This past weekend, 200 lawyers, law students, and scholars from across Canada gathered at the University of Toronto’s Hart House for the seventh annual Runnymede Society conference. Entitled “Law & Freedom 2024”, the event addressed everything from how we should view the Emergencies Act following a landmark Federal Court ruling that found its one and only use unconstitutional, to free expression, to federalism.

Founded in 2016, the Runnymede Society is a non-partisan organization of lawyers, law students, and legal scholars that describes itself as being “committed to the principles of constitutionalism, the rule of law, and fundamental freedoms.” The group can be broadly characterized as right-of-centre, with many of its members identifying as libertarian, classically liberal, and conservative. A product of the Canadian Constitutional Foundation, the society produces original debates, journal publications, and networking opportunities meant to challenge conventional thinking in Canada’s legal community. It now boasts chapters in many of Canada’s law schools.

“We cannot take for granted intellectual diversity in the legal profession,” insisted outgoing Runnymede Society national director Kristopher Kinsinger, kicking off this year’s series of discussions.

The 2024 keynote lecture was delivered by Supreme Court Justice Malcolm Rowe. The Hub’s managing editor Harrison Lowman was there to cover the address. Below is an exclusive excerpt from his speech, entitled “Constitutionalism in a Free & Democratic Society.”

What is the impact on democratic institutions of an expanding role by courts in determining public policy?…[My] focus isn’t on what courts do or how they do it. Rather, it is on the consequences of courts expanding public policy role on the operation of democratic institutions.

…Forty years ago, Peter Russell…predicted that political issues would be transformed into legal ones. He expressed concern with what he called the “negative side” of “transferring policymaking from the legislative to the judicial arena.” This transfer, he wrote, “represents a further flight from politics, a deepening disillusionment with the procedures of representative government and [of] government by discussion as a means of resolving fundamental questions of political justice.”

Thirty years ago in “Judicial Power and the Charter,” Christopher Manfredi was even more direct; he warned of an “imperial” judiciary whose authority would undercut democratic institutions. He wrote, “The problem with judicial social engineering…is that the attempt to correct the errors of democratic institutions through litigation…risks undermining the capacity for self-government on which liberal democracy ultimately depends…Too great a reliance on…litigation can both exacerbate social conflict and enervate public discussion of important political questions.”

Twenty years ago in “The Charter Revolution,” Morton & Knopff wrote that, “Encouraged by the judiciary’s more active policy-making role, interest groups…have increasingly turned to the courts to advance their policy objectives…Not only are judges now influencing public policy to a previously unheard-of degree, but lawyers and legal arguments are increasingly shaping political discourse and policy formation.” They concluded that “Liberal democracy works when majorities rather than minorities rule, and when it is obvious to all that ruling majorities are themselves coalitions of minorities in a pluralistic society. Partisan opponents…must nevertheless be seen as fellow citizens who might be future allies. Representative institutions facilitate this fundamental democratic disposition; judicial power undermines it.”

Recently, Dave Snow & Ted Morton wrote in “Law, Politics and the Judicial Process” (4th ed) that “To adapt [Peter] Russell’s formulation… if populism reflects a flight from representative government and government by discussion, [deciding policy under] the Charter represents a further flight.” Mark Harding’s book, Judicializing Everything addresses these issues at length.

These political scientists share the view that for democratic institutions to function properly there need to be practical incentives to “force” compromise, to compel participants to “make deals” to accommodate one another. Those who cooperate to get things done differ from issue to issue, so that there is no permanent majority on all issues. Thus, exclusive groupings tend not to form.

When I studied political science, this was called “brokerage” politics. It led to “big tent” political parties that brought together a wide range of interests. For example, there were “Red Tories” and “Blue Liberals” and pragmatic “Prairie-style NDP’ers,” all of whom had much in common. Within a political party, within a caucus, and within a cabinet, no group could have their way all the time. Pragmatism and moderation were needed in order to get things done.

But, to use Mark Harding’s terminology, when “everything [is] judicialized” and is transformed into a constitutional issue, the final decision-makers become judges, not those who are elected. Court cases tend to be “winner take all” contests. If you can win big in court, why compromise through elected institutions? Indeed, political compromise can be seen as unprincipled when one characterizes issues of public policy as questions of constitutional rights.

But, if we turn away from the practical avenues of political pragmatism into the victory or defeat of litigation as a means to determine public policy, do we not undermine moderation and honourable compromise? That is the concern highlighted with great prescience by Peter Russell. I do not read his critique to be directed against the content of any particular court decisions. Rather, it related to the consequences for the operation of democratic institutions of having more and more public policy determined through the judicial process. Well, what of it?

For those whose views are shaped by post-modernism and critical theory, pragmatism and moderation by elected officials are not virtues. Rather, they are business as usual within a power structure designed to sustain the discrimination and exploitation that pervade our society. In this view, liberal democracy is not a manifestation of freedom. Rather, it is an instrument of repression. That is a dark view of liberal democracy and Canadian society that I do not share. I’m familiar with Habermas and Marcuse. I have read them. I just don’t agree with them. It’s a misconception of society.

My views are akin to those of Cicero, Hanc retinete, quaeso, Quirites, quam vobis tanquam hereditatem, majores vestry reliquerunt: “Preserve, I beseech you, these liberties that your ancestors have left you as an inheritance.” Here I speak figuratively, rather than literally, as the Roman Senate was an assembly of aristocrats, and the liberties of Romans were confined to those who held citizenship. Nonetheless, the figurative point remains; many of the liberties protected by the Charter did not begin in 1982. They were part of our heritage.

In 1872 Benjamin Disraeli, speaking as a partisan, which I do not, contrasted the opposites of a “confederacy of nobles” and a “democratic multitude.” Instead of these opposites, Disraeli spoke of One Nation, “formed from all the numerous classes in the realm—classes…equal before the law, but whose different conditions and different aims give vigour and variety to [the] national life.” This combination, Disraeli concluded, “is the best security for public liberty and good government.” Disraeli while being a “Red Tory” in domestic policy was also an arch-imperialist. Thus, I embrace his words as an expression of domestic purpose, especially as to the obligations of mutual support within society. From that perspective, does not his vision of One Nation continue to embody wisdom, even as the aspirations of that nation change with time?

Over time, liberal democracies are able to understand themselves differently, to adapt, become more inclusive, and aspire to be more just. The structure of our institutions, the principles of our laws, and the good faith of citizens can serve us well as society appreciates new perspectives. Thereby, step by step, meaningful progress can be achieved.

I have confidence in the democratic system. One can readily point to the failings of Canada and other liberal democracies, just as one can readily conceive of utopian alternatives. But what other system has achieved so great a degree of individual liberty, so high a degree of prosperity and so open a system in which to pursue justice?

Thinkers who are critical of contemporary society and who properly call on us to comprehend historic and contemporary injustices can be dismissive of liberal democratic institutions. In their view, how can one value a system under which such wrongs have occurred? And, is it not necessary to create a new system so as to ensure that further wrongs do not occur? To this, my response is that liberal democracy is a vessel that is filled by successive generations with the aspirations of that generation. As those aspirations change so will the outputs of the system.

Ours is a good country, one that warrants our devotion. But such devotion needs to be founded on a mature understanding of history and how people, in all of Canada’s diversity, live today. We should not tell ourselves comforting fairy tales, just as we should avoid empty negative rhetoric. Rather, we should seek to live in an inclusive and fair society, while being practical and realistic.

Recommended for You

The Weekly Wrap: Stop painting Alberta as the villain of Canada

Where the CBC went wrong

The Week in Polling: Majority of Canadians want the Alberta-B.C. pipeline; Optimism about the Carney government drops; 87 percent of Canadians concerned about the state of housing

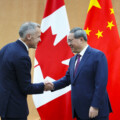

‘An approach that lacks principles’: The Roundtable on Canada’s confusing China reset and the lack of scrutiny on Carney