In July 2018, a CBC journalist sought access to the mandate letters sent by newly elected Premier Doug Ford to incoming cabinet members following that year’s provincial election. The Cabinet Office refused to disclose the letters, invoking an exemption for cabinet records under the province’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA).

After a five-year legal wrangle, the dispute is currently pending before the Supreme Court, which will soon decide whether the letters are, indeed, cabinet records. Given all the problems afflicting access to information in Canada, this question might seem critical; in fact, it is a distraction from both actors’ bad conduct. While CBC journalists might be quick to criticize government secrecy, their own institution behaves just like any other government agency, including the Cabinet Office itself.

Here is some context.

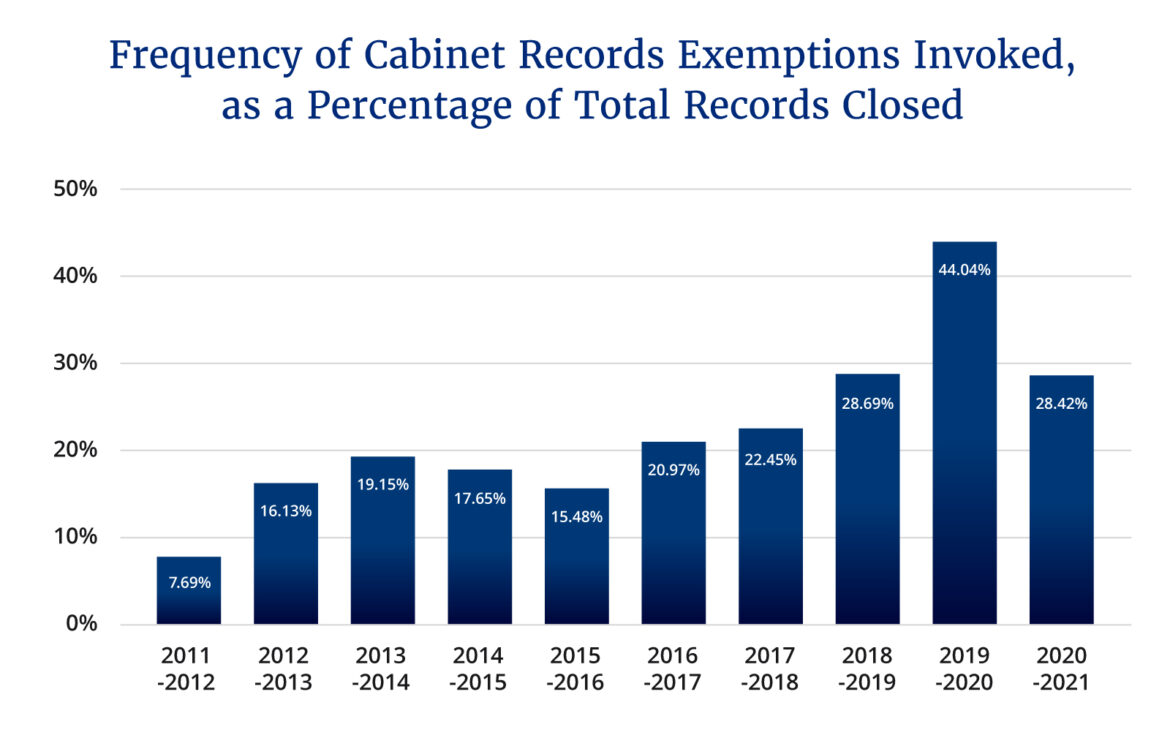

It is undisputed the Cabinet Office has gradually been increasing its use of the cabinet records exemption over the last ten years. A review of the FIPPA statistics in the annual reports on freedom of information in Ontario shows the Cabinet Office has gradually increased its use of this exemption over the previous decade.

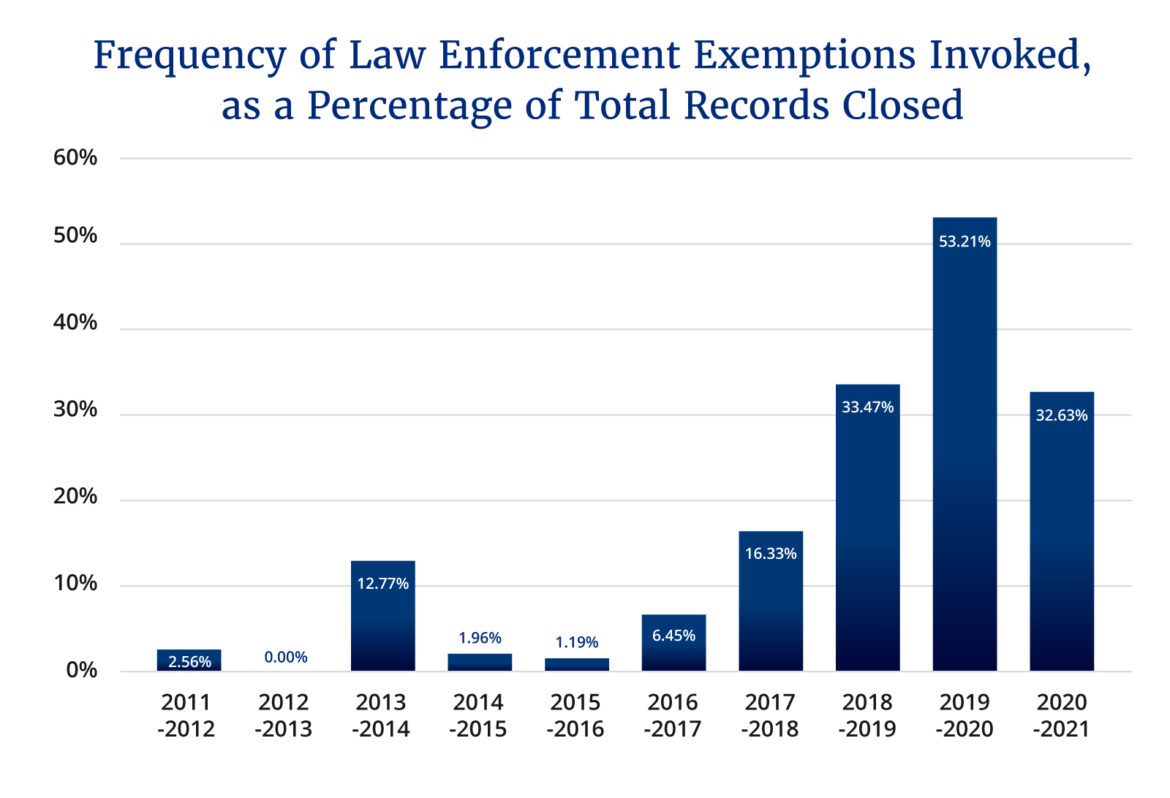

Unfortunately, recourse to the cabinet records exemption does not stand out among the exemptions invoked. The Cabinet Office has never invoked the cabinet records exemption more than any other exemption in the FIPPA, save for one year (in 2012-13). In recent years, a more worrying trend has been the Cabinet Office’s unrestrained use of the law enforcement exemption (federal institutions have been using it more, too). In the last two years alone, the law enforcement exemption has been used more than any other.

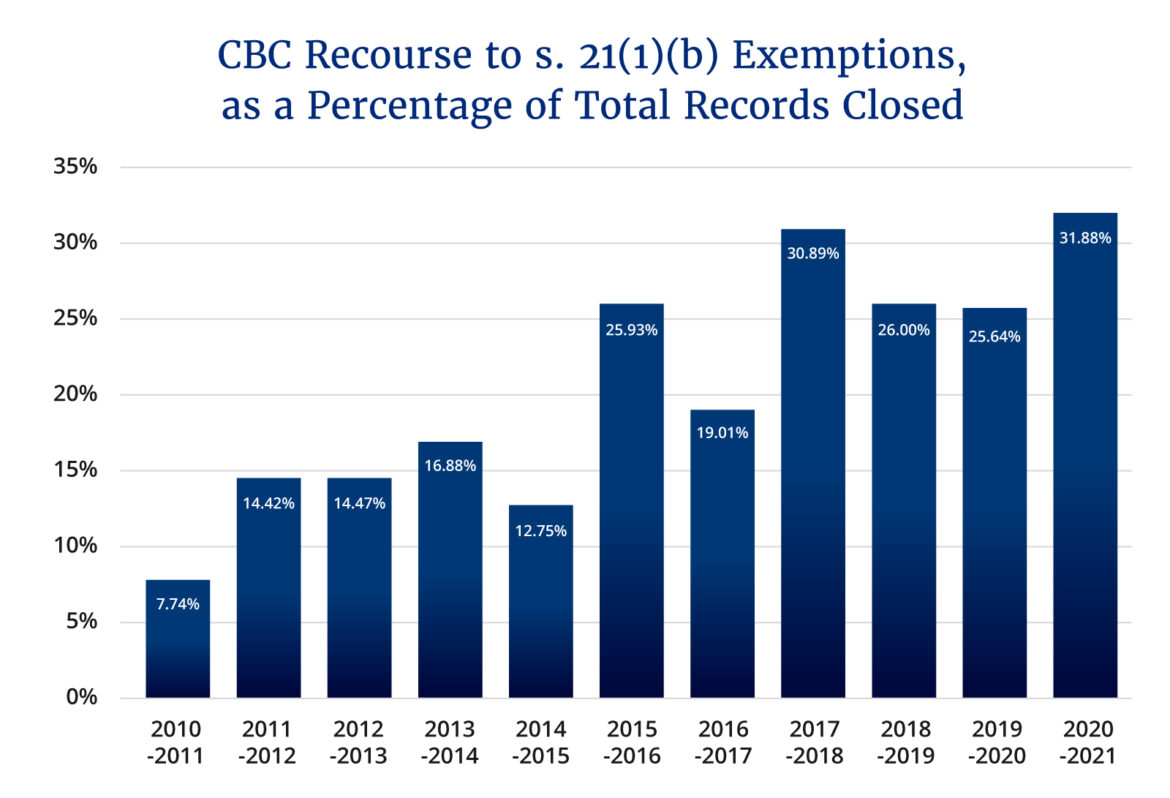

As for shielding materials from disclosure when they pertain to consultations or deliberations, the CBC itself is likelier than the Ford government to invoke such exemptions. The CBC often relies on the exemption in the Access to Information Act (ATIA) pertaining to “consultations or deliberations in which directors, officers or employees of a government institution, a minister of the Crown or the staff of a minister participate” to bar disclosure of records. This exemption is found under section 21(1)(b) of the ATIA.This exemption in the ATIA is the fourth most commonly-invoked exemption among all federal government institutions, preceded by exemptions for personal information, law enforcement, and confidences obtained from foreign governments.

Both the CBC and the Cabinet Office alike have also demonstrated a strong willingness to invoke attorney-client privilege to shield documents. Over the last ten years, the Cabinet Office and the CBC have both invoked solicitor-client privilege in their processing of access to information requests in about 10 percent of all requests processed.The Cabinet Office did so in 10.4 percent of requests processed over that period. The CBC, in 9.7 percent of requests processed.

Even with their similar track records, the CBC has not been shy to go on the attack against the Ford government for its use of attorney-client privilege. Last August, the CBC published an article stating the Ford government would not reveal how many hours it spent fighting to keep mandate letters secret. When I requested the same information from the CBC under the ATIA—namely, “[h]ow many hours have CBC lawyers spent on the mandate letters cases before the Privacy Commissioner, Divisional Court, [the Court of Appeal for Ontario], and now the [Supreme Court of Canada]”—this information was not forthcoming.

After I submitted the request by mail (the CBC only accepts payment for access to information requests by snail mail), they promptly emailed me to confirm receipt and issued a 90-day processing delay. When I explained to them CBC News had recently published an article shaming the Ford government for not providing this exact same information, they promptly released the information, confirming its external counsel had spent 390.2 hours on the case. When I went back to the Cabinet Office to request their total hours in light of the CBC’s newfound forthcomingness, they told me to contact the Ministry of the Attorney General, which did not respond to my request for this information.

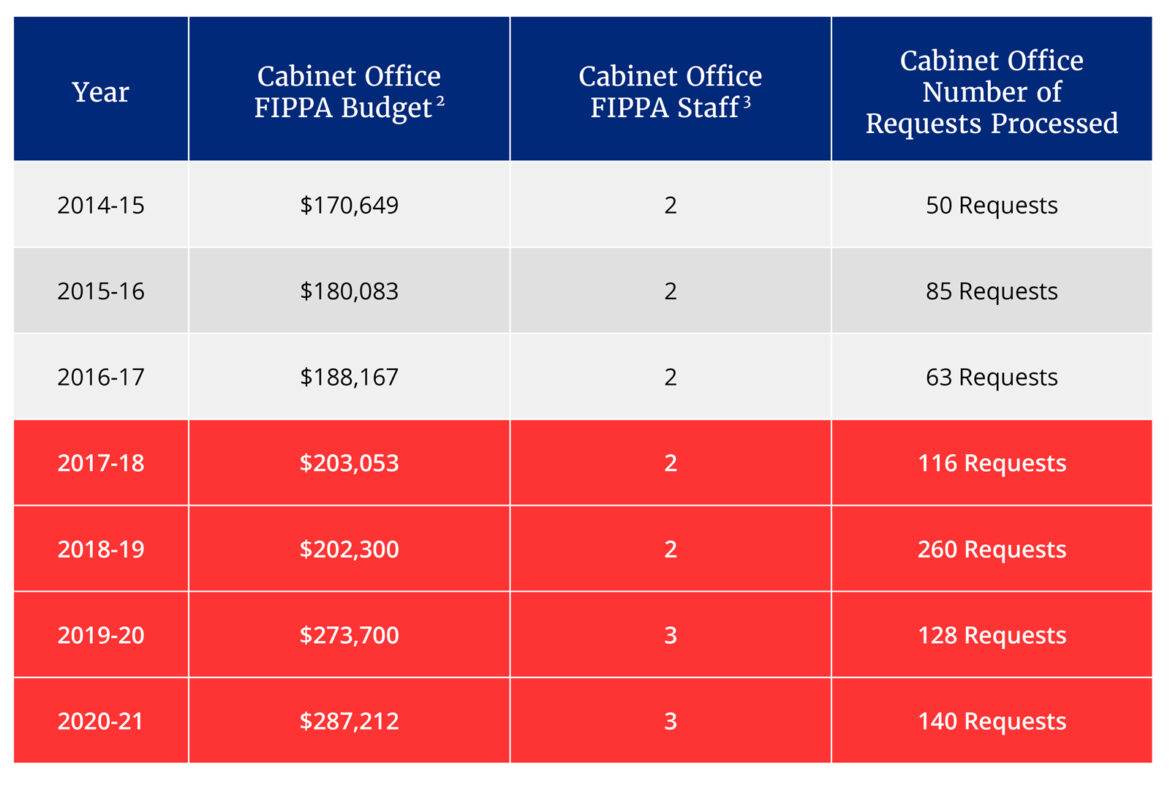

Money on these programs is not always wisely spent. Even with more funding than the Cabinet Office, the CBC generally runs its access to information program less efficiently. Although both entities have received approximately the same number of requests during the last four years, during that period, they spent approximately three times as much as the Cabinet Office and had variously two-three times the number of staff to process the same number of requests (and sometimes less).

Here is a breakdown of the Cabinet Office’s budget and staff, compared with the number of requests it processed over the last seven years, with specific attention placed on the last four years:

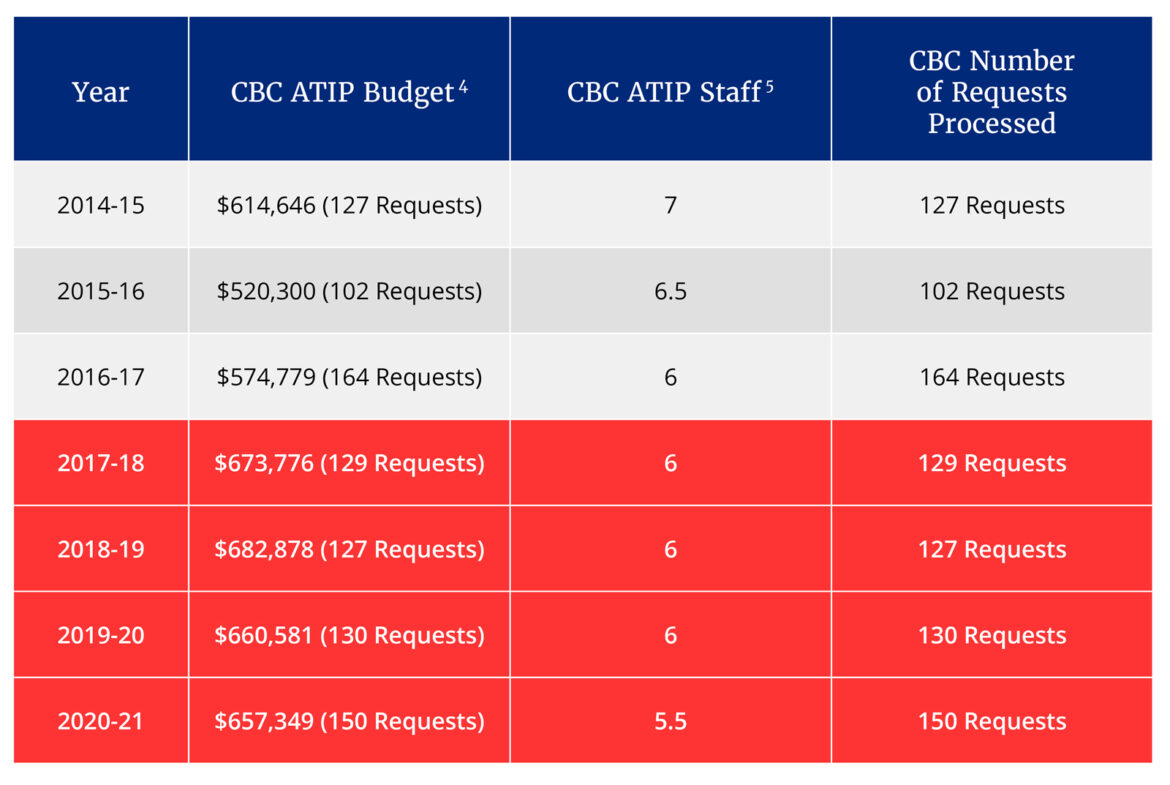

Here is the same information for the CBC:

Consider what this spending delivers. The Cabinet Office outperforms the CBC in processing requests more quickly. The Cabinet Office closed more requests within the statutory 30-day period (an average of 74.4 percent over a ten-year period) than the CBC did (an average of 62.9 percent for the same period), even with the CBC’s additional resources.

Likewise, the Cabinet Office achieved a ten-year average of 91.8 percent for closing requests within 60 days. For its part, the CBC’s average was 78.8 percent. This track record renders somewhat ironic the CBC’s arguments in its pleadings to the Supreme Court that “access delayed is access denied.”

It should look in the mirror.

One area where the CBC shines in comparison to the Cabinet Office is in proactively making available some processed access to information requests online. For its part, the Cabinet Offices does not make any processed requests available on its website. When I asked for all processed requests from the Cabinet Office, they responded by telling me I could submit an eRequest for this information at a cost of $5 per request. To obtain all requests from the last five years (707 requests), this would cost $3535, plus processing costs.Under the Ontario legislation, institutions can charge $7.50 for every 15 minutes spent “searching” for the record.

The foregoing shows that deep-rooted problems with the performance of access to information make the substantive question about the proper legal consideration of the mandate letters as cabinet records a sideshow.

As for what will happen if the Supreme Court concludes the mandate letters are not cabinet records, the answer is: not much.

Little would stop the Ford government from reforming the relevant legislation to mirror the ironclad protection of cabinet confidences that exists at the federal level (where they are an exclusion—not an exemption subject to meaningful oversight and review). Blanket exemptions from the federal government under this exclusion are already a significant problem. For example, the federal government has adopted dozens of secret cabinet orders that have been shielded from disclosure.

Reducing the scope of the cabinet records exemption in FIPPA is also likely to encourage the Cabinet Office to find justifications for nondisclosure elsewhere. As the federal government’s conduct during the Public Order Emergency Commission demonstrated, even when governments are willing to break cabinet confidence, they have recourse to other evidentiary tools to bar disclosure, such as attorney-client privilege. Canadians still do not have a proper understanding of the advice given to the federal government that justified the invocation of the Emergencies Act due to this type of evidentiary rule.

The Ontario government could also continue to use costs to erect barriers. These costs can be prohibitive for journalists, especially freelance journalists. As noted above, even accessing old requests comes with prohibitive costs. Making new ones is also onerous. For example, there is nothing to stop a journalist from requesting all cabinet records more than 20 years old from the Cabinet Office—since records otherwise protected as cabinet confidences are not protected if they are over twenty years old, under the relevant legislation—but the costs of doing so are prohibitive. Little would stop the Cabinet Office from continuing to use these fees as a procedural cudgel.

Furthermore, even if the SCC does find in favour of the CBC, such a finding may discourage the government from drafting mandate letters in the future at all—further undermining the implicit “duty to document” that is already under significant attack—or simply drafting them differently.

Experts have also cautioned against viewing mandate letters as not covered by the exemption for cabinet confidences. Mel Cappe, a former clerk of the privy council and president of the Institute for Research on Public Policy, and Yan Campagnolo, Canada’s leading expert on cabinet confidences, have urged the maintenance of the mandate letters’ confidentiality.

“Forcing the disclosure of mandate letters won’t necessarily lead to greater transparency in the sense that some information will be lost,” Campagnolo has said. “Something will be lost in the process.”

To be sure, the fight over the mandate letters may eke out a small win. For the CBC, victory would bring Premier Ford’s government into alignment with his predecessor, Premier Wynne, who published her letters, and Prime Minister Trudeau, who has also done so—governments formed by political parties to which the CBC is rather overtly aligned, given the ties between its current management and the Liberal Party. For the Ford government, a win will stick it to the CBC, which many Conservatives are intent on dismantling.

Neither outcome will fix a broken access to information system whose problems go much deeper.

Recommended for You

‘He’s meeting the mood of the country’: Hub Politics on whether Carney is dismantling Trudeau’s policy legacy

‘Snitch lines are a terrible idea’: The Full Press on Trump’s new plan to have Americans report on journalists

Fixing industrial carbon pricing makes sense—for both Alberta and Canada

Stolen Canadian cars are ending up all over the world—will we finally do something about it?