Against the backdrop of COP28, we appear to be in the midst of yet another constitutional confrontation between Ottawa and the provinces over who has the authority to regulate greenhouse gas emissions and whose net zero climate plan will ultimately guide emissions reduction targets.

The latest flashpoint occurred yesterday in response to Trudeau’s announcement of Canada’s planned oil and gas emissions cap. This announcement came on the heels of two others shortly before COP28—those being the federal government’s commitment to creating a net-zero electricity grid by 2025 under the Clean Electricity Regulations (CERs), and the 75 percent reduction target for oil and gas methane emissions by 2030 under the draft Oil and Gas Methane Regulations.

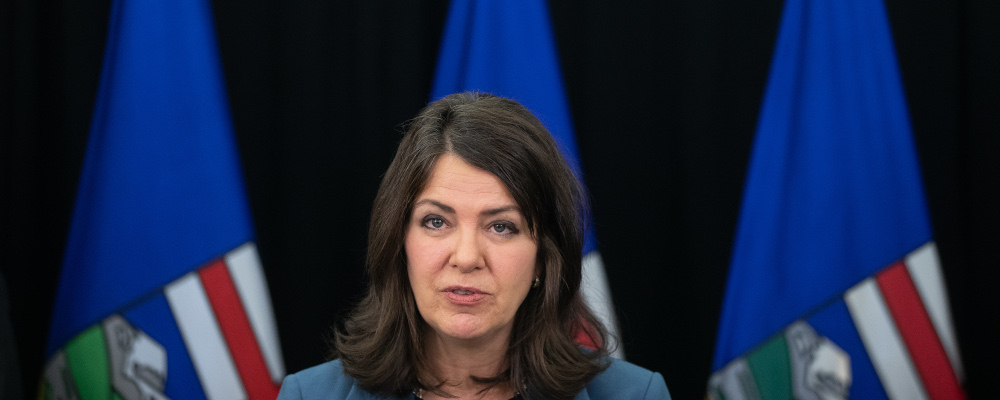

Alberta and Saskatchewan—no doubt emboldened by recent court rulings against the federal Impact Assessment Act (IAA) and a single-use plastics order—consider all three to be unconstitutional intrusions into provincial jurisdiction of natural resources. Alberta has taken the occasion to invoke the Alberta Sovereignty Within a United Canada Act, and on November 28th tabled a resolution in the Legislative Assembly aimed at contesting the CERs. Federal Environment Minister Guilbeault has characterized Premier Smith’s actions as merely “symbolic,” and appears steadfast in his position that the latest barrage of ambitious federal climate policies is firmly within the purview of federal jurisdiction.

While much needs to be unpacked regarding the constitutionality of the emissions cap and methane regulations, the CERs at a minimum appear ripe for a constitutional challenge and perhaps offer insight into how courts might approach Ottawa’s ongoing attempts at regulating GHG emissions. Putting aside the ongoing debate about the Sovereignty Act, it is worth considering the substance of Alberta’s concerns. Are the CERs unconstitutional? This is an important question to ask. Particularly in light of the constitutional gridlock Canada finds itself in, where competing federal and provincial climate plans, compounded by divergent regional priorities, have spurred endless litigation, and persistent commercial uncertainty.

In their draft form, the CERs have all the trappings of another jurisdictional dust-up. Constitutional controversy appears baked into the DNA of the regulations, as well as Ottawa’s forthcoming oil and gas emissions cap. Both are unilateral attempts to regulate and cap GHG emissions at their source: generation facilities and oil and gas production. The “Performance Standard” at the centre of the CERs, for example, prohibits electricity generation units with a capacity of 25 megawatts (MW) from emitting more than 30 tonnes of CO2 per gigawatt hour (GWh) of electricity generated. In essence, the regulations form a comprehensive federal framework aimed at limiting CO2 emissions from electricity generated by fossil fuels, with the eventual goal of eliminating such sources from public electricity grids in Canada.

It is difficult to imagine how such a far-reaching scheme—however laudable its underlying policy objectives may be—would not impact provincial jurisdiction over non-renewable natural resources and electricity generation, both of which are expressly and exclusively protected under section 92A of the Constitution Act.

In the event of a constitutional challenge to the CERs or emissions cap, it is expected that Canada would invoke either the federal “Peace, Order, and Good Government” power (POGG) or its criminal law power. If recent decisions are any indicator—including those holding that the federal Impact Assessment Act (IAA) and a single-use plastics order are unconstitutional—it is not plainly obvious that Canada would succeed.

In the IAA Reference, the Supreme Court rejected Canada’s argument that Parliament’s POGG power could support its purported ability to review and regulate resource projects on the basis of GHG emissions. Of particular relevance to the CERs, the Court was clear that while specific national mechanisms like pricing could be justified under POGG, as was the case in the GGPPA Reference, broader regulation concerning “GHG emissions generally” and “sector-specific initiatives concerning electricity, buildings, transportation, industry, forestry, agriculture, and waste” are likely to fall outside of its ambit. The CERs—as well as both oil and gas and methane emissions caps, for that matter—seem to resemble the type of broad regulatory approach to GHG emissions that the Supreme Court has cautioned against. At first blush, the POGG power does not seem to offer a solid constitutional footing for the CERs.

This leaves Canada with the criminal law power, which is seen by some as the more viable head of power from which to mount a constitutional defence. However, there are compelling reasons why the application of the criminal law power, despite having some precedent, is not a straightforward path for the CERs.

As a starting point, the Supreme Court has not allowed the criminal law power in the environmental context since 1997, when a divided Court in R v Hydro-Quebec upheld a “specific” and “discrete” ministerial order prohibiting polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). Since Hydro-Quebec the use of the criminal law power has been highly contested and subject to significant doctrinal uncertainty, particularly when applied to complex laws that are regulatory rather than criminal in nature, or where the criminal law is not properly “calibrated to the harm” (i.e., prohibiting an activity that is not in itself harmful, in order to prevent the harmful or dangerous forms of that activity). Courts have also repeatedly warned that laws authorized under the criminal law power must not be “so broad or all-encompassing as to be found to be, in pith and substance, really aimed at regulating an area falling within the provincial domain,” given the “potential to upset the constitutional balance of federal-provincial powers.”

And therein lies the constitutional risk inherent to the CERs. They directly and comprehensively invade the territory of electricity generation, through a sweeping “prohibition” on CO2 emissions. Canada itself acknowledges that the regulations will have a clear impact on provincial electricity grids; particularly in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and New Brunswick, where significant investment and build-out of electricity system technologies will be required in order to comply with the federal emissions standard. While purporting to maintain “technology neutrality” and “minimiz[e] economic impacts,” the regulations effectively necessitate a significant redirection of investment away from natural gas-powered generation to emerging and costly clean energy technology like carbon capture and storage, clean fuels, small modular reactors, and battery storage.

The practical effect of the regulations is that provinces such as Alberta, Saskatchewan, and New Brunswick will be left with little choice but to replace or offset their non-renewable electricity generation with investment in technologies preferred by Canada. This will invariably alter the composition, operation, and costs of provincial electricity grids, particularly in Western Canada. And in doing so, the regulations push to the side provincial policy choices that section 92(A) is designed to preserve. There is a reasonable argument that this is the exact type of “all-encompassing” use of the criminal law power that the SCC has cautioned against.

At this stage, given that the regulations remain in draft form, a constitutional challenge is likely premature. The Premier’s invocation of the Sovereignty Act, therefore, may be seen as a final attempt at dialogue and compromise with the federal government before it officially promulgates the CERs. Failing a cooperative resolution, however, the current drafts of the CERs are at significant risk of crossing the dividing line into provincial jurisdiction and ultimately missing the constitutional mark. At a minimum, they are a far cry from the legislation upheld 26 years ago in Hydro-Quebec. This is fertile ground for a constitutional challenge.

As we stand by for the final publication of the regulations, it is hoped that Ottawa and Alberta can avoid another constitutional battle by heeding the recent advice from the Supreme Court to seek “cooperative solutions” to environmental protection “that meet the needs of the country as a whole as well as its constituent parts”.

Recommended for You

Is Carney’s ‘grand bargain’ anything more than an empty gesture?

Carney finally goes big

The question is not whether liberty should be ordered, but how

David Eby has one big pipeline-sized problem