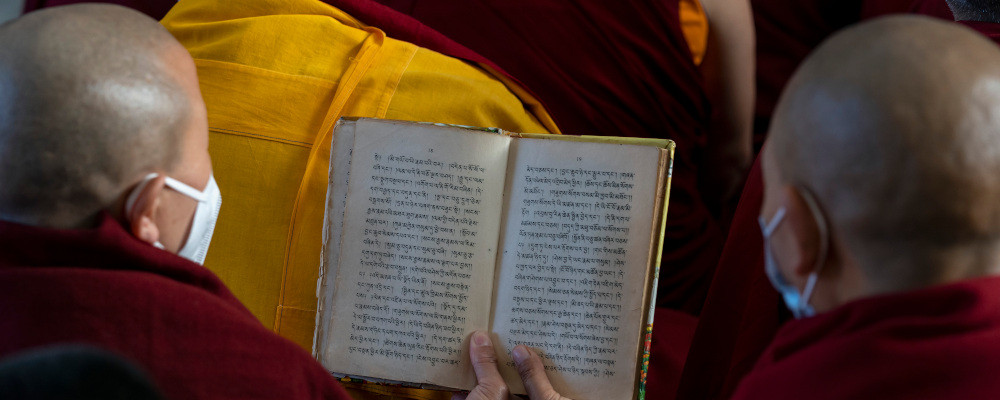

It’s no wonder The Third Eye was a bestseller. Not only did the 1953 autobiography of Tibetan Lama Tuesday Lobsang Rampa offer insight into a mysterious kingdom recently seized by the People’s Republic of China, but life as a monk was an endless adventure.

Rampa joined a lamasery as a boy and soon underwent an operation that drilled into the bone above his nose to open his third eye, granting him clairvoyant powers used to perform counterespionage in the Dalai Lama’s court. He encountered yetis and discovered the mummified body of his previous incarnation, moments that left him with sage and witty spiritual insights.

The Third Eye moved 500,000 copies in two years, giving many Western readers their first exposure to Buddhism and the plight of Tibet under Mao’s boot. It was also complete gibberish. Explorer and Tibetologist Heinrich Harrer, whose Seven Years in Tibet had been released a year prior, was so offended that he hired a private detective who revealed that Rampa was a London clerk named Cyril Henry Hoskin.

A 1958 Daily Express report exposed Hoskin. Undeterred, reprintings and future books explained that in 1949 he fell out of a tree while trying to photograph an owl, and as he recovered a Tibetan monk projecting his spirit across the globe approached him. Hoskin agreed to welcome the monk’s soul into his body, and thus a lifetime of knowledge was acquired. Convenient limitations prevented the ability to speak Tibetan from inclusion in the package.

To escape the badgering British press, Hoskin and his wife decamped for Dublin. When that distance proved insufficient, they fled to Canada. They settled in Saint John, where acquaintances recall signs of wealth: an upscale apartment, a secretary, a modern car and driver, a clock gifted to the veterinarian who cared for his precious cats. Future mayor Sam Davis was among his friends. Not bad for a high school dropout.

But Hoskin struggled to adapt to life in Canada. In 1964 he wrote Living With the Lama, although in a stroke of either marketing or insanity he claimed to have merely translated it “from the Siamese Cat language” after his Fifi Greywhiskers telepathically dictated it to him. For a book meant to shine a light on how animals are smarter than we give them credit for, there are a lot of complaints about taxes. Canada was called “so uncultured, so unfriendly” and “a cold, cruel country, with no civilised amenities such as one would have in Europe.” The cost of living was too high, the winters too cold, and the prime minister too rude to respond to his letters. Perhaps we really are trapped in an endless cycle.

Hoskin would rack up over a dozen different Canadian addresses, bouncing around Ontario and Quebec before making his way to the “more cultured, more civilised” Vancouver. He became a Canadian citizen and continued to write, each book more ridiculous than the last. Before joining the Englishman’s body, Rampa supposedly served as an air ambulance pilot in World War II, survived capture and torture, and escaped a prison camp near Hiroshima the day the bomb was dropped.

In Vancouver, Hoskin settled in a West End hotel. According to his secretary’s self-published memoir, he enjoyed the waterfront views but otherwise found Vancouver trying. He couldn’t replicate The Third Eye’s success, it had been a struggle to find a home that would accommodate his cats, and health issues necessitated the use of a wheelchair in a city unfriendly to it. Hoskin grew reclusive as his work branched out to explore aliens, premonitions of future wars, and Christ’s previously undocumented escapades.

Another relocation took Hoskin to Calgary, where he finally embraced Canadian life. 1976’s As it Was, which added even more improbable claims to his biography, was “Dedicated to The City of Calgary, where I have had peace and quiet and freedom from interference in my personal affairs.” He died there in 1981, leaving his future royalties to charities for cats.

Hoskin, depending on your own sense of charity, was either a shameless con artist or a misguided believer in his own ludicrousness. While a review had called The Third Eye “juvenile fiction,” some scholars credit it for sparking their interest in Tibet. Tibet had long fascinated the Western world; the race to sneak into forbidden Lhasa had been a thrilling if morally dubious last gasp of imperial adventure and China’s violent annexation had created a crisis that needed publicity. Hoskin was Tibet’s strangest ally in its struggle for freedom.

He was also a vanguard for New Age gibberish, work that will forever be believed no matter how often it’s debunked. A website dedicated to Hoskin claims his every word is “very true as you will discover if you remain open minded.” He added his ramblings to a bottomless slop that leads credulous believers to dangerous junk science, or at least to an annoying belief in the power of horoscopes.

But if nothing else, Hoskin was proof that interesting things can actually happen in Calgary. Ms. Greywhiskers didn’t live to see Hoskin make peace with the land of his exile, but I’ll give her the final word regardless: “Canada, we are agreed, is a most uncultured country, and all of us live for the day when we can leave it. However, this book is not a treatise on the faults of Canada, that would fill a complete library, anyway!”

Recommended for You

RCMP spending to protect MPs may have risen 112% since 2018, as Canadian politicians face greater rise in threats

Geoff Russ: A future Conservative government must fight the culture war, not stand idly by

Antony Anderson: Lucy Maud Montgomery, the ‘magazine hack’ who gave us a Canadian cultural icon

Ginny Roth: Poilievre’s picture of Canada’s future looks a lot like the Calgary Stampede