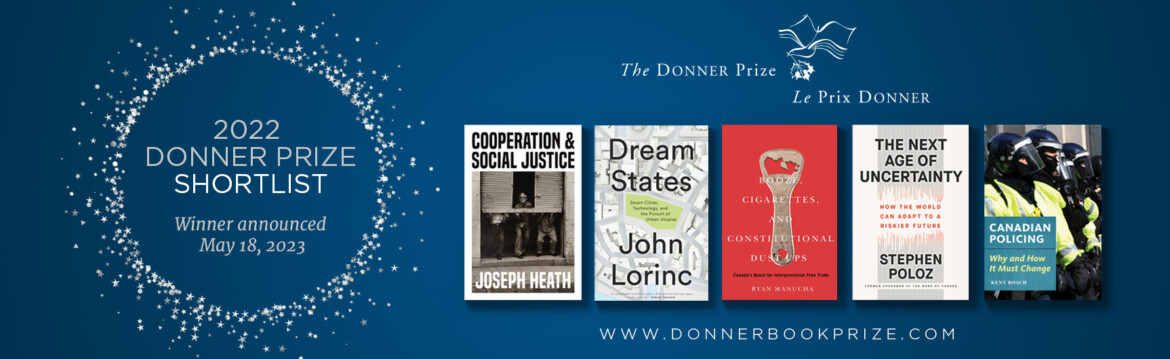

The Hub is proud to be partnering with the Donner Prize, which will be announced on May 18. We’ll be running excerpts from the shortlisted books all week and you can also listen to Hub Dialogues episodes with all the nominees. Click here to view the shortlist and get caught up on Canada’s best public policy books.

Excerpt from The Next Age of Uncertainty: How the World Can Adapt to a Riskier Future by Stephen Poloz.

Stephen Poloz is one of the world’s foremost economists with over 40 years of experience in economic and investment research, forecasting, banking, and policymaking. After a long career at Export Development Canada, ending as President and CEO, he recently finished a seven-year term as Governor of the Bank of Canada. He is currently a Special Advisor for Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP.

It goes without saying that no one wants to pay more taxes. The fractured state of politics suggests that a more nuanced, or balanced, approach will be needed to develop future fiscal plans to put more emphasis on fostering faster economic growth, thereby increasing government revenues without a significant increase in tax burdens. The irony is that this has always been a desirable approach to fiscal policy. Perhaps in the past there was always enough baseline economic growth that governments could deploy multiple taxes aimed at pleasing special interests, and the attendant loss of economic growth was not all that noticeable. But with economic growth now slowing as baby boomers exit the workforce, every decimal point of economic growth seems more meaningful, even in the face of polarized politics.

The preferred form of taxation from an efficiency and growth point of view is to tax consumer spending, not income, using sales taxes. Taxing spending, instead of income, causes people to work more and save more, which provides more capacity for investment by firms in future economic growth. Taxing spending has the added benefit of applying equally to retired individuals, which makes it a more sustainable form of taxation in an aging society. Despite these attractive features, many argue that consumption taxation is “regressive”—that it worsens the after-tax income distribution because low-income individuals spend their entire income, whereas high-income individuals spend only a part of theirs. Income taxes normally do not have this problem, as they are “progressive”—the percentage paid rises as income rises. But it is easy to introduce consumption tax rebates at the low end of the income scale to adjust for this issue, thereby negating the objection. Canada has such a consumption tax rebate system. Even so, consumption taxes are often seen as politically difficult to implement, because consumers see the tax every time they buy something and are reminded too often who imposed the tax on them.

Consider a thought experiment. Suppose that a government were to simplify the currently complex tax structure by calculating the sales tax rate that would need to be deployed to replace all other taxes and keep government revenues unchanged. The simplest possible example would be to eliminate income taxes and various corporate taxes altogether, except perhaps on the highest incomes, and raise the sales tax to keep government revenues the same. If these two changes were made on the same day, leaving everyone as well off as before, would that be politically impossible? My guess is that most people would shrug and carry on, as there would be no change in the money in their pocket. But from a macroeconomic point of view, the result would be a far more efficient economy with a faster trend growth rate and higher fiscal revenues as a result.

Introducing tax reforms that move the burden from working to spending might even be politically attractive in the post-pandemic context. There is a widespread expectation that tax burdens on companies and individuals alike need to increase significantly in order to repair the fiscal damage done by COVID-19. Consider a second thought experiment. Suppose everyone is dreading higher taxes to pay for the debt incurred during the pandemic, and instead governments announce that they are reforming current tax policies in such a way that no taxes rise, economic growth increases, and government revenues go up automatically. The political mileage to gain from the collective relief is incalculable. Making such an initiative politically palatable, however, would require considering it as a balanced, all-or-nothing package—since all the pieces interact with one another, debating and compromising on the individual changes would erode the benefits and take it to certain political defeat.

A tax reform that leaves tax rates unchanged while boosting economic growth would give a highly indebted government considerable fiscal flexibility. Higher economic growth would mean that the ratio of government debt to national income would be falling, reassuring markets and the general population that government capacity was being built up to prepare for the next crisis. The decline in the debt-income ratio could be accelerated, if preferred, by allocating some or all of the new growth in government revenue to a faster retirement of debt.

The fact remains that the most important ingredient in economic growth is people, so the plethora of government policies that impact labour force participation need to be considered together. To see the power of investing in daycare infrastructure, one need only consider the system created in Quebec over twenty years ago, which fostered a significant increase in female labour force participation. If similar policies were deployed Canada-wide, and the national female labour force participation rate could be boosted to near that for men, total income in the economy could be raised significantly—by 2 percent easily but possibly far more. This potential gain and the associated new tax revenues need to be considered when deciding whether additional government investment in childcare is economically sensible. Calibrated properly, a program like this can essentially pay for itself, given the additional revenues generated by the higher potential output. Unfortunately, government spending on social infrastructure is usually regarded as a fiscal outlay, not an investment.

Often such structural changes are described as “politically impossible”; examples from Canada include reforming supply management systems for dairy products, eggs, or chicken and liberalizing international or interprovincial trade. This political impossibility arises essentially because those who perceive that they would lose as a result of the change have their voices magnified by news media and social media and create serious political fallout for the government. But if governments are confident that the policies would improve economic growth, the change would create a fiscal dividend, along with being a positive for the majority of Canadians. It is a simple exercise to estimate those fiscal benefits and allocate some (or even all) of them in advance to those most likely to be negatively affected, thereby compensating those who will lose and winning the macro argument at the political level.

Recommended for You

Ginny Roth: J.D. Vance, Pierre Poilievre, and how they slice their economic pie

David Polansky: As President Biden leaves the race, will the Democratic Party hodgepodge hold?

RCMP spending to protect MPs may have risen 112% since 2018, as Canadian politicians face greater rise in threats

Trevor Tombe: Canadians are paying billions in hidden taxes on new homes