As the federal Parliament returns from its summer recess, there are a number of big economic and fiscal questions that will loom over the upcoming parliamentary session. They speak to some of the growing anxieties that Canadians are feeling, the key political fault lines between the major parties, and issues that will ultimately animate the next federal election.

Here are six charts that bring expression to these economic and fiscal questions that may shape the parliamentary sitting.

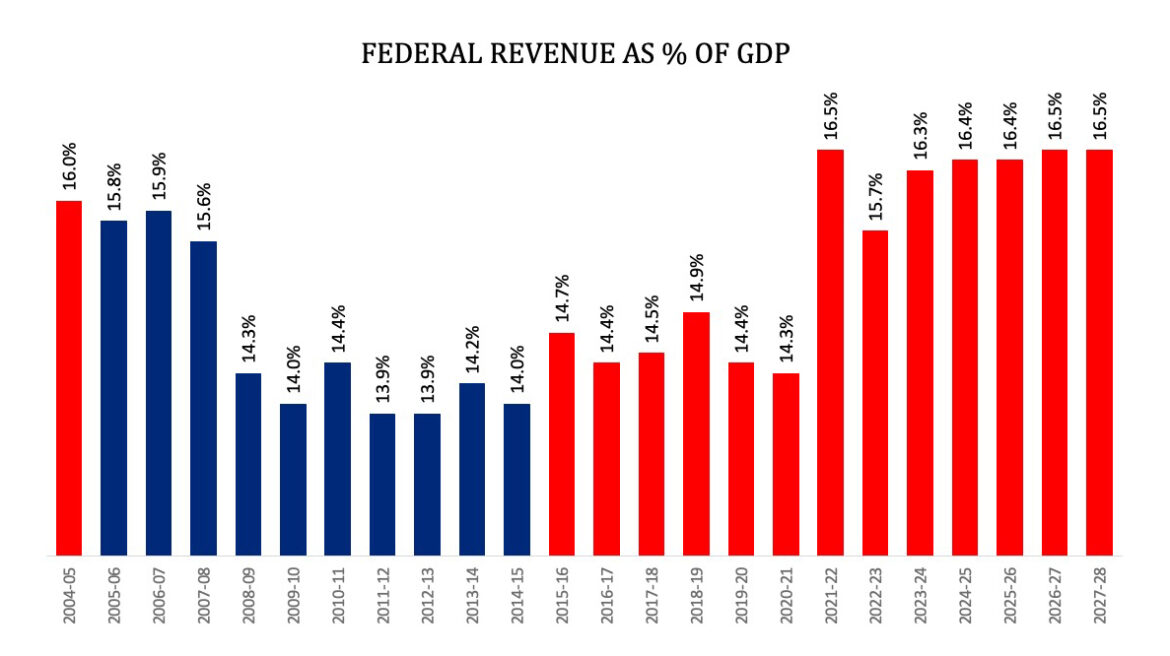

1. Ottawa doesn’t have a revenue problem…

One of the most underreported stories of the Trudeau government’s fiscal policy has been the gradual increase of federal revenues as a share of GDP from the record lows of the Harper government to levels that now match where they stood more than 20 years ago.

There are different explanations but the two biggest are (1) higher energy prices have pushed up corporate profitability and in turn corporate income tax revenues, and (2) the federal carbon tax, which is responsible for about 0.6 percentage points of the increase in the chart.

The key point here though is that the Trudeau government cannot balance the budget on a revenue base that is two-and-a-half-percentage points higher than the previous Conservative government.

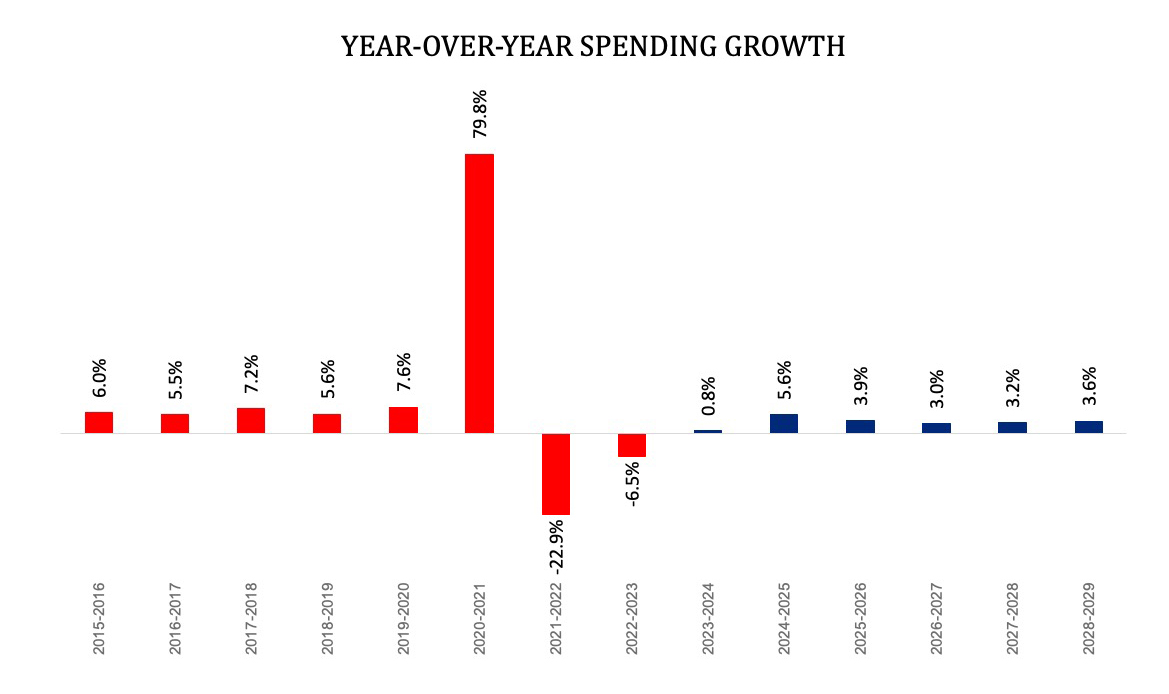

2…it has a spending problem

The problem of course is the government’s sustained spending growth. Program spending grew on average by 6.4 percent in the Trudeau government’s first five years in office prior to the pandemic. One has to go back to the 1970s to find a five-year span with similar rates of spending growth. (In comparison, the last five years under the Harper government saw program spending grow by an average of just 0.5 percent per year.)

As we look ahead, the government’s fiscal projections are doubtful. After growing spending by more than 6 percent it in its first five years (excluding the pandemic), it now proposes that program spending will grow by roughly half that amount over the next five years. There are few reasons to believe that it will actually stick to these projections—especially in light of pharmacare and other outstanding progressive priorities.

It’s also a reminder that even an incoming Conservative government will face a constrained fiscal context. All things being equal, even limiting program spending growth to 3 percent per year (which will be challenging in light of pre-existing spending commitments and outstanding spending pressures) won’t produce a balanced budget in this decade.

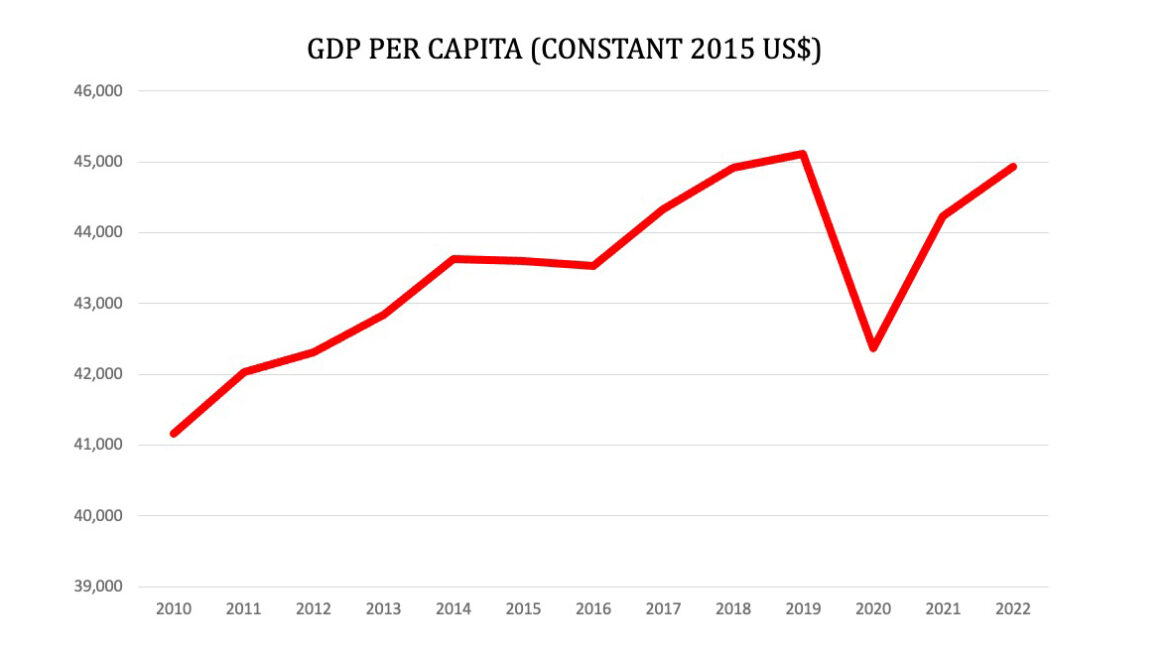

3. Canadians are getting poorer

There’s been a lot of discussion in recent weeks about Canada’s poor performance with respect to GDP per capita. Although we may not be in a technical recession, we’ve experienced long and deep recessionary conditions for Canadian living standards. This presumably explains a lot of the economic pessimism that we’re seeing in public polling.

Canada’s GDP per capita actually declined last year and remains roughly $1,000 per person and $2,500 per household below pre-pandemic levels. This puts us among a small number of OECD countries that haven’t yet recovered from pandemic losses. It’s now not expected to recover until 2027.

There is some debate about the relative role of different factors, including the inherent trade-offs between capital and labour, for explaining this alarming trend. But few voices contest its consequences. It’s not hyperbole to say that Canada has experienced something of a lost decade of stagnant or declining living standards that will have permanent consequences for Canadians’ wealth and well-being.

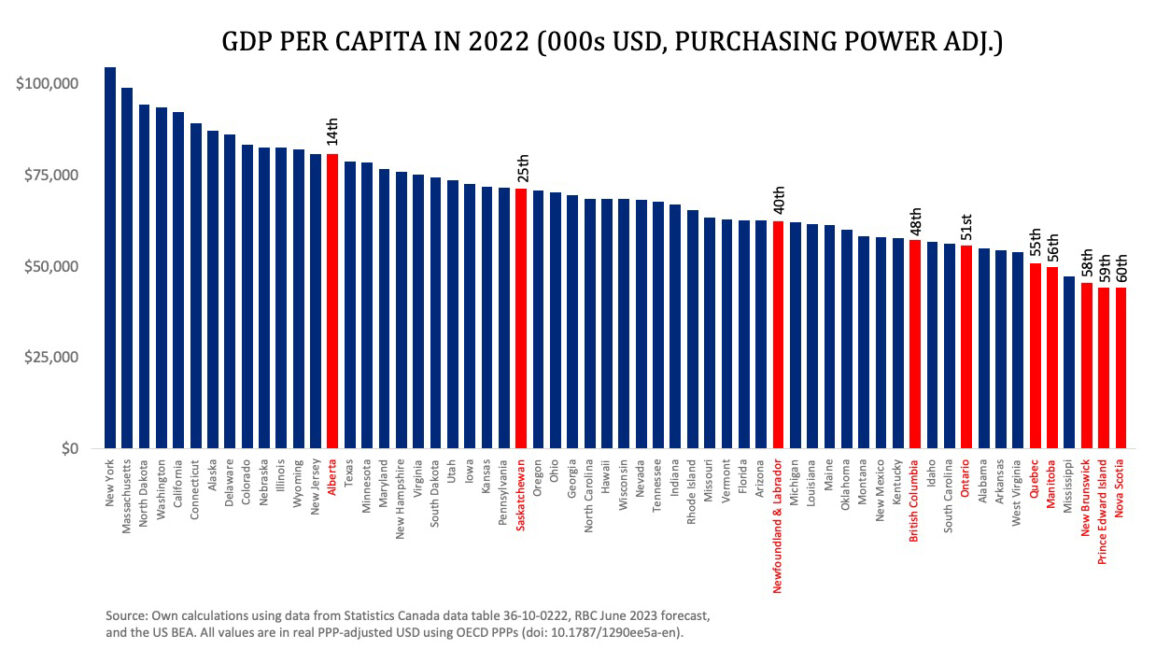

4. We’re falling further behind the U.S.

One way to understand those consequences is to compare Canada to the United States, as University of Calgary economist Trevor Tombe did in a Hub article in June 2023. His key finding has generated a lot of attention: most Canadian provinces lag far behind almost all U.S. states.

Ontario, for instance, has a per-person level of economic output that’s similar to Alabama. The Maritimes are below Mississippi and Quebec and Manitoba lag West Virginia. Only Alberta exceeds the U.S. average of $76,000, but even our strongest province ranks only 14th overall.

The growing lag between our two countries could have various medium-term consequences including, as University of Waterloo economist Mikael Skuterud recently warned in a conversation with The Hub, the risk of so-called “brain drain” by prospective immigrants and Canadian citizens.

5. We have a less dynamic economy

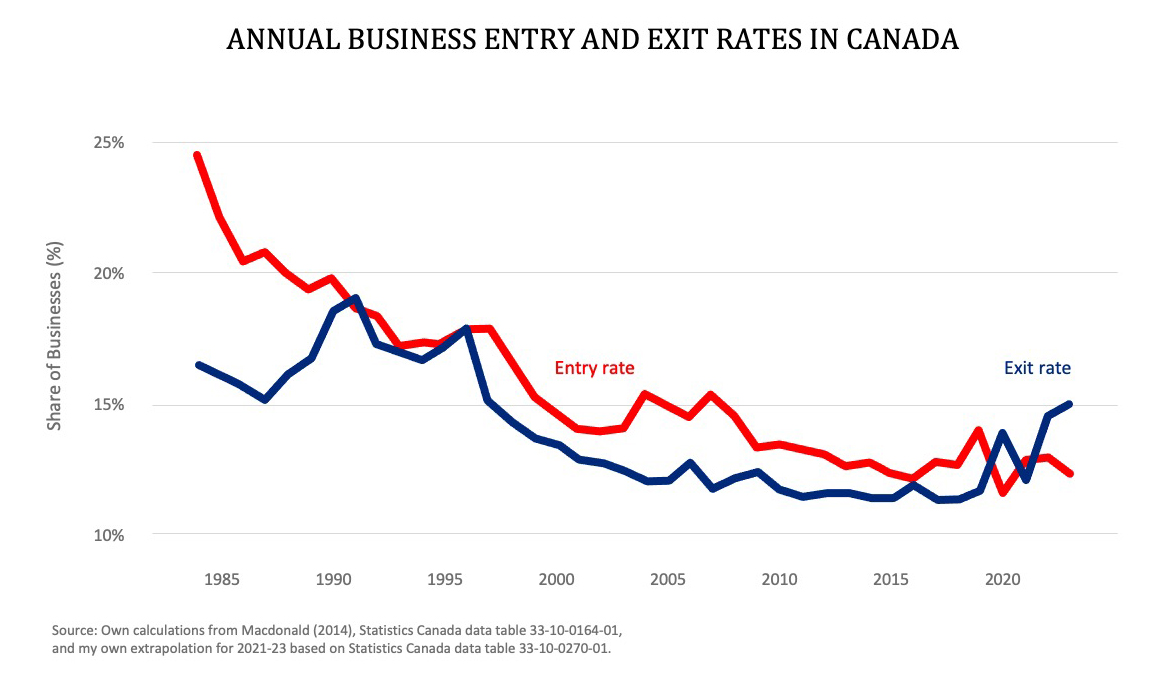

Tombe recently highlighted another example of Canada’s economic stagnation in the form of the growing gap between business start-ups and bankruptcies.

The latter are now at levels not seen since the 1990s. That might be okay if not for the fact that the former is also at all-time lows. Firm entries into the market are half the rate of the mid-1980s and far below the rate of firm exits.

These trends require some reflection on how we ought to think about what’s happening in Canada’s economy. As Lakehead University Livio Di Matteo recently set out in The Hub, there are two types of economic growth: extensive growth and intensive growth. The former reflects an increase in the total size of the economy. The latter is concerned with an increase in GDP per person which ultimately depends on whether inflation-adjusted GDP grows faster than the population.

The Trudeau government has mostly pursued a policy of extensive growth. It has increased the population, run a loose fiscal policy, and increased cash transfers. This mix of policies will by definition boost the country’s gross domestic product—it has probably in the past year even caused us to avoid a technical recession—but it doesn’t drive intensive growth. In fact, to the extent that the rise in low-skilled labour has distorted business investment decisions, it may be detrimental to intensive growth. I’ve previously described it as an economic agenda of “empty calories.”

Canada’s economy instead needs a policy agenda focused on intensive growth—namely, boosting business investment. That ostensibly involves some combination of regulatory reform, competition reform, and maybe some mix of tax incentives.

The key point here is that while there’s been a lot of exogenous forces in the economy, it would be wrong to think that government policy has no role in where we currently find ourselves. In fact, in some ways, the Trudeau government’s policy of extensive growth has delivered precisely what one would have predicted: a modest boost in overall economic activity but a decline in the economy’s competitiveness and dynamism.

6. There’s a growing rural-urban divide

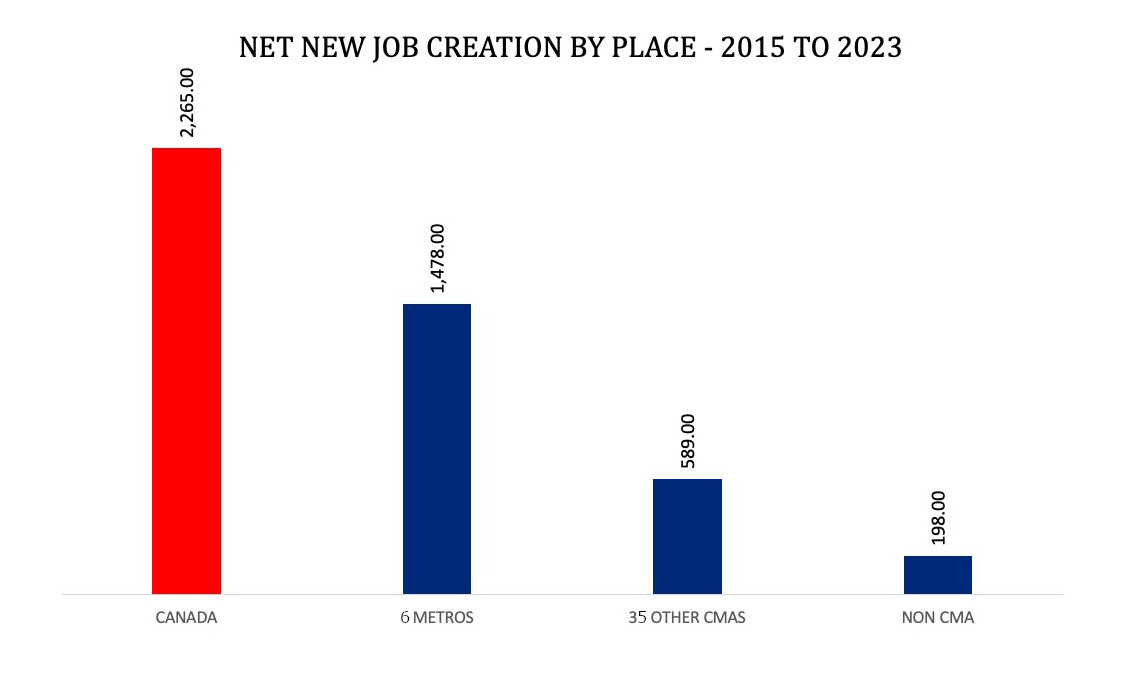

One final issue that may be something of a sleeper topic is the extent to which Canada’s story of investment and job creation over the past decade or so is essentially about the country’s six major metros: Montreal, Toronto, Vancouver, Ottawa-Gatineau, Calgary, and Edmonton.

They represent roughly 47 percent of Canada’s population, slightly more than half of its economic activity, and, between 2015 and 2023, they were responsible for more than two-thirds of all net new job creation in the country.

If one adds the other 35 census metropolitan areas, the total percentage of the population rises to about 70 percent, the share of the economy goes to roughly 75 percent, and net new job creation since 2015 reaches more than 90 percent.

The rest of the country—including smaller and rural communities—was home to less than 9 percent of net new jobs over this period.

This degree of place-based economic concentration may represent a political economy problem for a few different reasons: (1) Canada’s model of hyper-urban agglomeration has contributed to its out-of-control housing costs as well as the ongoing concentration of immigration settlement in a small number of major cities, (2) rural and economically-distressed communities are facing various socio-economic challenges (including rising crime rates) rooted in a lack of opportunity, and (3) there’s a risk of growing socio-political issues between dynamic and stagnant parts of the country.

Addressing these issues will require a mix of policy interventions. One idea that the government ought to explore is the adoption of the U.S. model of Opportunity Zones, which, according to recent research, is showing some promising signs.

Recommended for You

The Weekly Wrap: Stop painting Alberta as the villain of Canada

Where the CBC went wrong

The Week in Polling: Majority of Canadians want the Alberta-B.C. pipeline; Optimism about the Carney government drops; 87 percent of Canadians concerned about the state of housing

‘An approach that lacks principles’: The Roundtable on Canada’s confusing China reset and the lack of scrutiny on Carney