What is the purpose of a public library? It is a local gateway to the world and all the knowledge that it contains. It is a sanctuary of the written word and a cornerstone of civic life and the community it serves. It provides a foundation for lifelong learning, curiosity, and independent critical decision-making, along with the personal, social, and cultural development of individuals and social groups.

Participation in and the development of a robust democracy in a diverse and open liberal society is contingent on unrestricted access to education and knowledge, thought, culture, and information. In engaging with this content, we must have the intellectual freedom to refute, question, and debate topics.

The role of the librarian is a steward and protector of this public space. They must allow for equal access to the knowledge it houses. That knowledge should be eclectic, inspiring, insightful, and provocative.

The wonderful thing about a library is that if you don’t like a particular book, you are not obligated to read it. There are plenty of books to choose from.

This approach to free thought was not the case in the shameful dismissal of Cathy Simpson, chief librarian, and CEO of Niagara-on-the-Lake Public Library. The treatment she endured demonstrates a complete disregard for viewpoint diversity demanded in the forum of the public library.

Simpson wrote a column entitled “Censorship and what we are allowed to read: public libraries should be home to many viewpoints, not just progressive ones” for a local newspaper. It was published, ironically, on February 22nd during the “Freedom to Read Week,” an annual event that encourages Canadians to think about and reaffirm their commitment to intellectual freedom, which they are guaranteed under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. It also happened during the Toronto Public Library’s intellectual freedom series.

It was a column I would have written myself, and I commend her for doing so. In it, she addresses genuine concerns about hidden censorship in libraries that amounts to a selective defence of books and authors based on the valour of victimhood. She also raised the narrowing of book choices which now dare not diverge from what is now deemed absolute truth. If they are questioned, the questioner faces strong political forces that will be out to get them. “Viewpoints that don’t conform to progressive agendas are rarely represented in library collections and anyone who challenges this is labelled a bigot,” she wrote. “We ask our colleagues to ensure ‘Freedom to Read Week’ does not become ‘Freedom to Read What We Decide You Should Read Week.’”

Shortly after Simpson’s article came out, Matthew French, a resident of Niagara-on-the-Lake, wrote a response letter that served anything but an intelligent rebuttal to the views presented. It reads largely like a hit piece designed to cast Mrs. Simpson as persona non grata and damage her emotionally and financially, leaving her reputation in shambles. He implies she’d be open to the discrimination of gay people and denying the Holocaust.

What I find most amusing is that instead of responding to Simpson’s article and presenting arguments, he instead chose to smear her. He actually proved her points by claiming in fact that her balanced views proposing library neutrality and the freedom to read, and her association with the Foundation Against Intolerance and Racism (FAIR), are horrid “far-right” American talking points.

Now, when you think of far-right folks, do you think about people like Shadi Hamid, a respected professor of Islamic studies and Washington Post columnist? How about respected New York University psychologist and author Jonathan Haidt? What about Daryl Davis who is a musician, author, actor, and lecturer noted for “having interviewed hundreds of KKK members and other white supremacists and influencing many of them to renounce their racist ideology”? Davis is a Black man, by the way.

Or wait, maybe you think of someone like Andrew Sullivan. He’s a writer, blogger, and author whose 1989 landmark essay “Here Comes The Groom,” made the first real case to conservatives for gay marriage in the U.S.. He was an influential force in the American Supreme Court’s decision to legalize gay marriage less than four decades later. He’s also gay. All these people sit on FAIR’s board of advisors.

Or maybe you think of someone like Monica Harris who is an activist, lawyer who graduated from Harvard and worked with Barack Obama, and author who “advocates for balanced, common-sense solutions to systemic problems based on our shared values and goals.” She is a gay Black woman. She’s also the executive director of FAIR.

I find it frightening yet unsurprising that Simpson’s article, which calls for a return to liberalism, was labelled as “right-wing dog whistles” because it did not adhere to the current tribal doctrines whereby you must give absolute obedience to one side.

We now live in a world where these sides of the political spectrum have drifted to become so far apart from one another; where any deviation of thought from either side’s tribal doctrine is seen as “extreme,” and where the person who espouses it must be branded as an undesirable and banished from the public square. The letter that French wrote was just that: a signal of absolute obedience to his tribe, and an effort to brand Simpson as an undesirable who must be banished.

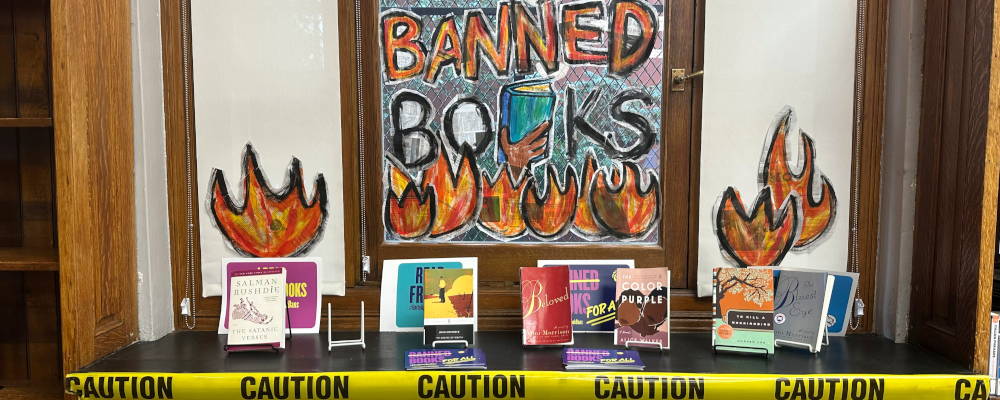

We are living in a world where books, authors, and even librarians are being removed because they do not ascribe to the absolutist ideas of the Right and Left; where you must obey the sacred tenets of your “side” or “tribe.” Attempts to ban and censor have become mainstream.

Over the years, in our Canadian school libraries and public libraries, books such as The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank, To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood, Maus by Art Spiegelman, Underground To Canada by Barbara Smucker, The Wars by Timothy Findley, The Golden Compass by Philip Pullman, Salma Writes a Book by Danny Ramadan have all been the targets of some form of censorship and calls for removal. Some are still being targeted today.

Books are art. So, like any piece of art, there will be people who are going to like them and people who won’t. However, that doesn’t mean that we must then not make it available to everybody else. If we start removing works deemed controversial because of their themes or their authors from the shelves of public libraries, school libraries, and bookstores, then we are restricting people’s ability to engage with those topics. We are depriving them of topics that challenge their perspectives; topics beyond the ones that make them feel comfortable.

Recommended for You

David Polansky: Kind, tolerant Canada is failing the antisemitism test

Paul W. Bennett: With AI taking over classrooms, it’s time to go old school again

‘I want images of burning’: The Full Press on how bias infects protest coverage

Stephen Staley: Andor and the politics of despair