Last year’s Indo-Pacific Strategy earned the Trudeau government praise for its clarity and insights about Canada’s policy vis-à-vis China in particular and the Indo-Pacific region in general. It was widely seen as a new, more pragmatic foreign policy rooted in Canadian interests and a realist understanding of the geopolitical context.

The only major omission was the economic and environmental opportunities to leverage Canada’s natural gas resources to help our Asian allies meet their growing energy demands. LNG exports ought to be a crucial linchpin of the government’s regional strategy.

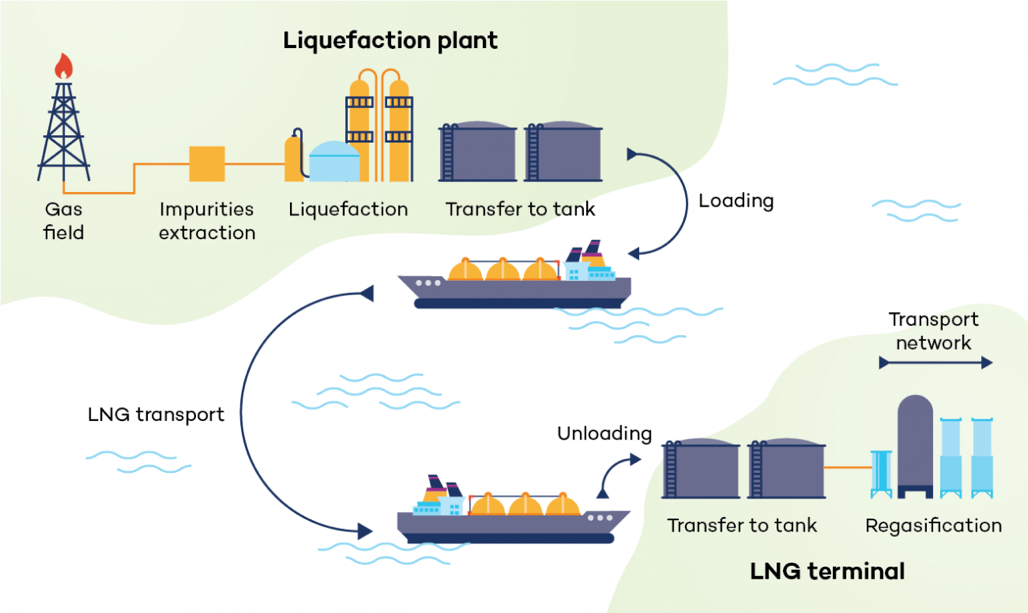

For those unfamiliar with the concept, LNG refers to the process of chilling natural gas into its liquid state, which is a crucial step in its transportation to overseas buyers. Exporting LNG to Asia would hit three of the five major objectives in the strategy: trade and investment; a sustainable and green future; and partnerships. It makes sense, except for the fact that we can’t technically make it happen. Canada still lacks the infrastructure required to complete the LNG process (pumping gas to a port, chilling it into its liquid form, and sending it overseas to buyers), and is therefore trapped in the North American market.

It prompts the obvious question: why does Canada, the fifth-largest natural gas producer in the world, lack this crucial infrastructure?

At a recent high-level U.S.-Canada Summit in Toronto, Greg Ebel, president & CEO of Enbridge Inc., squarely put the blame on permitting. While this is true, it’s important to pull back the curtain and explore what exactly is holding us back from developing the infrastructure.

To start, the world uses a lot of natural gas, and regasification infrastructure plans in Europe and Asia suggest it is going to use a lot more. One of the reasons for this is that many informed observers see natural gas as a bridge fuel to the low-carbon future, especially in countries like China, Japan, and India, where carbon-intensive sources like coal still dominate the energy mix. In this way, while it has been rightfully acknowledged that gas development could put upwards pressure on Canada’s provincial and federal climate targets, LNG trade could have the net effect of lowering total global emissions.

Canadian natural gas has three main advantages here: Kitimat, B.C.’s lower average temperature provides energy efficiency advantages over the U.S. Gulf Coast (USGC), Qatar, and Australia; Canadian LNG projects have a far lower carbon intensity than the global average; and the direct route from the Kitimat port to Asian markets would shave about 10 days off the shipping time from the USGC, saving labour and fuel costs while reducing emissions.

Even though Canada’s natural gas abundance and high environmental standards make it desirable, while also providing high-paying jobs and boosting GDP, we lack the infrastructure to compete on the global market. LNG Canada is the closest project to completion (about 75 percent) and is not expected to be operational until 2025. There appear to be three major underlying challenges that have contributed to the LNG problem in Canada.

The first relates to economics and engineering. It’s uneconomic to pipe natural gas from the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin all the way to the East Coast for export to Europe. The recent Repsol LNG cancellation in Saint John, New Brunswick was a case in point. That leaves the West Coast. What is already a great engineering challenge is then magnified by the rugged nature of BC’s North Coast, through which hundreds of kilometres of pipeline must weave. One 1.4-kilometers stretch of the Coastal GasLink pipeline with a 700-metre change in elevation required a cable crane and gondola system to transport workers and pieces.

The second relates to relations with First Nations communities, who have significant influence on the construction of linear infrastructure projects through unceded lands in Northeast B.C. While some First Nations groups like the Lax Kw’alaams have voiced opposition to LNG projects, others like the Haisla Nation are supportive (the Haisla Nation were recently announced the majority owners of the $3-billion Cedar LNG project in B.C). There have also been criticisms of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAF) for not having engaged in meaningful consultations with First Nations on large-scale energy infrastructure projects. The Federal Court of Appeal’s overturning of the Northern Gateway project proposal (2016) and the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project (2021) both cited this as the main issue. The failure to abide by a constitutional duty to consult First Nations groups is both a blow to energy infrastructural projects and a stain on Canada’s reconciliation efforts.

The third challenge relates to stringent environmental regulations in B.C. Because the climate policy space is so dynamic, LNG investors and shareholders must abide by current environmental regulations while also working to anticipate new ones. As a testament to this, the province just announced its new energy action framework, requiring all proposed LNG facilities in or entering the environmental assessment process to pass an emissions test with a credible plan to be net-zero by 2030. This would be great if there was clean hydroelectricity available to power the liquefaction terminals that otherwise use natural gas. However, there isn’t adequate transmission infrastructure to get clean electricity to those facilities. B.C. Hydro’s own CEO estimates that it will take eight to 10 years to devise and construct such a major transmission project. Unless my math is incorrect, there are only seven years between now and 2030, making it extremely difficult to meet the regulatory requirements.

There exists a conundrum: while hitting high environmental standards would make Canada’s LNG more desirable on the global natural gas market, it necessarily takes longer to meet these conditions, which leads to a slower pace of infrastructure development. As time passes and environmental regulations become more stringent, there is a risk of falling into a cycle that prevents both the completion of LNG infrastructure projects and any raising of environmental standards for global natural gas trading.

So, what is there to do about it? Besides untangling the permit web, here are a few suggestions.

The federal government needs to clear the air on their support (or lack thereof) for LNG projects in Canada. The use of language in the Indo-Pacific Strategy like “energy infrastructure and energy export” without explicitly mentioning “LNG” ultimately depresses investor confidence, which is critical considering the additional expenses incurred from engineering challenges and electricity transmission infrastructure expansions.

It is also clear that First Nations communities are key to the successful completion of any LNG project. It is unclear whether CIRNAF’s 2011 version of Guidelines for Federal Officials to Fulfill the Duty to Consult has been updated with recommendations from the HoC Standing Committee on Natural Resources 2019 Report, “International Best Practices for Indigenous Engagement in Major Energy Projects: Building Partnerships on the Path to Reconciliation.” Beyond that, rather than simply working to achieve a constitutional duty, economic partnerships and co-ownerships with First Nations should be promoted in all LNG development projects.

Finally, we need to rapidly solve the clean electricity delivery problem to B.C.’s North Coast. If B.C. Hydro can’t build transmission infrastructure in time, perhaps there are other options, like nuclear. Small modular reactors are expected to be a source of reliable, energy-dense, emissions-free energy for locations too remote to deliver hydroelectricity. That said, they cost between $200M and $300M, and the first one in Canada isn’t expected to be constructed until 2028. Nonetheless, in the absence of regulatory changes, new LNG projects will require a fast-tracking of innovative clean power solutions.

The enormity of the LNG problem necessitates bold solutions. Failure to act risks missing a valuable opportunity to boost GDP, advance Indigenous reconciliation, bolster international relations, and accelerate the global transition to lower carbon energy.