I admire and respect New York Times columnist David Brooks. His political analysis—including his underrated thinking on “national greatness” conservatism in the late 1990s—and his more personal writing—including his 2015 book The Road to Character—have had a meaningful effect on me. He’s someone that I’ve regularly turned to make sense of culture, ideas, and politics.

So I wasn’t surprised that his recent column on the role that the “winners” of the modern economy have inadvertently played in creating the economic and social conditions for Trumpian populism has received such widespread reaction.

It’s a thoughtful piece of analysis about big changes in our economy and society, how certain people and groups have navigated these changes better than others, and how they’ve come to create an interconnected system of education, employment, institutional leadership, familial and social relations, and cultural norms and signals that perpetuates their advantages. As Brooks writes:

The ideal that we’re all in this together was replaced with the reality that the educated class lives in a world up here and everybody else is forced into a world down there. Members of our class are always publicly speaking out for the marginalized, but somehow we always end up building systems that serve ourselves.

His column is an important and necessary reckoning with the factors that have caused large shares of Western societies to become anxious about the present and pessimistic about the future. It’s far more constructive than many in his circles who are satisfied to dismiss the concerns of their fellow citizens as mere expressions of backwardness, ignorance, or racism. Brooks deserves tremendous credit for his empathy and self-introspection.

Much of his analysis is persuasive. It’s clear that the shift from a goods-producing economy to a knowledge economy has preferenced those with certain credentials and skills as well as particular regions and communities. The trickle-down effects, including on marriage and families, broader social relationships, and of course politics have been profound.

Yet as important and insightful as the essay is, it suffers from one major flaw. It assumes that “meritocracy” and “credentialism” are essentially synonyms. They are not.

Although it’s of course true that many, perhaps most, of the winners in the modern economy are highly educated, there are still some who have succeeded without educational credentials and an even bigger share that are failing in spite of them.

The latter group—let’s call them “overeducated underachievers”—strikes me as crucial for understanding growing pessimism about the future, the rise of populism, and the anger and frustration that we’re increasingly seeing manifest itself in our politics.

The rise of the working-class university graduate

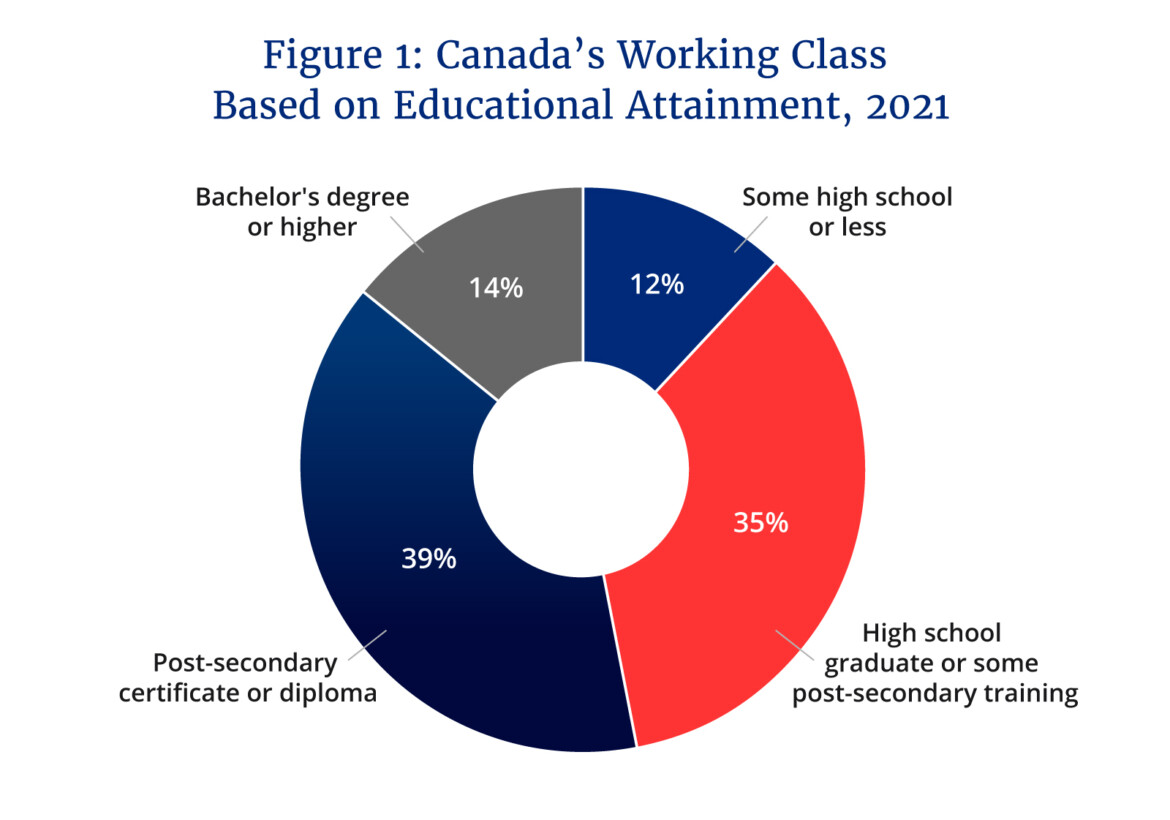

Last year, I co-authored a paper for the Cardus Institute on Canada’s modern working class. We defined working class as those in occupations that typically don’t require post-secondary credentials. One of our most surprising findings is that 53 percent of those in working-class jobs actually have post-secondary certificates, diplomas, or degrees (see Figure 1). This group excludes full-time students so their “underemployment” cannot be explained as merely a transitory step in their careers.

There are no doubt various factors at play, including individual preferences, foreign credential issues, a geographic skills mismatch, or even employer discrimination. But a major contributing factor is the interplay between the rise of credentialism—the idea that one’s ability or intelligence is measured by their academic credentials—and what is sometimes referred to as “credential inflation”—the economy-wide trend of rising expectations with respect to educational credentials required for a job.

British thinker David Goodhart argues that these economic and social currents have caused us to “overshoot” when it comes to education and training. We now appear to have a large-scale overeducation problem in advanced economies including Canada.

Consider for instance a growing body of research on the rise of these “overeducated underachievers” and their labour market experiences and outcomes. The numbers are quite striking. A major 2014 study for instance found that in the United States about 37 percent of four-year college graduates tend to have more education than their jobs require. Goodhart’s more recent work on the United Kingdom shows that more than a third of university graduates are in non-graduate employment more than five years after graduating. Previous research by the Parliamentary Budget Office finds similar outcomes for Canada.

Although these overeducated workers tend to earn more than less educated workers in the same occupation, they earn a lot less than similarly educated workers in occupations that match their credentials. They also tend to remain overeducated over the long run. One consequence is the wage penalty for their overeducation similarly tends to persist. Another is that these workers report having low levels of job satisfaction as well as self-reported bouts with anxiety, depression, and other mental health challenges.

Those affected have fallen between the cracks of Brooks’ conception of the meritocracy and the real-life experience with modern credentialism. They’re the ones who “did everything they were expected to”—including obtaining a university or college credential—and yet haven’t realized the payoff. In Canada, for instance, they’re earning on average 41 percent less than those in non-working-class jobs and, depending on where they live, struggling to afford rent and other basic costs. The promise of the so-called “democratization” of educational access has failed to fully materialize for them and their families.

There’s a strong case in fact that while there have been significant benefits to expanded access to post-secondary education, they’ve come with these underestimated costs that we’re only now starting to understand. Cultural norms and public policies in favour of what Goodhart calls “peak head” has devalued non-cognitive skills, eroded academic standards, and contributed to credential inflation in the job market. Put bluntly: there are people with advanced degrees who shouldn’t have them and the market has had to adjust to account for them.

These people themselves cannot be blamed for these developments. They’ve responded to the same elite signals and social norms about the utility of post-secondary credentials that are implicit in Brooks’s essay. They got good enough high-school grades to get accepted into university or college programs which they ultimately completed. They may even have subsequently done an advanced or professional degree. Yet they’ve still been overlooked or rejected by the meritocracy.

What’s behind the rise of modern credentialism?

It’s interesting to think about what has caused the educated leadership class—including business, cultural, and political leaders—to cultivate such powerful social expectations. What is behind the rise of modern credentialism?

A major factor undoubtedly is a progressive view about education, intellectual knowledge, and human progress. There’s an inherent assumption that expanding education is the key to unlocking a version of utopia in which an expanding “cognitive class” can overcome the class struggles of the old goods-producing economy. It also captures the inclusive ideal of meritocratic thinking and the role of education as the “great leveler” in society. The “university for all” crowd is a good example of this ideological tendency.

Another may be the cause of self-selection bias. If everyone around key decision-making tables in society has post-secondary credentials, it’s not a huge surprise that they’d cultivate social norms related to education that would tilt in favour of their own backgrounds and experiences. Duke University professor Nicholas Carnes’ work on the so-called “white-collar government” (which refers to the narrowing of educational backgrounds and professional experiences of members of the U.S. Congress) has documented how the growing homogeneity of the political class influences broader policymaking including with respect to education.

Goodhart argues that it’s not merely bias. It also reflects in his words “an indiscriminate spirit of not wanting to kick away the ladder on the part of people who have had valuable university experience themselves.” Yet the problem with this type of thinking is that it imposes one’s own attributes and preferences on the rest of society. It may be well-intended but it’s also narcissistic. It counterintuitively undermines pluralism in the name of inclusion. Real inclusion would strive to enable people to pursue their own interests and maximize their own strengths rather than presuming the right path for them.

My own hypothesis is that the massive cultural and political emphasis on post-secondary education in recent decades is itself a sign that the leadership class doesn’t know what to do. A combination of factors—including globalization, public policy, and technological change—has transformed the modern economy from an “economy of things” to an “economy of thoughts.” The resulting “skills-biased technological change” is reshaping market demand, employment opportunities, and earnings based on certain credentials and skills.

Policymakers have struggled to keep up with or even make full sense of these developments. In the absence of a clear understanding of the long-run implications for the economy and society, an expansion of post-secondary education has become the default response. A growing population of overeducated underachievers is its byproduct.

A bourgeois revolution: The real risk of political disruption

The gap between the promise of credentialism and its disappointing realities for rising numbers is something that we must confront before it engulfs our politics. For all of the attention paid to the threat posed by working-class populists, the real risk of political disruption may actually come from the rise of white-collar populists.

The latter has good reasons to be agitated. They were led to believe that educational credentials were a path to social mobility and membership in the meritocratic class. Yet they instead find themselves in lower-paying and more precarious work than their typically uneducated parents. The real revolutionaries in other words may not be the proletariat but the disaffected and unfulfilled bourgeois.

University of Connecticut scientist Peter Turchin has been warning about this risk for more than a decade. In a 2010 article for the science journal Nature, he predicted the rise of today’s political instability due in part to what he called “elite overproduction.”

The basic idea is that our societies are training and producing more highly-educated individuals than there are elite positions in business, government, or other key institutions. This supply-demand gap threatens the rise of counter-elite movements that may eventually aim to overthrow the political order. He points to historic examples like the French Revolution, the Russian Revolution, and even the American Civil War as evidence of his theory.

Turchin has returned to this theme in a new book entitled, End Times: Elites, Counter-Elites, and the Path of Political Disintegration. In it, he uses a metaphor of musical chairs to convey his argument:

I use a metaphor of playing a game of musical chairs, but instead of removing chairs one at a time, you keep adding more and more players. And so as they’re twice as many, three times as many, players as there are chairs, you can imagine how much chaos would ensue. This is a good metaphor for our societies because elite aspirants typically are energetic, ambitious, well-educated, good at organizing, and therefore when they’re frustrated in getting the positions that they expect, many of them turn to trying to infect, overthrow, the unjust social order as they perceive it.

For these reasons, he warns that “disgruntled elite-wannabes are far more threatening to societal stability than disgruntled workers.” Their growing ranks therefore ought to be the subject of far greater political and policy attention.

Which brings us back to Brooks’s essay. Although he’s right to look inward at the role that educated elites have played in contributing to the rise of contemporary populism, his conclusions aren’t quite correct. The chief problem isn’t less-educated classes or meritocracy itself. It’s the flawed culture of credentialism and its diminishing returns on educational credentials for legions of overeducated underachievers that may ultimately prove to be his class’s gravest mistake.

If you don’t like working-class populists, you’re going to hate the white-collar populists. Unless, of course, you are one.

Recommended for You

Ian Holloway: The Supreme Court is ditching its iconic red robes. Yes, it matters

DeepDive: Canada’s universities are failing to provide proper civic education. Here’s how Alberta can correct course

Sean Speer: Don Cherry deserves the Order of Canada

The Notebook by Theo Argitis: Trump halts trade talks, Carney’s trade-offs and John McCallum’s legacy