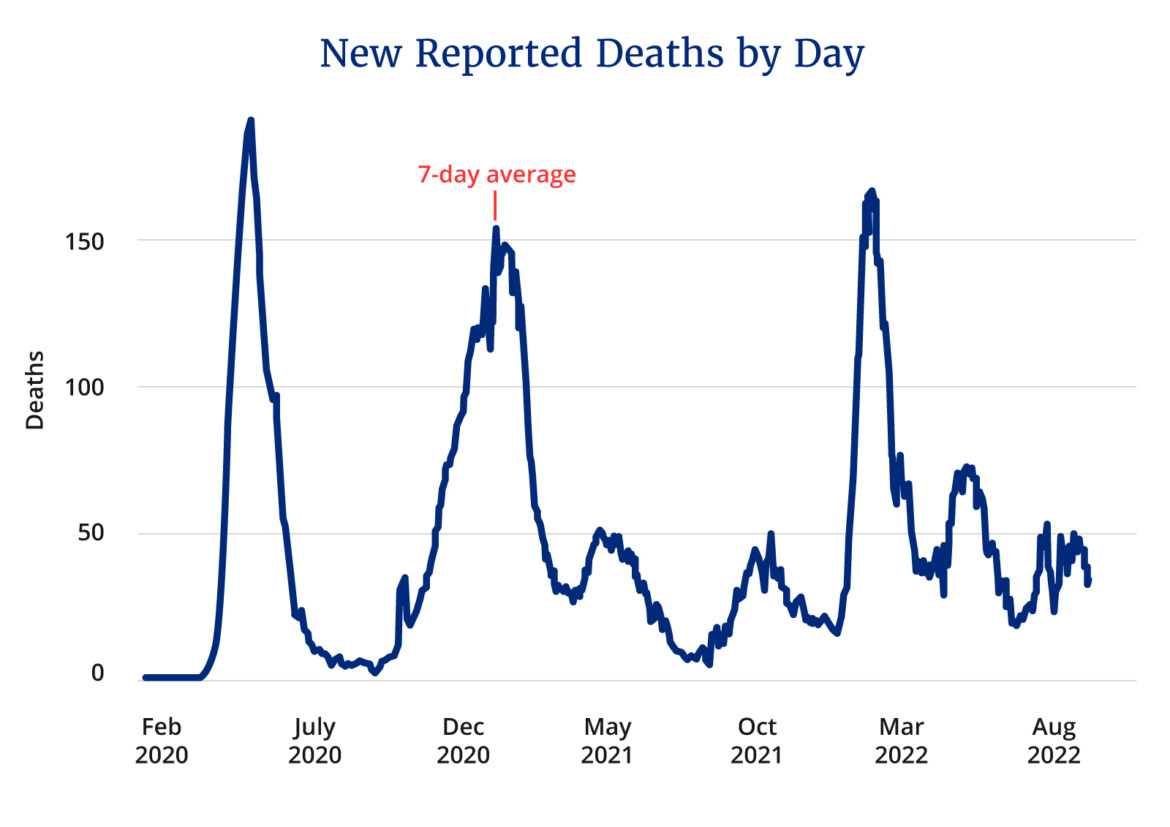

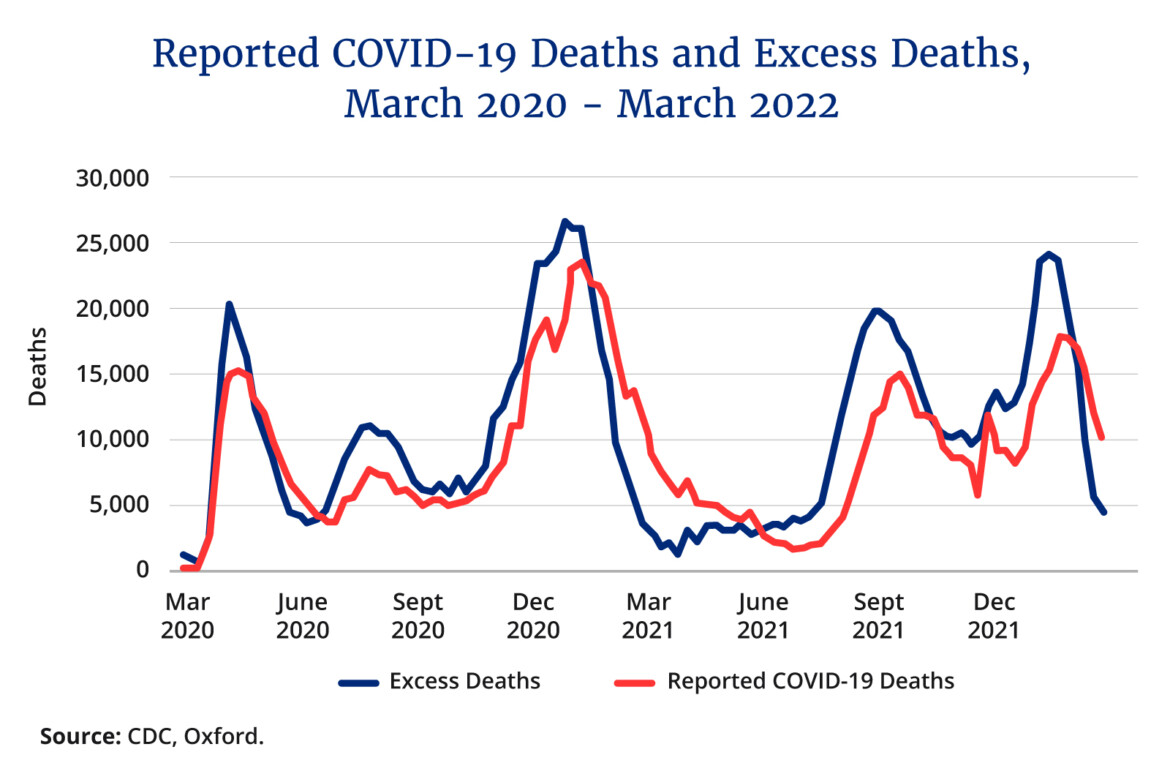

The recent graph below from the New York Times shows the whipsaw of U.S. deaths from the start of the pandemic. Canadian patterns are similar. Early deaths in 2020 were most often due to COVID-19 pneumonia. Rates decreased later that year with warmer weather and barrier protection against exposure.

Then the development of more contagious variants increased case counts and deaths in the fall of 2020 and through the winter.

As vaccination became widely available in the first half of 2021, cases and mortality declined significantly. However, in the latter half of 2021, as the highly dangerous Delta strain dominated, serious illness and death spiked again. It was primarily, however, a disease of the unvaccinated or those immune compromised.

In late 2021, the emergence of a series of more contagious Omicron variants dramatically increased cases regardless of vaccination status. While the virus was much less dangerous and did not cause much pneumonia, the sheer number of those infected led to a rise in deaths.

Now that over 90 percent of the population is relatively protected from serious outcomes by either full vaccination or previous infection and with the availability of Paxlovid for those older, the impact of infection and the numbers of deaths continue to decrease.

Who was at greatest risk of death?

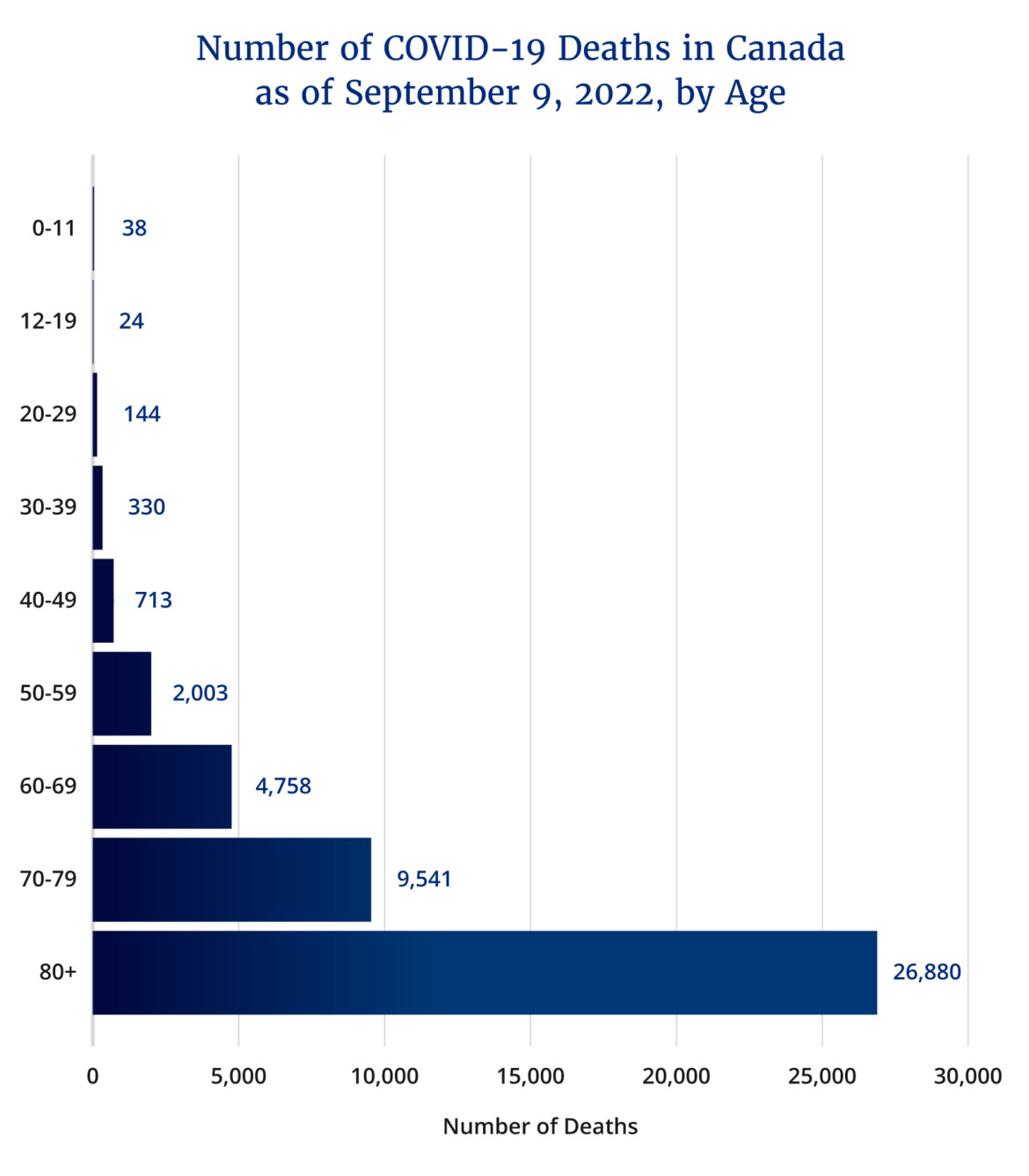

Statista reported the number of deaths by decade of age, which all along was the most important risk factor for mortality. Very few young people have died during any phase of this pandemic. Beyond age, male sex, obesity, hypertension, and diabetes were the most important risk factors.

Excess overall deaths

The total numbers of excess deaths during the pandemic were not just related to those infected. The graph below highlights excess U.S. deaths beyond direct deaths from infection.

Many argue that these excess deaths were related to uncounted COVID-19 deaths or due to the indirect effect of missed care for common diseases such as heart attack or stroke. Others argue that there are many hidden deaths due to the suppressed risks of vaccination.

Excess cardiovascular deaths

Over the past 50 years there has been a major and steady decline in death from cardiovascular disease. There was, however, a significant increase during the pandemic. Much of this increase was likely due to missed care as admissions for heart attack and stroke decreased in 2020 as people were afraid to present to hospital for life-saving treatment. In addition, increased stress and less rigorous control of risk factors likely contributed to higher event rates.

Heart attacks are often related to the effects of inflammation on the inner walls of blood vessels of the heart and brain. Infection itself is pro-inflammatory and likely accounts for some of the further increased rates. A U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs study of 153,760 people with COVID-19 showed (when compared to controls) a significant increase in heart attacks and strokes even in non-hospitalized patients.

While there is some data that vaccination can increase inflammation in the walls of arteries, there is no clear proven significant direct risk from vaccination. However, it requires ongoing monitoring.

There are also concerning reports about the increased risk of sudden death in athletes, with some temporal relationship to vaccination. The presumption is that some of these deaths may have been arrhythmic sudden death due to unrecognized myocarditis, that is heart muscle inflammation. While this may be related to vaccination in a small number of people, it is more likely due to infection itself, given the known higher risk of myocarditis from COVID-19 infection.

The pandemic has also caused a major increase in mental health issues and a heartbreaking increase in overdose deaths, most commonly in young people.

Vaccination did account for some rare serious risks. Blood clotting deaths occurred in a small number of people due to allergic-type reactions, especially to earlier viral vector vaccines. A U.S. physician reported a major acceleration of his T cell lymphoma following vaccination. While he was criticized by many as promoting vaccine hesitancy, the worsening of his cancer had validity given the stimulation of T cells by vaccination. Cancer deaths in total have remained stable.

We do require ongoing surveillance of ongoing higher rates of excess deaths and careful analysis as to whether vaccines may have some additional complications. For most deaths, there is a reasonable explanation for pandemic-related direct or indirect causes. Ongoing access to care and the danger of delayed care for serious illness remains a major concern for our fragile health-care system.

At current rates, COVID-19-related deaths now account for about three percent of all daily deaths. This may be an overestimate since many deaths reported may have been patients with COVID-19, but death was primarily due to another serious illness. Nevertheless, it remains an important challenge to limit unnecessary death. Every year about 0.75 percent of the population in North America dies, often of preventable death.

No one willingly wants to die a preventable death, yet we often ignore the major predictable risk factors. People continue to smoke, eat the wrong foods, drink too much, tan excessively, and take addictive drugs. Vaccination with bivalent boosters remains an important way to voluntarily reduce the burden of disease in those older or more vulnerable. Becoming healthier and mitigating the risk factors of unhealthy living are even more critically important for the lingering effects of the pandemic and well beyond.

Recommended for You

RCMP spending to protect MPs may have risen 112% since 2018, as Canadian politicians face greater rise in threats

Kristina Acri: The Trudeau government’s universal pharmacare is a flawed plan that will have serious unintended consequences

Durhane Wong-Rieger: Rare disease patients suffer while Canadian governments dither

Tingting Zhang: Canada has tons of doctors—yet an alarming number of people have no primary-care provider. What’s going on?