The following is the latest installment of The Hub’s new series The Business of Government, hosted by award-winning journalist and best-selling author Amanda Lang about how government works and, more importantly, why it sometimes doesn’t work. In this five-part series, Lang conducts in-depth interviews with experts and former policymakers and puts it all in perspective for the average Canadian.

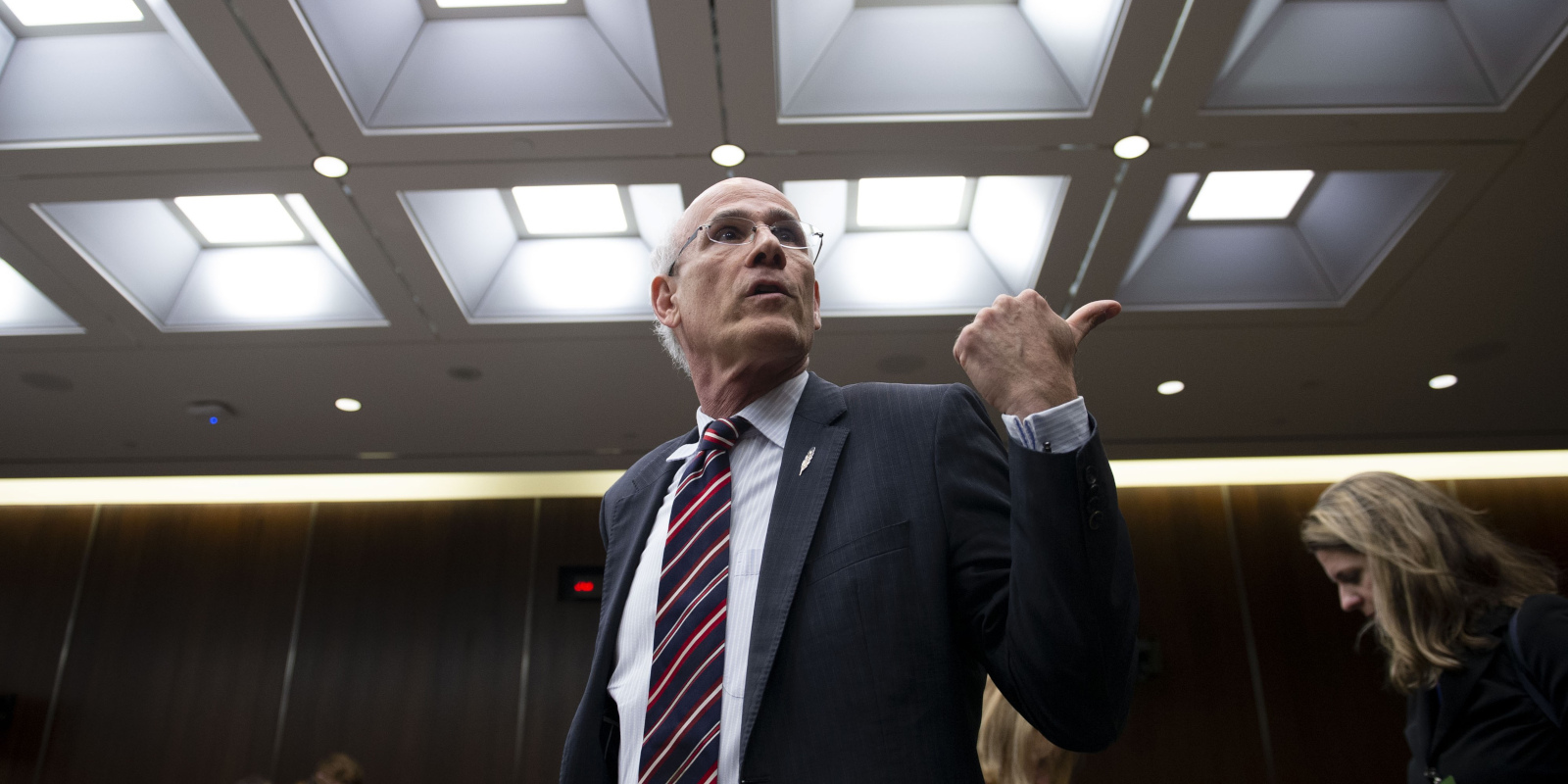

This episode’s featured guest is Michael Wernick, a former clerk of the privy council and secretary to the cabinet of Canada with decades of experience working in Canada’s civil service. The two discuss Canada’s civil service, how the public sector and the political arena interact, and what, if anything, can be done to improve the performance of our government bureaucracy.

Read Amanda’s accompanying column on this topic here.

You can listen to this episode of Hub Dialogues on Acast, Amazon, Apple, Google, Spotify, and YouTube. The episodes are generously supported by The Ira Gluskin And Maxine Granovsky Gluskin Charitable Foundation and The Linda Frum & Howard Sokolowski Charitable Foundation.

AMANDA LANG: Michael, thanks for being with us.

MICHAEL WERNICK: Thank you.

AMANDA LANG: So, Michael, I want to start with this suspicion, I think you could call it, that people have that the quality of our civil service is different than it used to be; that it’s deteriorated over time. Can we start there? Do we have less talent, less expertise inside the civil service than 20 or 30 years ago?

MICHAEL WERNICK: No, I don’t think there’s any evidence for that. Maybe a bit of nostalgia from people that left and think things were better in their day. But the evidence is that in a more and more demanding environment, the public sector—federal, provincial, and municipal—continues to deliver for Canadians.

AMANDA LANG: So when you say “continues to deliver”, how do we measure that? How would you, both formally in your role but across your roles in government, say this is effective and it’s working?

MICHAEL WERNICK: Well, what governments try to do hasn’t really changed that much. It’s about keeping us safe and secure and generating economic growth and prosperity. There are distributive issues, there’s how to engage in the world. And by almost a long list of measures, Canada is a successful country. So peace, order, and good government must have something to do with that. Public sector itself does try to identify measurements that it can present to Parliament with the spending estimates. These are goals and objectives, and targets, and there’s an incredible infrastructure of feedback loops in the public sector to check up on how it’s doing, from internal audits to almost a dozen officers and agents of Parliament. So there’s this continuous checking in and looking back on what could have been done differently.

AMANDA LANG: So, it sounds like, obviously, there will be robust procedures in place and, as you say, ways to check and review. If anything, what we hear is there may be too much of that; that there may be too many layers making sure that this will stand up to tests down the road. Do you see any evidence of that? That we have maybe too many—I don’t want to say bloated asthese have become such loaded terms, but you do get the sense from people who’ve been inside government that there is a lot of bureaucracy in the bureaucracy.

MICHAEL WERNICK: Well, it’s an interaction with democratic politics because a lot of it is a political response. Something happens, and the instinctive of ministers is to add rules and constraints or to add oversight bodies. And that’s perfectly understandable. We tend to add and add and add—and it’s much more difficult to strip them away and delayer some of that. The oversight is a good thing, I don’t want to be misunderstood. It helps people learn and adapt, and do better in the future. But there’s this kind of axis that works between all of the feedback loops and their institutional media coverage, which tends to focus on the problems, opposition politics, and so on. And there is a risk, in which we see a chill; people get risk-averse. They don’t want to get into trouble. That applies to ministers, it applies to public servants. They become cautious and incrementalists. And that’s clearly a problem with large organizations of any kind.

AMANDA LANG: That’s very true. In the private sector, we certainly have evidence of that, where there’s maybe a disconnect a little bit between your activities and the end goal. The bigger the distance, the less responsiveness you can get. Is there a way to solve that? One of the reasons I want to talk to you is we should appreciate how complex an apparatus like our government is, and even a single department of government is like a good-sized company. And so I don’t want to diminish that in any way. Are there ways that we could take out some of those impediments to more direct and effective behaviours?

MICHAEL WERNICK: Let me start with the framing. The public sector is federal, provincial, municipal, and Indigenous. And almost anything meaningful involves interaction of those governments, whether it was climate change or responding to the pandemic, or whatever. So a lot of it is about multi-layered government. The federal government is actually about 300 different organizations and about 70 different occupational groups. So it is more like a very, very diverse holding, trying to do all kinds of different things. And the differences of managing a prison system, or border services, or a policy department, or a regulator are almost like the differences between managing in different industries in the private sector. Of course, there are some common elements, but the business of government is really, really diverse in its nature. Almost no sentence about the government or the public service will hold up to closer scrutiny. You almost have to look at specific organizations. There are pockets of excellence and innovation. There are organizations that run into trouble. What I’d say is a common element is do you have that learning software where you can take in new information, you can learn from mistakes, and you can commit energy and resources to doing better? That applies to the whole system. It might apply to a specific department.

AMANDA LANG: So let’s drill down on that a little bit, because I think it’s an important point to remember that this isn’t one behemoth, and to your point, it’s actually multiple organizations inside an organization, interacting with other organizations, or other levels of government. So complexity upon complexity. In your tenure, did you see departments that really got that right, that managed a culture of innovation, a learning environment, that really did strive for excellence? And what were the qualities of those departments?

MICHAEL WERNICK: I think there are lots of stories. They don’t tend to get as much attention as the ones that run into trouble. That’s understandable. And so one of the things I tried to do in my reports to the prime minister on the public service is tell some of those hidden and plain-sight stories. The evidence is there that the kinds of services that are delivered to Canadians, particularly transactional services, are completely different than they were even ten years ago. So people adapted to the internet; they moved services to the web; they added social media. Now they’re dealing with Zoom and teams for getting work done. About 85 percent of Canadians’ transactional relationship with the government of Canada is now online. It’s on websites and apps. And we’re now having a discussion about artificial intelligence and GPT. So there’s always a wave of innovation. I just saw a story posted this week about how Statistics Canada has adapted to cloud computing. It’s not a sexy news story, but it’s an important work by Statistics Canada.

AMANDA LANG: Yeah, so for every one of those, unfortunately, I think we could point to Canada Revenue Agency and the fact that it’s not automated, and that we have these—

MICHAEL WERNICK: But there’s a well-known phenomenon that you can make a graph look steeper or flatter depending on the timescale you use. And if you think about the way CRA worked ten or 15 years ago, it has moved to MyAccount, it has moved to personalization, it has moved to uploading of your tax documents proactively. So we’re in the next wave of service improvement. And I think it’s sometimes difficult to see the perspective. You can renew a driver’s license in seconds; now you can pay online; your money comes in through direct deposit. You don’t have to go very far back where none of these things were true.

AMANDA LANG: Yeah. I like looking on the right side of this because, to your point, it rarely happens that people actually take a really un-jaundiced view of how things are functioning. So then let me challenge you a little bit to say, “What would you say isn’t working well?” If we’re doing pretty well, and as you say, peace, order, good government—we seem to have all of that—where could we improve? Where’s what we would call opportunity in a 360 review?

MICHAEL WERNICK: Well, it is not hard to get ministers and governments to pay attention to transactional services that Canadians interact with. So if there’s a problem with passports or immigration processing, or EI, it will get fixed. People will invest the money and resources. One of my themes is what gets neglected and rusted out almost literally are all of the internal services: finance, human resources, information management, material management, buildings, tools. These are the kinds of things that make everything else possible. Not only do they tend to get neglected until there’s a crisis, but when you have one of these waves of spending reviews and cuts, they tend to be the things that are cut because any group of politicians will go out and say, “No, no, we’re protecting service to Canadians. We’re going to find efficiencies within government.” And of course, it’s all of these internal services that get cut back and particularly training and leadership development, which the public sector needs to invest a lot more in to keep up.

AMANDA LANG: One thing we’ve heard is just on that front that the top civil servants, the deputy ministers, but also the associates and assistant deputy ministers tend to get moved around. And that can be a bit of an impediment to building up their subject matter expertise, if you will; that their own career development suggests they should be moved, but from a minister’s point of view, they lose some of that institutional knowledge too frequently. Would you say that’s a fair concern?

MICHAEL WERNICK: It’s never easy to get the balance right. I mean, I dealt with this problem as clerk and had to move people around. And it happens because vacancies are created. People retire, they get sick, they take jobs elsewhere, and you have to find somebody to fill that job. If you move somebody within the public service leadership, you just get another problem, and so on. So bringing in people from outside, from provincial governments and other sectors, can help with the supply. But I would say in the senior leadership, you are not always looking for that deep specialist in one area; hybrids are very, very useful. Somebody in policy who has worked in operations; somebody in operations who knows what it’s like to work at the finance department of the Treasury Board; people that have worked in regions coming to headquarters, and so on. So I think the people that are most successful in leading complex public sector organizations have a composite of skills. And you shouldn’t just look at their current job. You should look at the last three or four jobs that they did before.

AMANDA LANG: So one of the key pieces of that and of a really well-functioning department is that interaction between the political and the bureaucracy, the civil service. How does that work? Is it working well? Are we getting the best out of those relationships?

MICHAEL WERNICK: I wrote an entire book about this if people want to dig into it deeper. There’s a natural tension in it. And when it works well, it’s magic because you need political leadership to change things. So the pair bonds between ministers and departments keep changing as well. There’s been a complete turnover of the cabinet that I worked with only six or seven years ago. So the churn happens on both sides.

AMANDA LANG: I guess we can touch on the fact that you also were quite involved in the ways that the politics of a thing can interfere with the policy of a thing. Perhaps unpleasantly, in some cases. Is that well-managed? And I say that from the point of view, really, leaving aside political stories, of the bureaucracy trying to get things done, having a view about the longer-term progress towards something and being, I don’t want to say thwarted, Michael, but it being interrupted by some political realities of the day.

MICHAEL WERNICK: It’s more complex than that. Sometimes you get forward-looking ministers who have an eye to leaving a legacy and doing things that they won’t be around to see the full fruit of. And governments do a lot of that. They make investments in infrastructure, and they make investments in learning programs. I could go on. But they also have to survive the day-to-day combat of partisan politics and get elected. So they always have that in their mind, and it can make them risk-averse on some issues. But that’s democratic politics, and I’m glad we live in a democracy.

AMANDA LANG: I know that you have a view about this notion of the right size of government. There’s some data on sweet spots around what you’re investing and what you get out, and maybe that’s one lens on it, perhaps. But have you ever worried that—we’ve certainly seen a rash of hiring through pandemic and post-pandemic that is public sector hiring, there’s no doubt about that. Do you ever worry that there is such a thing as too big when it comes to the size of our public sector?

MICHAEL WERNICK: Well, I mean, that’s a decision for democratically elected politicians to make, largely through elections. How much do they want the government to do, and how much are they willing to generate in revenues to pay for it? About every ten years or so, there’s a major reset. Jean Chretien had a program review. Stephen Harper had a deficit reduction action plan. These exercises of culling and weeding and detaching the public sector are a good idea, but they come down to political choices about this is important to keep and this we can stop doing. So if we’re going to do it again, I think the politicians have to be clear about their stop-doing list.

AMANDA LANG: Do you have a view about whether that’s been done well in the past, or does it tend to be a blunt instrument? When it’s cost-cutting, that’s the aim, rather than—you don’t get the impression that there’s a very incisive review by department of what tends to be, I think, a bigger picture of “We just need to cut, so let’s go find it”?

MICHAEL WERNICK: No, I think that’s another phenomenon. It just doesn’t make the news. We went through the program review. We went through strategic reviews, administrative service reviews, reviews of legal services, and the deficit reduction exercise by Steven Harper. There’s a constant feedback loop on that. And it’s something evidently Canada does well. Just look at the pictures in France, where you’ve got social turmoil over small changes in pension schemes. We fixed our public pension plans twice, and we’ve gone through all kinds of major structural reforms in Canada without that kind of turmoil. In the program review that Jean Chretien and Paul Martin did, we went from a deficit that was about six percent of GDP to balance and surplus within four years. I don’t think there’s another country in the G7 that could pull that off.

AMANDA LANG: It was impressive. And provinces would say it came at a cost to other governments, I think.

MICHAEL WERNICK: Sure. But they have their answerability to their voters as well.

AMANDA LANG: Yep.

MICHAEL WERNICK: Any provincial premier is free to raise income tax or sales tax, or corporate tax and make up the difference.

MICHAEL WERNICK: Do you worry that that focus on fiscal balance is missing these days? Does that concern you?

MICHAEL WERNICK: That’s a political—that’s for the 2025 election, if people want a government that’s running small surpluses, they should vote for one. I don’t think it really matters whether that government is running at 15 percent of GDP or 13 percent of GDP. We have to make decisions on what’s important to Canadians, whether it’s health transfers or bulking up defence spending for a more dangerous world, or better infrastructure in our cities. Politics is about choosing.

AMANDA LANG: One subject that has gotten a fair amount of attention lately has been the size and quantity of consulting contracts. And I know you’ve written about this. You’ve obviously had lots of time to be involved in these kinds of thinking around these things. Is it worrisome that we seem to be outsourcing knowledge and decisions in this way, if I can put it that way?

MICHAEL WERNICK: Well, as I told the Parliamentary Committee, I’ve never seen management consultant firms play a role in policy. I’ve seen lobbyists, I’ve seen special interest groups play a role in policy, but never management consultants. They basically are in the area of service delivery operations and transactional kinds of things. They bring expertise from working with private sector clients in the financial sector or telecom or services or tech. Technology is changing so quickly. We could talk about the arrival of cloud computing and social media and AI. The idea that the public service could keep up all by itself is just indefensible. You need to bring in outside perspective and expertise. Some of the antidote to that mentality of, “Well, this is the way we always do things,” is to find out how it’s done elsewhere. So I think, well used, they can play a very positive role in keeping the learning software going. If people are worried about a dependency on outside firms, then my answer would be, “What are you going to do about it?” And I would double the investment in training and leadership development so the capacity in-house is made stronger.

AMANDA LANG: One thing that I have heard is that there’s a reliance on outside management, outside views, consultants, to reassure, if you will, that there’s a lack of confidence inside departments that they have the information. I don’t know whether that’s a political lack of confidence or a bureaucratic one, but does that resonate with you at all? Does that have any truth?

MICHAEL WERNICK: Yeah, no, I said that in my article. It cascades down that Treasury Board ministers and specific ministers often are a little skeptical of public service advice, especially about costing and about implementation, they do seek reassurance from a good housekeeping seal, to use an old metaphor. And that’s a common reflex by ministers. And I don’t think ministers should be expected to depend 100 percent on public service advice about these things. But it cascades through into the public service leadership as well. But it’s good practice to use outside auditors. It’s good practice to bring in external legal consultants to check on the advice that’s been given so they can play a complementary role to internal capacity that can actually be helpful.

AMANDA LANG: I guess what seems surprising to many is that the sheer dollar volume of consulting contracts rose as the bureaucracy swelled as well. In other words, we have more people on staff, and we’re also outsourcing some of this work.

MICHAEL WERNICK: Well, as I told the committee, it’s not a zero-sum, it’s not a teeter-totter. It just means there’s more work. There are more projects at a larger volume, at a faster pace with shorter deadlines. So there’s more work for everybody, more work for public servants, and more work for external contractors. If you want to slow it down, then you have to slow down the pace of work and make decisions about, “Well, this is no longer urgent, or we’re not going to do this anymore.” Those are hard decisions to make.

AMANDA LANG: They are. I’m curious for your view on that relationship between the political side, so the minister, if you will, and the civil service. I mean, you alluded to this, that there can be sometimes a little bit of, you didn’t say tension, but I’m going to say tension between the two. Is that relationship working for the most part as it should, or is there something we could do to improve it?

MICHAEL WERNICK: I think it generally works quite well. And again, the evidence is things get done, and this is a successful country, and it is an open, transparent, democratic country that ranks very highly in all the governance measurements around the world. So evidently, something is working. You can end up with pair bonds where you have a difficult relationship. I talk about this in my book. Sometimes it’s the minister, the chief of staff, sometimes it’s the senior official. And it’s really important at the top level the 80 or so senior leaders at the top of a pyramid of over 300,000 people are the ones that spend the most time with ministers. Having a good, trusting working relationship is essential.

AMANDA LANG: One of the suspicions I think you’d find most of your fellow Canadians harbour is that there is bloat inside departments that, if we could get it, just get in there and simplify, and that there’d be tons of cost cuts available. Are you here to say that that work does get done and what’s available does get cut? Or do you think there is still some room in there for more leanness or efficiency?

MICHAEL WERNICK: It’s always worth trying to do better and be leaner, and sometimes a broad spending review will help. The hardest argument to make, though, is we need to make an investment to do better. We need to replace the IT system, and it’s going to cost you before you see the return, right? That’s a very difficult argument to get approval for. And so if you want to go at that, you also have to be prepared to make investments in training in new technology following up. The best private sector practice is you spend money on tools and technology, and training. And I’d like the public sector to do that as well.

AMANDA LANG: There is a perception even when some of those investments are made, and Phoenix is the one that comes to mind, it’s the famous one, but there’s this perception that we don’t do a good job, whether that’s implementing big projects, whether that’s procurement over time. Again, how do you reframe that for us, if you want to? Is there another way to see those things?

MICHAEL WERNICK: There’s no way to defend the specific incidents, but IT project failures are rampant in the private sector as well. It is a tough thing to do and to do well, and I could finger-point to other examples in the private sector. The risk tolerances in the cybersecurity risks associated with the public sector make it doubly hard in some ways. So clearly, just have to keep working on new technologies, whether it’s Zoom-based work platforms or what artificial intelligence is going to do to some of the service delivery, and so on. If I can go back to—it’s worth trying to make the operations of government leaner, but you’re not going to balance the budget on that. Overwhelmingly, what the $400 billion the federal government will spend this year will go to our transfers to provinces and transfers to individuals. There are six big programs that account for about two-thirds of the dollars. So you could cut the public service in half, you would save $20 billion. It’s not going, so it’s worth doing because better outcomes and better services and better policies are the result, but it’s not going to be the key to fiscal balance.

AMANDA LANG: That’s a fair point, that it’s not the big budget item. And maybe we shouldn’t pick on it. You’ve alluded to the fact that our government functions well relative to others. Are there countries that you would look at and compare us to and say, “We should emulate?” Are there any other countries out there or functioning governments that you think get something better than we do?

MICHAEL WERNICK: There are always examples to learn from, and I participate in a lot of international fora, but I get tired of hearing about Singapore and Estonia because, like Estonia, is 1 million people in an area smaller than Metro Toronto. So we are a big country of 40 million people spread across six time zones, and we are a federation in which we have multiple layers of government. So there’s a limit to how much you can take from England or Finland or Germany, but it’s always worth trying.

AMANDA LANG: And of course, the other piece of this that maybe you don’t think there’s any issue, but I guess my question would be if there’s more, we should be doing on attracting and retaining the best and brightest? And I guess maybe it is rose-coloured glasses, Michael, it’s possible. I mean, I was a child in the 1970s. It felt as though maybe the quality was the same, but the respect people had for our civil servants was phenomenally higher. I don’t think that’s in any dispute. They were just among the most respected practitioners out there. And that has changed. And I can’t help but wonder if that doesn’t actually have that kind of vicious cycle effect where then you don’t attract the same calibre of people. It may be also true in the political realm.

MICHAEL WERNICK: I mean, the evidence is I never had trouble attracting good talent. And there were people from law firms and private sector firms and universities willing to come in and spend some time in government. They may not want to devote their entire career to it. I’m an advocate of more interchange. It’s a good idea to have people crossing from the public and not-for-profit sectors for a period of time and learning about what it’s like on the other side. We only do handfuls of that a year. We should be doing probably 100 to 200 interchanges every year. And then people go back to their private sector careers or they do their government job with a lot more awareness of the rest of Canada.

AMANDA LANG: When you do get those successes, especially people who are bringing special knowledge, special experience, there’s this perception, and again, we can find pockets in the private sector, so maybe it’s not fair to pick on government. But it’s a super important service for all of us, so I’m going to pick on it a little bit. There is this impression that the big ideas, the fast-moving people get slowed down, that there’s a weight to the system that stops things from happening the way they might, as fast as they might, or at all. Any truth to that?

MICHAEL WERNICK: Well, you work in an environment with very different risk tolerances, as I talked about. So definitely. And you work in a place where authority and decision-making is far more distributed than it would be on the top floor of a corporate office tower, where you can walk around to five people and get a decision. And there’s this feedback layer. So managing at the top levels of the public sector is far more difficult. And so my experience is that that’s the challenge, and that’s the reward. And being an innovator and a reformer in the public sector is a very rewarding career.

AMANDA LANG: One of the things we spend less time on in general is thinking about innovation in services. Though companies do it, of course, by way of their own business models. Do we innovate enough in the delivery of government services? Is that a constant process as well internally?

MICHAEL WERNICK: Well, I mean, there were no iPhones in 2007, and now people do all kinds of things on apps. So evidently, a lot of transactional services have migrated to the internet, to interactive websites, to phone apps, and so on. And that will continue as AI-driven chatbots become front-line services and so on, blockchain will affect payment systems, and so on. So there’ll be a constant wave. I don’t think the public sector can ever be the first mover because of that risk tolerance. An IT failure in government is something that can end the career of a minister or a senior official, so the art in it is spotting things that are happening in the private sector and the technology world and saying, “Okay. Now, how can I apply this to the business of the service that I’m managing?” And that’s a constant effort by the public sector.

AMANDA LANG: Starting from the position that you think things are pretty good because I don’t want to make this next question sound like I haven’t been listening. I think you think that our government functions pretty well and the bureaucracy works. What would you put on a list of things that would improve it?

MICHAEL WERNICK: I don’t want to be misunderstood. There are lots of things to attend to. Information management within the government is a shambles. And I told the parliamentary committee that, very directly. The public sector does not invest enough in training and leadership development. And I told the parliamentary committee that directly. There are obviously areas of service that need to be fixed and corrected when problems are detected. I’m not making the argument that government is perfect. I’m making the argument that it learns and adapts, and moves forward, and more attention to how it works, especially how it works internally, is very, very welcome. I’m glad you’re doing this series. It is so important to the security and prosperity of Canadians that we should pay more attention to how the public sector works.

AMANDA LANG: And also, occasionally admit that it’s getting it right?

MICHAEL WERNICK: Well, I get more irritable with all the commentary, which trash talks the country as if we’re some failing Stalinist gulag when all of the evidence is we’re one of the most successful societies and countries in the world both in terms of prosperity and quality of life, and inclusion. There’s a whole other theme we could talk about, about that nostalgic public service of the 1970s and ’80s was run by white males. And there’s been an arc of inclusion to bring women into leadership roles. The public service I joined, you could lose your security clearance for being gay. And that’s the language of the time. A lot of effort to catch up to the diversity of a country where a quarter of Canadians were born outside this country. I could go on. The public service now is 55 percent female, and half of the leadership ranks are female. I don’t think we want to go back to some nostalgic time of old white men sitting around.

AMANDA LANG: Michael, some of the time it feels as though people think you could just get rid of government. It’s not playing this particularly useful role, or it’s an encumbrance, if anything else, to this hardworking private sector that wants to get things done. What’s the reality in your view of that?

MICHAEL WERNICK: Well, the reality is that private and public sectors are completely codependent. I mean, there would be no public sector if there was no growth, and income, and wealth to tax to pay for things. The lesser-known part of it is how much of private sector growth and innovation comes from government. There are some obvious parts to this that we tend to only think about from time to time. The Coast Guard and Border Services, and the Seaway Authorities make commerce possible for a trading nation; it’s $250 billion a year through our ports, $3 billion a day across the Canada-U.S. border, as we learned during the pandemic. The government procurement is important to the demand and the prosperity of all kinds of businesses across Canada. I think the least known one is how much innovation came out of the public sector. Either government research labs or government research grants. The entire consumer electronics industry came from alkaline batteries, which were just invented at the University of Toronto.

Everything on a smartphone came from the public sector: The internet protocol, the HTML code, the wireless protocol, touch screens. Siri started with a government grant. The Google search engine started with the National Science Foundation grant. There would be no Apple, no Google or Tesla without the seed money and the risk-taking by the public sector. The entire fracking industry came from U.S. Energy Department grants. The pharmaceutical industry comes from medical research grants and university research. The grains and oil seeds industry comes from experimental farms and government research, and so on. There’d be no biotech. I can go on and on. So I think it’s better to think about the interconnection and the codependency that, for Canadians, when you have a strong public sector, you get a strong private sector, and vice versa. And it is something that Canada does better than many other countries.

AMANDA LANG: I think it’s such an important point to remember they get the net benefit of having a government that’s functioning well and plays these important roles. I guess, the pushback would be procurement’s an interesting one, you actually often hear—and maybe it’s our tendency to focus on those negative stories—and by our tendency, I mean journalists’ tendency, perhaps—you hear about companies that can’t sell to government, that government is too risk-averse, that their procurement policies don’t favour new products, these kinds of things. Do you think those are at the margin? Do you think, for the most part, just the importance of that purchasing power outweighs any of those complaints?

MICHAEL WERNICK: Well, I mean, the complaints are probably coming from unsuccessful bidders, which sounds a bit unkind. I mean, procurement is a very complicated process, but it’s carrying all kinds of objectives, and value for money is only one. Politicians have loaded it up with regional development and supporting small business and promoting Canadian champion companies and tracking greenhouse gas emission targets, and supporting equity-seeking groups to build businesses. I can go on and on. There are a lot of layers to procurement policy, and because we’re an open trading nation, it has to comply with our trade agreements with our partners. So it is difficult to make procurement processes work fast. The ones that get attention are the big dramatic, once in a while we buy 88 fighter jets. But there’s a lot of routine public service procurement that works very well and just isn’t really newsworthy.

AMANDA LANG: I think most people would agree that, at least optically, when we do buy fighter jets, we don’t do a good job of it. It takes too long, and it costs more than we thought. And we see a bunch of reversals of decisions. Is that a political problem or a bureaucratic one?

MICHAEL WERNICK: Bit of both. I’m not aware of any country that really is happy with its defence procurement system. The Americans aren’t, the Brits aren’t, the French aren’t, so it is a particular challenge. It’s a topic for another day: whether defence procurement could be made to work better.

AMANDA LANG: Overall, though, the only other complaint you would hear is sometimes government is taking up, of course, or crowding out, capital from other parts of the market. In other words, if government wasn’t doing it, the private sector would do it. That’s not true of some things. Literally, only the government could do some functions. But is there an argument to be made there that when our government does get bigger in our economy, it is actually at the cost of the private sector?

MICHAEL WERNICK: Not at a macroeconomic level. There’s no evidence shortage of capital for the private sector. And public sector often fills in risk zones that the private sector lenders are not willing to take. I mean, that’s why we have a variety of government credit institutions like BDC and ECC and the farm credit, and so on, because the market isn’t fully living in that space.

AMANDA LANG: I guess the bottom line is the message that you might share is that we should remember the benefits, the codependency, I guess, in a very positive way, both public and private sector. They are not two solitudes.

MICHAEL WERNICK: I mean, the key point is the boundaries between what government does and what the private and not-for-profit sectors do—and let’s not forget the 80,000 Canadian charities and not-for-profits is a matter for democratic politics to settle—ee can pick people that would prefer things to be outsourced or privatized, and we pick people that prefer they’d be delivered directly by government. That’s a choice we can make in a couple of years.

AMANDA LANG: So good to have you. Thank you so much for this.

MICHAEL WERNICK: Well, thank you for your interest. I think, as I said, peace, order, and good governments are in the interest of all Canadians.

AMANDA LANG: Indeed, thanks.

Recommended for You

Ginny Roth: J.D. Vance, Pierre Poilievre, and how they slice their economic pie

David Polansky: As President Biden leaves the race, will the Democratic Party hodgepodge hold?

RCMP spending to protect MPs may have risen 112% since 2018, as Canadian politicians face greater rise in threats

Trevor Tombe: Canadians are paying billions in hidden taxes on new homes