In The Weekly Wrap Sean Speer, our editor-at-large, analyses for Hub subscribers the big stories shaping politics, policy, and the economy in the week that was.

The post-budget bump that never was

If The Hub community wants to understand the overall reaction to last week’s federal budget, it doesn’t need to rely just on polling—which, by the way, is universally negative.

Another means to understand both the underwhelming budget and the government’s deeper political challenges is the uncharacteristically strident response from many industry associations, stakeholder groups, and policy experts.

Let me step back for a minute. There’s generally a tendency in Ottawa for these adjacent policy organizations and voices to constrain their criticism of the government because their long-term interests depend in large part on a constructive two-way relationship. This is particularly true for industries or non-profit groups that disproportionately rely on government funding or regulatory policies for their ultimate success.

It means that whatever its short-term policies, it’s rarely worthwhile for individuals or interest groups to burn bridges with a government. There are exceptions of course. Sometimes governments enact policies that are so injurious to a company, industry, or stakeholder group that they cannot turn the other cheek. The Harper government’s income trusts decision is one example. The Trudeau government’s emissions cap on the oil and gas sector is another. But these extraordinary cases aren’t the norm.

What’s interesting, however, about the post-budget reaction from various groups, including the investment community concerning the capital gains tax hike (discussed in more detail below) or the disability community concerning the disappointing Canada Disability Benefit, is that they’ve been prepared to go much further in their criticism than is typically the case.

One explanation is that these policy decisions are indeed so contrary to the interests of these groups that they had no choice but to respond vociferously. Dr. Michael Prince for instance seems to have resigned from the government’s Disability Advisory Panel as a genuine matter of principle because the Canada Disability Benefit failed to live up to the community’s expectations.

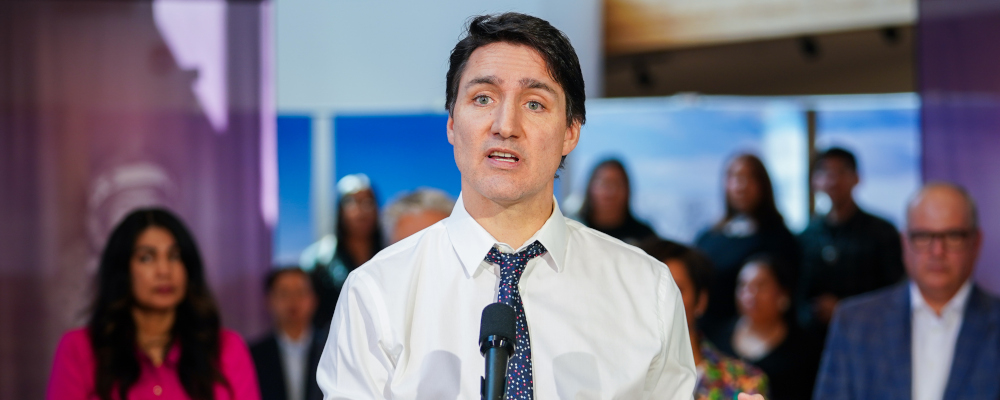

But another—and I think better—explanation is that the highly negative reaction to the budget in most cases isn’t merely about the budget and its measures themselves. It reflects a gradual aversion to the Trudeau government and its policies that’s built up over time but hadn’t yet found expression. The growing likelihood of the government’s defeat in the next election has finally given license to these groups and voices to express themselves. Put differently: the political cost of calling out an irredeemable government has fundamentally changed.

From this point of view, the strident reaction to particular parts of the budget, which may seem somewhat disproportionate, is actually a cumulative aversion to the Trudeau government and its policies. As these political incentives have shifted, what we’re actually hearing is long-standing grievances about the government’s policy approach that individuals and interest groups are no longer self-conscious about communicating. In fact, the Trudeau government’s poor political standing has been liberating for them.

To the extent that this theory is right, it suggests that the people and groups who sit adjacent to federal politics have decided that the Trudeau government is effectively done. That might ultimately prove more revealing than the polling over the past week.

What happens when the wedge issues no longer work?

Last week’s Weekly Wrap described the federal budget’s hike on capital gains taxes as an act of “class warfare.” The prime minister’s post-budget comments about the so-called “ultra-wealthy” were representative of the government’s efforts to use the tax change as a political wedge.

I admit that I assumed it would probably work. Although I’ve previously cited evidence that Canadians are more motivated by concerns about a level playing field than equal outcomes, there’s also reason to believe, based on polling, that they’re prepared to support higher taxes on investors and high-income earners.

The past week or so, therefore, has been heartening. The negative reaction from doctors, entrepreneurs, small businessowners, and a lot of policy voices has been rather overwhelming, and polling tells us that Canadians writ large are similarly skeptical.

This is a big deal. In today’s more populist political environment, it was reasonable for the government to assume that class warfare politics would work. Yet it hasn’t.

It prompts the question: why not? I think there are three explanations.

First, such a major policy change this late into a government’s time in office risks appearing inherently cynical. If this was such a source of fundamental unfairness, why did it take nearly nine years to fix? The prime minister’s self-evidently ardent interest in provoking a fight with the Conservatives and parts of the business community over it hasn’t helped answer this question. Instead, it’s contributed to a sense that the government is now desperate and prepared to manufacture political controversies to try to reverse its declining political standing.

Second, Canadians are increasingly aware of the magnitude of the economic challenges facing the country—namely, economic stagnation, low business investment, and poor productivity—and instinctively understand that a tax on capital will worsen rather than improve them. You don’t solve a national economic emergency or overcome a “lost decade” by penalizing capital.

Third, a lot of Canadians aspire to own assets so even if they’re not affected by the tax hike in the short term, they hope to be over the long term. One poll for instance found that a majority of respondents anticipated that they’d be affected at some point. They ultimately envision becoming part of the “ownership class” and are averse to government policies that stand in their way.

The world of public policy and political ideas typically involves small victories. Although big wins—like the free-market revolution of the early 1980s—can happen, they’re usually rare. The underwhelming reaction to the capital gains tax hike is a small victory. But what makes it so heartening is that it portends a broader, possibly bigger, intellectual victory in which Canadians reject the recent rise of big government and its seeming hostility to individual achievement and success.

Alberta’s energetic exceptionalism is alive and well

Rudyard Griffiths and I spent most of the week traveling across western Canada to meet with current and prospective Hub community members. We spent two nights in Calgary, including a great dinner with roughly 75 business and civic leaders, and I’m now writing the Weekly Wrap from Vancouver.

It’s always nice to come out to this part of the country. The landscape is beautiful and the people are kind and interesting.

What was most striking about our trip though is the renewed energy and dynamism in Calgary. The city went through a difficult half-decade or so, but it’s come out the other side with the same entrepreneurial spirit that has long defined it.

Although regional differences can be somewhat overstated, there is something to Calgary exceptionalism, or what Jason Kenney and now Danielle Smith refer to as “the Alberta Advantage.”

There’s a powerful self-selection bias of the people who grow up or move there. It causes the city to feel a bit more egalitarian and industrious than other parts of the country. Its private sector is just a bit more risk-taking and competitive. Its political economy tilts a little more in the direction of free markets and away from government preferences.

In sum: it stands in some contrast with the more oligopolistic and state-preferenced market structure that one finds in central Canada—an economic model that we’ve previously criticized as “Laurentian capitalism.”

It will be good to get home to see our families and sleep in our beds. But it’s been a great trip. And a key reason is that it’s not only been nice to get a first-hand view of Calgary’s resurgence but also to be reassured that its exceptionalism remains intact.