The experts seem absolutely certain of one thing: that the Alberta government is clueless.

The Globe & Mail recently released a story that claimed that the government of Alberta was planning to “broaden the circumstances under which people with severe drug addictions could be placed into treatment without their consent.” Yesterday’s campaign announcement from the United Conservative Party confirmed this reporting and outlined the party’s plan, if re-elected, to grant families, legal guardians, and police the “last-resort” right to refer addicts to treatment in cases where they are considered a harm to themselves and others and are likely to keep reoffending.1The UCP addictions plan also promises a “recovery-oriented system of care” and includes increased funding for addiction treatment centres and mental wellness centres.

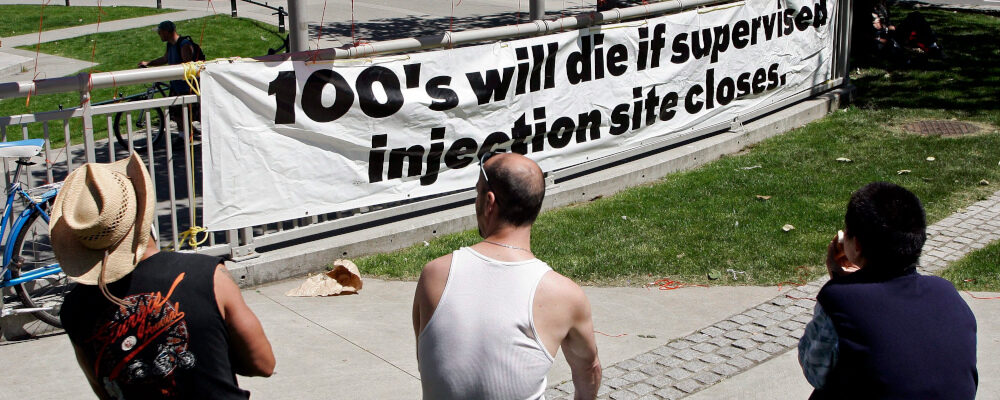

The idea isn’t new. Even British Columbia’s NDP premier David Eby recently mused about adopting a similar approach. The epidemic of drug overdoses and the problem of mass homelessness with its ties to addiction and mental illness is pushing governments of all stripes to think about what can be done.

Yet the uniformity of the expert and media response is striking.

To enforce treatment is many things, we are told, and none of them are good. Forcing someone into treatment is apparently just like torture. That’s according to Euan Thomson, the head of a harm reduction organization. “They’re put into severe withdrawal by going into these [treatment programs],” Thomson argues, “so it really is like torture.”

Or it’s seen as a violation of basic civil rights. Lorian Hardcastle, a law professor at the University of Calgary has argued that enforced treatment is “a violation of your rights to…life, liberty and security of the person”. For what it’s worth, this is the same professor Hardcastle who is on the record arguing that vaccine mandates don’t violate Charter rights even though they too were a form of mandated medical treatment.

All the experts upset at the Alberta plan share a similar harm reduction approach. Harm reduction is ostensibly meant to reduce the personal health and social costs of addiction. It aims not to stigmatize addicts (even my use of the term “addict” might offend proponents). Most importantly it is not even about getting drug users to necessarily stop using drugs—certainly not if they don’t personally want to stop using. These experts claim that their approach is supported by the best scientific evidence and that it genuinely minimizes drug overdoses or, as advocates increasingly insist on calling them, drug “poisonings.”

Should we then just trust the experts?

If it hasn’t worked yet—if our streets and downtowns are filled with tents and needles, with drug users walking out into traffic as if a busy street is no different from a soccer field, and if the numbers of those using drugs and suffering overdoses is not in fact diminishing—should we just sit back and assume that this cadre of experts will be right eventually? Perhaps we just haven’t given it enough time yet? Or maybe things will improve if we move forward with “safe supply”—that is, turning the government into a legal pusher of hard drugs?

This might all be fine if it weren’t for the fact that we’ve lived through several years of realizing just how politicized the field of public health expertise actually is. Gathering in large groups would spread COVID-19, we were told—unless you were gathering in a Black Lives Matter protest in which case, it’s all good. We should “follow the science”—unless, that is, the science showed that it would be fine to keep schools open because kids weren’t at serious risk from COVID-19.

In other words, the uniformity of expertise might be less worrisome if we could trust that experts valued truth ahead of politics. But that’s not the case. Instead, what we have is a group of experts who seem to be the intellectual equivalents of Henry Ford’s Model T: you can have all the expertise you want, as long as it’s a shade of harm-reduction.

We know just how ideologically insulated our sources of so-called expertise have become. As a colleague and I showed in our report for the Macdonald Laurier Institute last year, our universities have become intellectual silos that vastly overrepresent left-wing viewpoints. Those with alternate perspectives self-censor at alarmingly high rates.

This matters for public policy. People with different political orientations think differently about morality. Progressives have a generally rosy view of human nature based on an idea of the innate perfectibility of humans. They also increasingly focus on the virtue of victimhood above almost all other moral concerns. As Jonathan Haidt pointed out, progressives tend to be clueless about other kinds of moral matrices, often interpreting different moral choices as either being stupid or evil.

When we shape public policy it helps to test progressive solutions against other options, especially those based on more cautious views which assume the weakness of the individual, the darkness that we all contain inside ourselves, and the fact that we sometimes need to be saved from ourselves.

The intellectual debate about addiction also needs to account for the social costs of rampant public drug use and addiction. It needs to think about the social costs of children being raised in cities where it’s normal to have drug users openly out-of-their minds on downtown streets—or where the public library is a way station for men and women who haven’t showered in weeks and who leer at patrons.

The behaviour of individuals around us shapes what we see as acceptable. To the extent that harm reduction works—by de-stigmatizing drug use—this is itself a social problem. There is a danger of a cascading descent into social degradation where the terrible choices that addicts make become normalized and not stigmatized. As progressives seem to acknowledge in other areas—most dramatically in dealing with racism—stigma is socially useful. It indicates social disapproval. Would harm reduction activists suggest the same approach for hate crimes, suggesting we need to create reading rooms for racists stuffed with copies of Mein Kampf and old VHS tapes of Birth of a Nation? After all, if you follow their logic, we need to listen to the addicts and not violate their Charter rights.

Clearly, this approach wouldn’t be appropriate in the case of hate crimes and we ought to listen to those who see similar problems adopting the same approach with drugs.

Where is the Canadian version of Michael Shellenberger who has brought such dynamic debate to the United States? In his book San Fransicko, he exposed how a so-called progressive approach to urban problems had contributed to the explosion of homelessness and drug overdoses in San Francisco, hurting the people the advocates claim to want to help.

Canadian federalism allows us to test various public policies in different jurisdictions. It’s one of the benefits, amidst the many drawbacks, of federalism. We ought to be keen to allow provinces to test out decidedly different approaches to the addiction crisis.

Harm reduction advocates emerging out of the homogenous cookie-cutter world of academia offer one solution. It’s for all intents and purposes been the only one on offer in much of our public policy debates on these issues. But other approaches are possible. After ceding a decade-long monopoly on this debate to progressives and their preferred policy prescriptions, conservatives in Alberta are offering a coherent strategy and alternative framework to address these issues—one that other like-minded national and provincial leaders searching for solutions can build upon.

I offer no prediction on whether the Alberta approach will work. Experts who make predictions are wrong as often as they are right. But it certainly seems like a bright spot on the Canadian horizon to see governments testing out starkly contrasting policies.