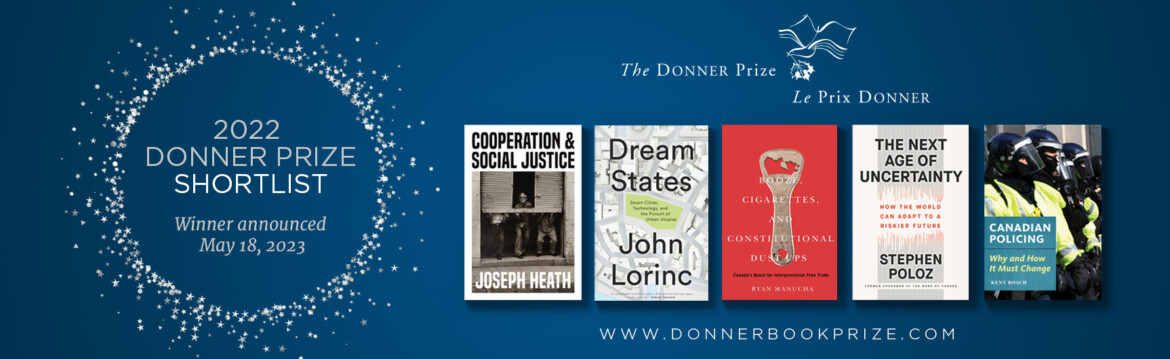

The Hub is proud to be partnering with the Donner Prize, which will be announced on May 18. We’ll be running excerpts from the shortlisted books all week and you can also listen to Hub Dialogues episodes with all the nominees. Click here to view the shortlist and get caught up on Canada’s best public policy books.

Excerpt from Booze, Cigarettes, and Constitutional Dust-Ups: Canada’s Quest for Interprovincial Free Trade by Ryan Manucha

Ryan Manucha is a scholar of interprovincial trade law. A graduate of Harvard Law, he has written extensively on the topic of Canada’s economic union for the nation’s leading think tanks and published works in outlets such as The Globe and Mail and CBC Radio. He was recently commissioned to provide policy analysis to a provincial government.

Like the story of Canada itself, the nation’s internal trade tale is still being written. Each segment of the narrative threads together the chronicle of a maturing economic union. As pre-confederation Canada transformed from Europe’s backyard garden to an independent state hungry for political autonomy and economic growth, it moved to shuck its insular colonial fiefdoms in favour of domestic integration. Gone are the days of border inspectors stationed at Coteau-du-Lac, Quebec, who monitored the passage of goods between Upper and Lower Canada flowing along the St Lawrence River.Gordon Blake, Customs Administration in Canada: An Essay in Tariff Technology (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1957).

Canadian internal commerce is now primarily governed by the rules-based order provided by the Canadian Free Trade Agreement, which supplements the nation’s section 121 “free trade” clause found in the Constitution Act, 1867. But has Canada truly left provincialism behind? There may have been no border services tower at the New Brunswick-Quebec border. Yet nearly 150 years after confederation, the Supreme Court endorsed the detainment and penalties inflicted upon Gerard Comeau by RCMP officers on account of the surplus beer he’d bought back from a liquor store located on the other side of a provincial frontier.

Focusing solely on Comeau’s legal defeat, without considering internal trade’s full account, one might falsely surmise that the Canadian project of domestic trade liberalization is in the same place as it started; that interprovincial trade barriers plague the nation just as they did the colonies of British North America. Such a conclusion, however, would ignore significant jurisprudential and political developments. Inside of one hundred years, the Supreme Court of Canada has gradually added strength to the constitution’s section 121 free trade clause. It went from an obscure paragraph meant to address those prehistoric interprovincial tariffs and customs duties to one that can now strike down modern non-tariff barriers. Section 121’s role in Canada’s legal landscape has dynamically expanded, rather than stagnate in scope. It would not be surprising if, over the next one hundred years, the nation’s highest court were to endow in section 121 even more power.

Canada’s internal trade story is a never-ending project of cross-country integration. The newest chapter of the saga is headlined by the rise of collaborative federalism, manifested in highly technical consensus-based exercises in regulatory reconciliation under the CFTA’s RCT process. Looking ahead, internal trade-barrier resolution will chiefly come from the exhaustive work of subject matter experts who are tasked with ironing out a litany of differing jurisdictional rules—on topics ranging from truck weight allowances to drug scheduling protocols—at the sustained encouragement of elected political officials.

The story of internal trade offers a means to introspect about our institutional foundations, and it also allows us to consider how Canada conceived of a national identity and its place in the world. The constitution’s internal free trade clause of 1867 was itself birthed after successive blows by foreign lawmakers seeking to protect their own interests. A loss of imperial preferences with Britain in the 1840s, followed by the termination of free trade privileges with the United States in the 1860s, forced pre-confederation Canada to look inward in order to realize grand notions of nationhood. Both shocks were at the fore of drafters’ minds as they composed a constituting document that included an internal free trade clause. National identity and internal free trade collided once again during the attempt to modify Canada’s fundamental essence following patriation in 1982. The Charlottetown Accord was an effort to redefine the Canadian state through constitutional reform, and contemplated changes to section 121 were slated to reinvigorate the economic union. These proposed modifications to the internal trade provision were an expression of a new national character.

Subsequent recourse to a domestic trade agreement in 1995 after the accord’s failure manifests the quintessentially Canadian characteristics of compromise and acceptance of diversity. Opting for an internal trade compact, rather than constitutional change, brokered a middle ground between the pursuit of national objectives on the one hand, and the sanctity of provincial autonomy on the other. It also happened to coincide with an era of popularity and salience for international trade agreements amongst Canada’s political establishment (not to mention the doctrines of neoliberalism floating through the halls of Canada’s governments and the pages of think tank memoranda).

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the fragility and vulnerability of globalized supply chains, and the renewed importance of national unity. For instance, Canadian health officials were left scrambling when the Trump administration invoked the Defense Production Act, blocking the export of crucially important N95 masks manufactured by 3M in the United States, and when the Biden administration refused to allow for the early export of US-manufactured vaccines. In many ways Canadians responded to this self-preserving isolationism and filled the voids left by foreign trading partners, just as we did when the United States abandoned the Reciprocity Treaty in 1866 and when Britain did away with favourable imperial trading preferences in 1846. As just one of many examples, Alberta sent vital medical supplies to Ontario, British Columbia, and Quebec during some of the darkest days of the COVID-19 pandemic.“Alberta to Send PPE to Ontario, Quebec and BC,” CTV News Edmonton, 11 April 2022, https://edmonton.ctvnews.ca/alberta-to-send-ppe-to-ontario-quebec-and-b-c-1.4892347

The most recent chapter of the country’s interprovincial trade story, with the CFTA’s growing primacy and collaborative model for resolving disharmonious regulations through institutionalized government-to-government negotiations, reveals that classic Canadian capacity for compromise. It balances economic unity with provincial and territorial autonomy. This acceptance of diversity has also paved the way for the many regional trade agreements that may play an increasing role in liberalizing internal trade in the years to come. There is room for a more progressive and inclusive internal trade agenda, and this may also be a part of the next chapter in the nation’s internal trade tale. Institutionalizing the participation of Indigenous peoples in Canada has been discussed in the context of international trade policy, but has not yet seeped into the conversations about interprovincial trade.

Far from a dull topic, interprovincial trade shines a spotlight revealing the history, personalities, and direction of this country. At the very least, it offers a cautionary tale about bringing back one too many lagers in the trunk of your car from your neighbouring province.

Recommended for You

Howard Anglin: Lament for a Lament

‘A place where anybody, from anywhere, can do anything’: The Hub celebrates Canada Day

Ian Holloway: The Supreme Court is ditching its iconic red robes. Yes, it matters

The Notebook by Theo Argitis: Trump halts trade talks, Carney’s trade-offs and John McCallum’s legacy