Secrecy has become a key hallmark of the Trudeau government. From refusing to disclose the legal advice relied upon to invoke the Emergencies Act, to invoking a record number of secret orders in council, to declining to reveal even the existence of colossal contracts, the early promises about a government that would be “open by default” have long since vanished.

It’s been quite the journey.

In 2014, after eight years of the Harper government, Trudeau’s first private member’s bill as an opposition MP, the Transparency Act, offered bold promises to revitalize the access to information systems. More promises followed in the lead-up to the 2015 election. But after eight years of Trudeau’s own government, newly published data on the performance of the access to information system paints the picture of a system in terminal decline.

Those statistics show many federal institutions now regularly fail to answer access to information requests within legally required timelines. For example, Public Services and Procurement Canada, which is under scrutiny for its practices with respect to wasteful third-party consultant contracts, only responded to requests last year within lawfully mandated timeframes 24 percent of the time.

Canadian security and intelligence agencies have promised more transparency. But last year, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service only provided full and unredacted copies of records in 0.3 percent of requests answered. The Communications Security Establishment, which is set to obtain vast and largely unchecked powers through Bill C-26, closed less than one in seven requests within lawful timelines.

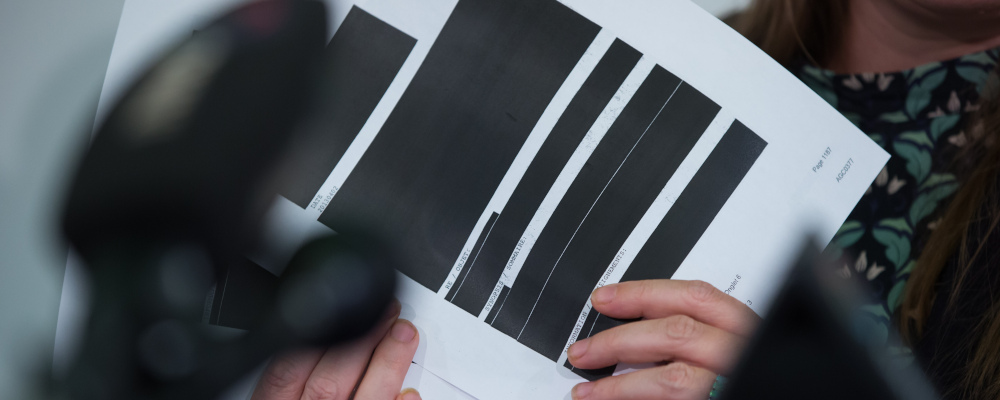

Redactions are a significant problem. The Privy Council Office, which supports the prime minister and cabinet, released 700 records last year but invoked cabinet confidences to redact information 794 times. Under Harper, the Privy Council Office preserved for ten years most records created in the process of responding to access to information requests. Under Trudeau, this document preservation period has been reduced to just two years.

These practices of over-redaction and destruction of documents harm the preservation of Canadian history, contribute to misinformation, and undermine the purpose of our access to information laws—namely, to foster an open and democratic society and to allow public debate on the conduct of our institutions.

The government has cited translation costs as a barrier to putting in the public domain copies of previously released requests. But how often is translation even requested by people using the system? Last year, out of 209,375 requests closed for access to information, there was just one request for translation from English to French. There are no requests at all for translation from French to English.

Funding for the access to information systems remains far too precarious. The budget of the Office of the Information Commissioner, which reviews complaints about the system, is supposed to be independent; but its budget depends on a federal institution, the Treasury Board, that is often the subject of the commissioner’s investigations.

It is no surprise, then, that last year the Treasury Board rejected the commissioner’s requests for more funding to deal with an uptick in complaints. Indeed, last July, the commissioner noted that complaints had grown by 185 percent since she assumed her role in 2018. She has since concluded in her latest Annual Report, “It is clear that improving transparency is not a priority for the government.”

Instead, the government is now teeming with employees who specialize in “communications.” More than 4,000 federal government employees now have that word in their job title. Outside of government, investigative journalist Cecil Rosner estimates that the ratio of public relations consultants to journalists is now 14 to one.

Like the federal government’s penchant for hiring consultants and communication specialists, lawyers have become far too deeply enmeshed in the system. Sustainable Development Technology Canada, which is embroiled in controversy, sought legal advice in a startling 67 percent of the requests it answered last year. The Patented Medicine Prices Review Board did so for 93 percent of requests answered.

These staffing and funding priorities are set against the backdrop of an existential crisis facing Canadian journalism, as detailed in an ongoing series in these pages. As veteran journalist Dean Beeby notes, media have been abandoning access to information systems at provincial and federal levels.

Is that any surprise? The departure from an ethos of “open by default” to one that is closed by design goes to the heart of the government’s credibility problem these days. Broken promises erode trust. New ones fall on skeptical ears.