Most people who bother with the matter at all, to paraphrase George Orwell, would admit that Canadian foreign policy is in a bad way. More than any time in living memory, Ottawa looks completely lost in the world. Its foreign initiatives are disjointed and driven by domestic politics, its adversaries view it as petulant and weak, and, perhaps worst of all, its allies and partners are losing confidence in its capabilities and commitments. The global order is changing rapidly, and Canada seems unwilling or unable to adapt.

Specific policy proposals—for instance, that Canada should finally reach NATO’s 2 percent of GDP defence spending target—skate around the real issue: Ottawa’s seemingly congenital inability to set international priorities and follow through on them. Indeed, while diplomatic and military resources are valuable, policymakers can only determine priorities, navigate trade-offs, and decide which tools to deploy and when, but only if they are equipped by political leaders with clear strategic objectives.

That is how strategy works. And strategic thinking, in turn, requires a realistic assessment of a country’s geopolitical circumstances and national interests. Canada’s profound foreign policy malaise flows, in large part, from its failure to think and act strategically—a consequence of not taking geopolitics seriously. That’s a luxury that Canadians can sadly no longer afford.

For most of Canada’s history, its lack of strategic culture hardly mattered. In fact, it reflected an extraordinarily favourable geopolitical neighbourhood. Only a country as safe as Canada—surrounded by three oceans and a vast Arctic territory, bordered by an economically dynamic and democratic neighbour, and protected by and allied with the world’s leading military powers—could afford to neglect geopolitics. First as part of the British Empire and then under the protective umbrella of the United States, Canada took its national security for granted. Until crises roused it to action, Ottawa could engage with the world largely on its own terms.

But those days are over, and Canada is struggling to adapt to a radically altered geopolitical environment.

First, the international system is being rapidly reshaped—not only by the deepening rivalry between the United States and China, but also by the rogue behaviour of Russia and the rise of regional powers like Brazil, India, and Saudi Arabia, among others, whose economic and strategic weight will only grow over the coming decades. Put simply, international institutions and long-standing diplomatic habits no longer reflect the underlying balance of global power. Geopolitical instability is likely to worsen as great and regional powers jockey for position in an emerging multipolar world order.

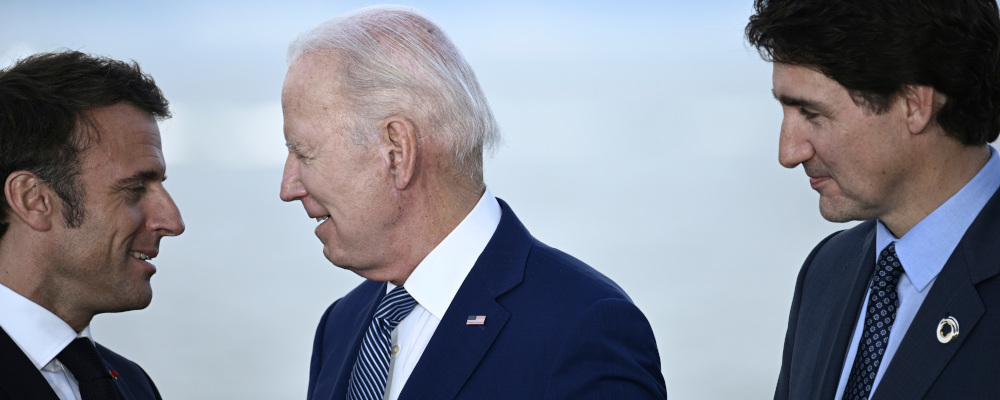

Second, and relatedly, Canada’s closest ally and trading partner, the United States, is no longer the undisputed global leader it was during the “unipolar moment” that followed the Cold War. Although the U.S. will remain by far Canada’s most important bilateral relationship, Ottawa needs to prepare for a more divided and unpredictable neighbour to the south, regardless of who wins this year’s presidential election. Canada’s measly defence spending (just 1.3 percent of GDP in 2022, making it one of the lowest in NATO) will attract increasing negative attention in a Washington focused on strategic competition with China, Russia, and Iran. Future U.S. administrations will be far less polite about subsidizing Canadian national security with American taxpayer dollars.

Third, the great distances and rugged terrain that once insulated Canada from the world are no longer such formidable barriers. Rapid technological advancements—hypersonic missiles, artificial intelligence, and capabilities in the linked domains of cyber and outer space—are revolutionizing the frontiers of national security. Meanwhile, climate change is melting sea ice and fuelling the rapid transition to clean energy technologies—opening the Arctic to shipping, stoking geopolitical rivalries in the region and boosting demand for Canadian critical minerals and other natural resources.

In principle, there is no reason why Canada cannot thrive in this new world, given its many comparative advantages. But parochialism and inertia—a narrowly domestic political focus combined with unthinking and outdated foreign policy habits—are holding Ottawa back from reorienting and revitalizing its international engagement. With the right leadership, however, Ottawa could embrace a more strategic approach to the world, starting with three fundamental changes that together would constitute a foreign policy “Big Bang.”

First, Canada needs a foreign and security policy review. The last official update of Canadian foreign policy was released in 2005, and Ottawa hasn’t published a national security strategy since 2004. Think about how much the world has changed in twenty years, since the aftermath of 11 September 2001. Without an updated, overarching framework that articulates political objectives, matches resources to priorities, and survives changes in government, Canadian policymakers are flying blind.

Piecemeal documents, like the new Indo-Pacific Strategy, are positive steps. But they can’t answer the core strategic question that needs answering: should Ottawa have a truly global policy or one targeted at specific issues or regions? If the former, then diplomatic and military resources must be adequately funded to support it. If the latter, difficult decisions need to be made about Canada’s global footprint. The United Kingdom’s recent Integrated Review, published in 2021 and refreshed in 2023, could serve as an example for a whole-of-government Canadian strategic policy.

Second, although it will take time and commitment, Canada’s national security apparatus needs far-reaching reforms. Recent efforts to spur modernization within the foreign service and Global Affairs Canada more broadly should be commended, supported, and continued.Full disclosure: I served on the independent, external advisory council for the department’s “Future of Diplomacy” initiative Yet revelations over the handling of alleged foreign interference, wasteful defence procurement sagas, and cratering morale in the RCMP and Canadian Armed Forces are indicative of institutions unfit for purpose. This demands attention in the national interest, not partisan point scoring.

Third, Canada should cultivate a deeper and broader foreign policy ecosystem to better utilize its human capital, encompassing academic institutions, think tanks, and Ottawa’s policy community. Too often, Canadians with relevant expertise must look elsewhere (usually the U.S. or U.K.) for careers, and too few specialized university programs—mostly in Ontario and Quebec—send graduates into the public service, reinforcing Ottawa’s narrow Laurentian perspective and limiting its intellectual diversity.

Civil servants, moreover, need opportunities to escape the Ottawa bubble; more external secondments could help refresh their knowledge through policy-relevant research, which would lead to new ideas percolating back into government. And Canada’s multiethnic population means that there are no “far away countries of which we know little”—a potentially huge but still largely untapped advantage in the emerging international order. In short, Canada can no longer afford to punch below its potential in developing and deploying foreign policy talent.

Canadians expect that their leaders should sit at the top tables of global diplomacy. But that is not a God-given right. Geopolitical conditions are changing, and Canada has developed a reputation for failing to put its money where its mouth is—hence growing marginalization in global forums and exclusion from new U.S.-led groups like AUKUS and the Quad. The choice for Canada is stark. Either Ottawa needs to begin to think and act strategically—articulating objectives, deciding on priorities, and funding them appropriately—or it should lower its expectations and adjust to a much-reduced role in the world.

Recommended for You

Ontario’s Progressive Conservatives need a wake-up call

From Jordan Peterson law to bail reform: 9 policy proposals from the Conservative convention that could spur Canada’s comeback

‘A delicate balance’: Why the Conservative convention is a crossroads for the party

Canadian pluralism will fail if the law is not equally enforced