This week’s Fall Economic Statement is expected to show that this year’s deficit will be higher than the $40 billion that was projected in the March 2023 budget. It may in fact be as high as $56 billion (or 2 percent of GDP) according to one estimate which would be nearly as large as the deficits that were recorded during the 2008-09 global financial crisis in both absolute and relative terms. It also means that Ottawa’s fiscal trajectory is moving in the wrong direction after running a $35.3 billion deficit (or 1.3 percent of GDP) last year.

This budgetary deterioration raises a bigger question about whether the Trudeau government has manufactured a structural deficit that won’t be resolved merely by a combination of rising revenues and some spending constraints. It will now require more concerted (and possibly draconian) efforts to bring Ottawa’s revenues and outlays back into balance. The budget, in short, won’t balance itself as the prime minister infamously put it.

I’ve come to think of the problem in the following terms: federal fiscal policy since 2015—but particularly since the pandemic—has come to reflect Stephen Harper’s tax rates and Justin Trudeau’s spending preferences—and the two are ultimately irreconcilable. Something has to give.

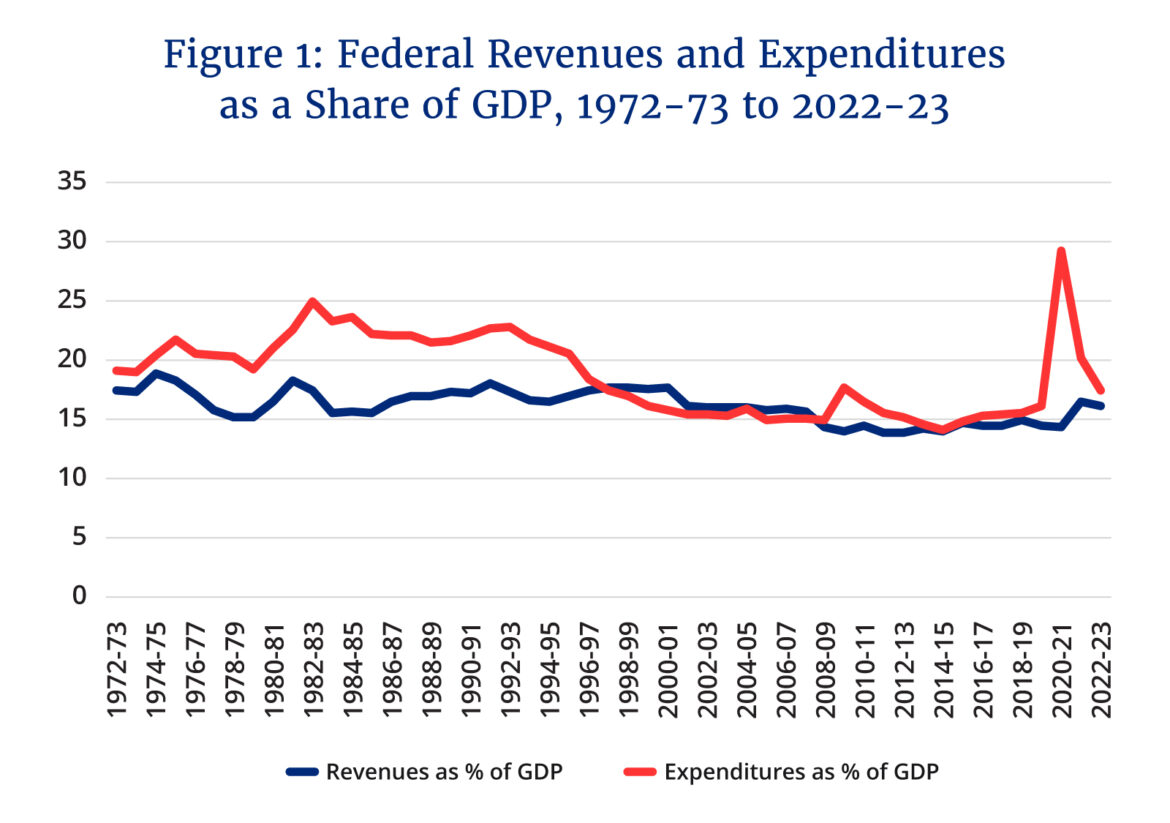

Figure 1 plots federal revenues and expenditures as a share of GDP over the past fifty years. It conveys a somewhat complicated story. Revenues have bounced around a bit but remained largely stable. Expenditures have changed more significantly in response to major developments such as economic downturns or the COVID-19 pandemic. Annual revenues have averaged 16.1 percent of GDP over this period. Expenditures have averaged 18.8 percent.

Over this half century, expenditures have therefore averaged 2.71 percentage points more than revenues. The gap hasn’t stayed constant of course. It has increased and decreased based on different factors including economic trends and fiscal policy choices. But just over three-quarters of the years during this 50-year period have witnessed expenditures exceed revenues as a share of GDP.

The Chrétien-Martin governments came to office in 1993 with a gap of more than five percentage points. As a result of the Program Review exercise in 1995, they subsequently oversaw eight consecutive years of budgetary surpluses in which revenues exceeded expenditures. Overall, this period was marked by an average gap between expenditures and revenues of just 0.75 percentage points as a share of GDP.

The Harper government’s fiscal policy followed a different trajectory during its three terms in office: its first term was marked by large-scale tax reductions, its second term involved fiscal stimulus in response to the global financial crisis, and its third term was an exercise in fiscal consolidation to eliminate the deficit produced during the worldwide recession. The net result was that expenditures exceeded revenues by an average of 0.72 percentage points between 2005-06 and 2014-15.

The main story, however, from the Harper government’s fiscal policy was in hindsight its tax reductions (such as lowering the HST/GST by two percentage points) which lowered federal revenues as a share of GDP from about 16 percent to 14 percent. One must go back to the early 1960s to find comparable levels of taxation. In this sense, the Harper government’s ability to bring revenues and outlays into approximate balance in the aftermath of the global financial crisis is an even more notable accomplishment because revenues were about two percentage points lower than their average over the past fifty years.

The Trudeau government was elected with a short-term plan to solve for the federal government’s revenue-expenditure gap: borrowing. Its 2015 policy platform envisioned three years of annual deficits averaging $10 billion per year. Although the government predictably failed to live up to this promise and ended up running larger and longer deficits, its fiscal policy in the pre-COVID years saw expenditures exceed revenues by an annual average of 0.84 percentage points. This was broadly consistent with the overall performance of the Chrétien and Harper years.

The gap, however, reached an unprecedented level during the COVID-19 pandemic. It averaged 9.25 percentage points during the two-year pandemic and has remained elevated ever since. March’s budget projected it to be 1.4 percentage points this year. Tuesday’s Fall Economic Statement is bound to increase that upwards. It may be below the fifty-year average (though the Trudeau government’s fiscal record, including the pandemic, has produced an overall gap between expenditures and revenues that exceeds the historic average by about 0.25 percentage points), but it’s self-evidently trending in the wrong direction.

What’s the takeaway? As long as we’re living in a world of Stephen Harper’s tax rates and Justin Trudeau’s spending preferences, the gap is likely to grow—especially in the face of various spending pressures such as calls for higher spending on climate change and national defence and the inexorable rise of old-age spending.

We’re going to have to have a reckoning: are we prepared to pay for the size of government that we want (and some people argue that we need), or are we ready to reset our expectations about the size of government to bring it in line with the rate of taxation that we’re prepared to pay?

There’s little reason to believe that Tuesday’s Fall Economic Statement will answer this question. The Trudeau government’s weak political position increases the likelihood that the gap between revenues and expenditures will grow in the short term. The political incentives to attempt to effectively bribe voters with deficit-financed dollars in advance of the next federal election will be overwhelming.

But this isn’t a sustainable trajectory for federal policymaking. The long-run challenge facing Canadian fiscal policy is rooted in the Harper-Trudeau gap. Some government will eventually need to solve it one way or the other. The arithmetic is going to eventually catch up to us.