From flat earthers to 9/11 truthers, the world has seen its fair share of conspiracy theories. During the past two and a half years of the COVID-19 pandemic, conspiracy theories abound with people questioning the legitimacy of the state, from both the too many restrictions flank AND from the not enough restrictions perspective. The state, simply put, could not win. That’s if you listen to the echo chambers of social media and ignore the electoral reality that most governing parties in Canada were re-elected during the pandemic.

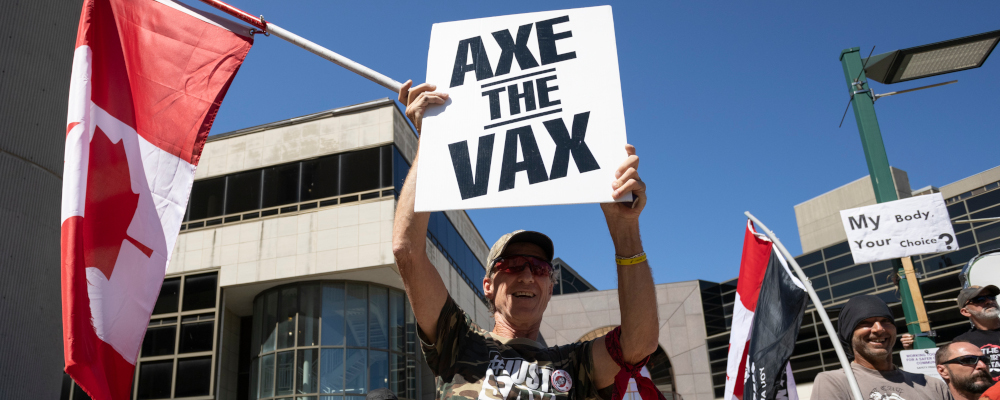

Conspiracy theories are a special category of thoughts that have permeated our regular discourse. There’s a whole anti-vaxing underworld committed to proving that we are being hosed by the likes of Bill Gates who, as some have claimed, masterminded the entire pandemic. Websites exist that discuss the vaccine as poison and some even try to track the lot numbers of the vaccine to determine whether the injection an individual received was in fact a placebo.

On the other hand, COVID-Zero proponents created an impressive online infrastructure extolling the virtues of completely shutting down life as we know it with the purported goal of making sure nobody got a viral infection. These folks are inclined to believe that government scientists and public health officials were making politically motivated decisions rather than keeping society as safe and as free as possible without overwhelming hospital infrastructure.

Everyone knows somebody in either of these two camps. There are countless stories of families who have literally been torn apart by taking sides during the pandemic for making whatever choices they wanted to make. One side felt hurt that the other side was acting stupidly. It doesn’t matter which side I’m speaking about. The one side always thought the other side was acting irresponsibly, and the differences were so significant that they were hard to reconcile.

The question that begs is this: why do people view the same situation so radically different?

In the book, Changing Minds: The Art and Science of Changing our Own and Other People’s Minds, Howard Gardner points to a few things that are important to acknowledge about the human mind. The first is that people hold on to their views because it feels psychologically safe. Our brain is preconditioned to think in terms of “us” versus “them.” We are predisposed to think about belonging to an “in” group versus an “out” group. We find attachment to what the “in” group is versus the “out” group based on feelings we develop about the situations that we are in. The “facts,” in this instance, are trivial. Emotional attachment to “belonging” is an important criterion to understand.

Ever try to get into an argument with somebody by giving them a bunch of facts of why your take is correct only to be met with a person completely unwilling to bend to the stack of evidence you have presented? While we tend to think that we are all reasonable people who reach conclusions by viewing the preponderance of evidence before us, we encounter people in our everyday lives that are polar opposite to our views who also believe that they are convinced by the preponderance of different evidence before them. We are even bound to think that if everyone was just as smart as me, they would reach the same conclusions. Yet, they don’t!

Gardner makes a different argument about the way the human mind actually works, which may help explain why people view the same situation differently. He says that we actually do not gather evidence and then make a decision based on where the information takes us. The opposite is, in fact, true. People make an emotional decision about how they feel about a situation and then use evidence to support their perspective.

The visceral reaction I am likely to encounter by stating this point, as I have with many points I have made during the COVID-19 pandemic, will only serve to reinforce how correct this take is.

Now that we know how the human mind works, let’s now discuss how every pandemic known to humans has been met with the most amazing conspiracy theories.

In his book, The Psychology of Pandemics, Steven Taylor predicts much of what has transpired with the COVID-19 pandemic before it happened. He has a useful chapter on conspiracy theories that offers many reasons why conspiracy theories are prone to happen with every pandemic.

Taylor explains that disease outbreaks commonly bring about conspiracy theories because the nature of the disease is poorly understood. Taylor points to a study that looked at medically unsubstantiated conspiracy theories in the United States that found between 12 percent and 20 percent of respondents agreeing that certain conspiracy theories had validity.

People who believe one medical conspiracy theory are predisposed to believe in other ones. That means, before the pandemic even occurred, 10-20 percent of the population was predisposed to thinking that some nefarious actors were going to be responsible for a pandemic that radically altered their lives.

The aforementioned study found that most conspiracies were fueled by a lack of faith in government institutions, suspicion of multinational corporations propagating a crisis to increase profits, large philanthropic foundations that had more than altruistic motivations, and suspicion that medical experts recommended treatment known to cause people harm.

All of this must surely sound familiar for observers of news during the COVID-19 pandemic, and many of these conspiracies are likely to continue to be part of the post-pandemic narrative of what happened during the pandemic. The facts, whatever they are, are contestable, and that is unnerving to a lot of people.

In a study of conspiracy theories on social media, several common features are evident. An important one is that those who believe in conspiracies go to great lengths to cite supposedly authoritative sources to support their views. How many times have we heard that X medical doctor said this was unsafe, hoping that we’d all somehow change our opinions?

In addition, one of the principal perspectives is that the conspirators use stealth and disinformation to convince the masses to act in ways they otherwise would not. This makes falsification of conspiracy theories unsuccessful because those that try to debunk the conspiracies with “the facts” are considered part of the “brainwashing.”

Sadly, eliminating conspiracy theories during pandemics is virtually impossible. Understanding that they exist, and why, is important in determining how best to confront them. Changing minds is difficult, and restoring faith in institutions and information takes years to establish. The time to start work on this is now.

Recommended for You

RCMP spending to protect MPs may have risen 112% since 2018, as Canadian politicians face greater rise in threats

Adam Zivo: No Dr. Bonnie Henry, drug prohibition is not ‘white supremacy’

Geoff Russ: A future Conservative government must fight the culture war, not stand idly by

DeepDive: Two-parent families: why they’re so important—and why there’s cause for concern in Canada