Eighty years ago today, the Allies invaded Sicily, defended by Italian and German troops. In the invasion force were the 1st Canadian Division and the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade, some 20,000 soldiers ready for their first full-scale operation after three years in England.

The Canadians reached Sicily in two convoys, one of which had three ships sunk by U-boat torpedoes, and lost 58 soldiers, forty of the division’s 25-pounder artillery pieces, 500 trucks, the headquarters’ wireless equipment, and Major-General Guy Simonds’ baggage. The division’s chief engineer, Geoffrey Walsh, remembered that he had to loan socks to the 1st’s commander.

The invasion proceeded well nonetheless. The Canadians and British troops, under General Bernard Montgomery’s 8th Army, landed on the southeastern shore, the Americans to the west. There was light opposition on the beach, with Italian troops surrendering quickly in the face of overwhelming force—“They hadn’t got their heart in it at all,” one soldier said. The Canadians moved inland over rugged terrain with steep hills and winding narrow roads, and the constant heat, dust, and malaria-carrying mosquitoes soon began to wear down the men. After three days, Montgomery recognized that the Canadians, not yet inured to the climate, needed a few days rest. Supplies came forward, carried by “liberated” mules.

Moving forward on July 15, the leading units bumped into the Germans, a small blocking force from the Hermann Goering Division. The Wehrmacht had better machine guns, well-trained mortar men, and deadly 88mm guns that pierced the lightly armoured Sherman tanks, and in this first engagement the Canadians suffered 27 casualties. The next day at Piazza Armerina, a town best known for wonderful Roman mosaics, Panzer Grenadiers blocked the advance for a day until the Loyal Edmonton Regiment took the town. At Valguarnera, the enemy in battalion strength fought stubbornly, and it took two brigades—and 145 casualties—to drive them back. But the Germans had noticed; Field Marshal Albert Kesselring reported to Berlin that his Grenadiers called their opponents “‘Mountain Boys’ [who] probably belong to the 1st Canadian Division.”

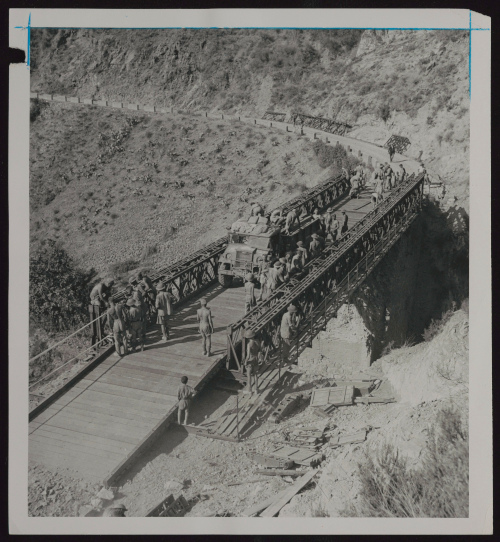

For the next two weeks, the 1st Division fought over the steep hills and through the deep ravines of central Sicily. It seemed that every turn in the winding roads had a German machine gunner or two, each blown bridge a defended obstacle to be overcome, each small town a platoon of Germans to inflict casualties and another delay. So too did dysentery, diarrhea, and malaria in the towns that Brigadier Bruce Matthews, the division’s artillery commander, called “filthy & smelly beyond description.” At Assoro, the Germans held the high ground and prepared to fight. There the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment swung wide, found a higher peak, and scaled it at night. The dawn revealed the Germans eating breakfast, and the Canadians poured their fire into them. Well-trained, the enemy recovered quickly, even the cooks fighting back, and their artillery pounded the Canadians. Soon counterattacks began, and the Hasty Pees were hard-pressed but hung on. The German defence of Assoro had been completely disrupted.

At nearby Leonforte, the 2nd Brigade’s Loyal Edmonton Regiment fought into the town, but the Germans counterattacked in force and cut off the Eddies. Brigadier Chris Vokes organized a flying column of tanks, anti-tank guns, and infantry to bust into Leonforte, free the Edmontons, and, after heavy fighting, finally liberate the town. Two days of battle had cost the 1st Division 275 casualties.

At Agira, 25 kilometres to the southeast, the Germans were again ready in strength. Simonds unwisely sent one battalion after another into the attack; each assault crumbled under the mortar and machine gun fire, and the Three Rivers Regiment lost ten tanks to the 88mm guns. Simonds persisted, using a heavy artillery barrage and tanks to support the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry in taking their first objective. The Germans promptly recovered and drove off subsequent assaults. But when a company of Seaforth Highlanders climbed a 100-metre ridge that dominated their position, and when the Loyal Eddies took another ridge west of Agira, the Germans had to retreat. Again the cost was heavy, but this was a major victory.

The Sicilian campaign was nearing its end. The Americans under General George Patton had stormed through the western island, freed Palermo, and were moving east quickly. The British had advanced in parallel with the Canadians, and in Rome the Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini had been toppled. Only northeast Sicily remained in German hands.

For the Canadians, only one major attack remained. In the level valley of the Simeto River Simonds created a striking force consisting of an armoured regiment, a reconnaissance squadron, an infantry battalion, a battery of self-propelled artillery, and anti-tank guns. The Three Rivers and the Seaforths commanders coordinated their plans, the infantry and tanks “married up” company for company, and the two COs, riding in the same tank, led their troops into action on August 5. The Germans’ 3rd Parachute Regiment, taken by surprise, fought to the last man against the dismounted infantry and the Shermans, but the attack succeeded with cannon and machine gun fire. The Seaforths had lost 43 men in a battle that demonstrated that army and infantry cooperation worked and could be mastered. General Simonds had learned something too.

Kesselring and the German high command sensibly accepted that Sicily had been lost and, on August 10, one month after the invasion, began a superbly executed withdrawal to the Italian mainland. They had put four divisions into Sicily’s defence and lost 11,600 soldiers. The Allies had suffered 19,000 killed, wounded, and captured from the dozen divisions they employed. It was a victory, but a costly one.

The 1st Canadian Division and the 1st Armoured Brigade had proven themselves in battle, but they too had paid a steep price: 562 killed, 1,664 wounded, and 84 taken prisoner. They had learned it was no easy task to fight the Wehrmacht. The task now for the Canadian troops and their Allies was to carry the war to the mainland, to an Italy now under the complete control of the Nazis. The bloody war would continue.