DeepDives is a bi-weekly essay series exploring key issues related to the economy. The goal of the series is to provide Hub readers with original analysis of the economic trends and ideas that are shaping this high stakes moment for Canadian productivity, prosperity, and economic wellbeing. The series features the writing of leading academics, area experts and policy practitioners. The DeepDives series is made possible thanks to the ongoing support of Centre for Civic Engagement.

It’s increasingly recognized in policy and political circles that one of the biggest challenges facing the country is economic stagnation and declining living standards. This has led policy scholars to try to understand the causes and sources of Canada’s economic malaise.

New research by Macdonald-Laurier Institute fellow Heather Exner-Pirot points to challenges in Canada’s natural resource sector as a “smoking gun.” Her basic insight is that a combination of economic forces and policy-induced harms have undermined what her colleagues Philip Cross and Jack Mintz have characterized as the country’s “golden goose” and that this has significant explanatory power for the overall decline in business investment, productivity, and economic activity.

The purpose of this DeepDive is to test that hypothesis. It aims to understand the economic importance of Canada’s natural resource sector and the extent to which the headwinds that it has faced over the past several years have contributed to the country’s “lost decade.”

As part of this analysis, we also examine the factors—including the role of government policy—that have impeded the natural resource sector’s ability to contribute to more economic growth and higher living standards for Canadians.

Canada’s natural resource endowment

Canadian economic history is replete with an understanding of the disproportionate role of our natural resource endowment. From the fur trade to the “staples thesis,” scholars have put natural resources at the centre of their conception of Canada’s political economy.

Not everyone of course has viewed the outsized role of natural resources in favourable terms. The notion of “hewers of wood and drawers of water” is often characterized as a sign of failure. It represents a squandered opportunity on the part of Canada to transition to what are sometimes perceived as higher-value sectors. One can find plenty of evidence of policy scholars and political actors lamenting Canada’s so-called “resource curse.”

In 2016, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, for instance, told the World Economic Forum: “My predecessor wanted you to know Canada for its resources. Well, I want you to know Canadians for our resourcefulness.”

Cardus Institute scholar Brian Dijkema has challenged this line of thinking as misguided and harmful to Canada’s economic interests. As he and a co-author have written:

We need to stop thinking that being “hewers of wood and drawers of water” is something to be self-conscious about and start seeing it as the source of Canada’s global advantage. In fact, hewing wood and drawing water has…helped to turn Canada into a land flowing with milk and honey that continues to attract people from all over the world.

Dijkema’s characterization is backed up by the data. Across a number of key economic metrics— including economic activity, employment, income, investment, productivity, and exports—Canada’s natural resources are a huge economic asset.

The challenges that the sector has faced over the past several years—including as a result of specific government policies—are a key contributor to Canada’s overall economic malaise. The inverse therefore is also true: boosting our natural resourcesThe definition of natural resources used throughout the DeepDive follows recent work by Cross and Mintz, unless otherwise specified. That is to say, the natural resource sector constitutes agriculture, forestry, fishing, mining, utilities, pipelines, and manufacturers using natural resources for at least 17 percent or more of all inputs. This definition is quite expansive and at points the DeepDive zooms in on certain critical components of the natural resource definition. could have positive economy-wide effects.

The economic benefits of natural resources

Economic activity

The natural resource sector is a major driver of Canada’s economic activity. In 2019, according to estimates by Cross and Mintz, natural resources accounted for 14.9 percent of Canada’s gross domestic product. This percentage has fallen in recent years, after peaking in 2008 at 19.5 percent, when the commodity cycle crashed in 2014-15.

Using the 2019 estimates, the oil and gas subsector was the largest overall contributor to the natural resource sector’s economic output, accounting for 28 percent of the sector’s total economic contribution. Mining accounted for roughly 10 percent of the natural resource sector’s output, with agriculture, forestry, and fishing adding another 12 percent. The remainder of the sector’s economic contributions are derived from utilities, resource-intensive manufacturing, and pipeline transport.

Overall, what is clear is that notwithstanding the 2014-15 drop in commodity prices and the harms to the sector from government policy, natural resource development continues to be a major source of economic output in Canada.

Employment

When considering the sector’s employment impact, we use a slightly truncated definition of natural resources to utilize an existing Statistics Canada dataset that better allows for inter-provincial comparisons.

Overall, in 2021, natural resources employment totaled almost 920,000 jobs, or about 5.6 percent of total Canadian employment. Canada’s four largest provinces account for 86.5 percent of employment in the natural resource sector. Ontario leads the way with over 280,000 jobs, followed by Quebec with almost 200,000, Alberta with almost 190,000, and BC with almost 120,000.

Not only is the natural resource sector a major source of total employment, but the distribution of its employment is highly advantageous too. The geographical distribution of natural resource jobs diverges from the concentration of employment in a small number of major Canadian cities. In fact, a 2021 Natural Resources Canada report found that in more than 1,800 rural and remote communities across Canada, most of which have populations of 10,000 or less, an average of 30 percent of jobs in those communities were dependent on the natural resource sector.

Mineral deposits, managed forests, and oil and gas reservoirs are dispersed across the country and generally located near rural and remote communities. Take the oil and gas sector for instance. It is present in Newfoundland, southwestern Ontario, Alberta, and Saskatchewan, as well as potentially in the Arctic. This provides well-compensated employment opportunities for those who want to remain in or closer to their own communities.

Natural resources also employ people across the skills distribution, including large numbers without post-secondary credentials. In fact, more than 40 percent of those employed in the sector in 2021 had a high school diploma or less.

As other parts of the economy have gone through a process of “job polarization” in which demand for mid-skilled workers has fallen significantly, the natural resource sector has protected Canada from middle-class erosion experienced elsewhere. Its sustained labour demand for well-paid upstream oil and gas roughnecks, forest managers, and mining technicians working in the field and midstream locations has been identified by University of British Columbia economist Kevin Milligan as responsible for “sustaining Canada’s middle class.”

Incomes

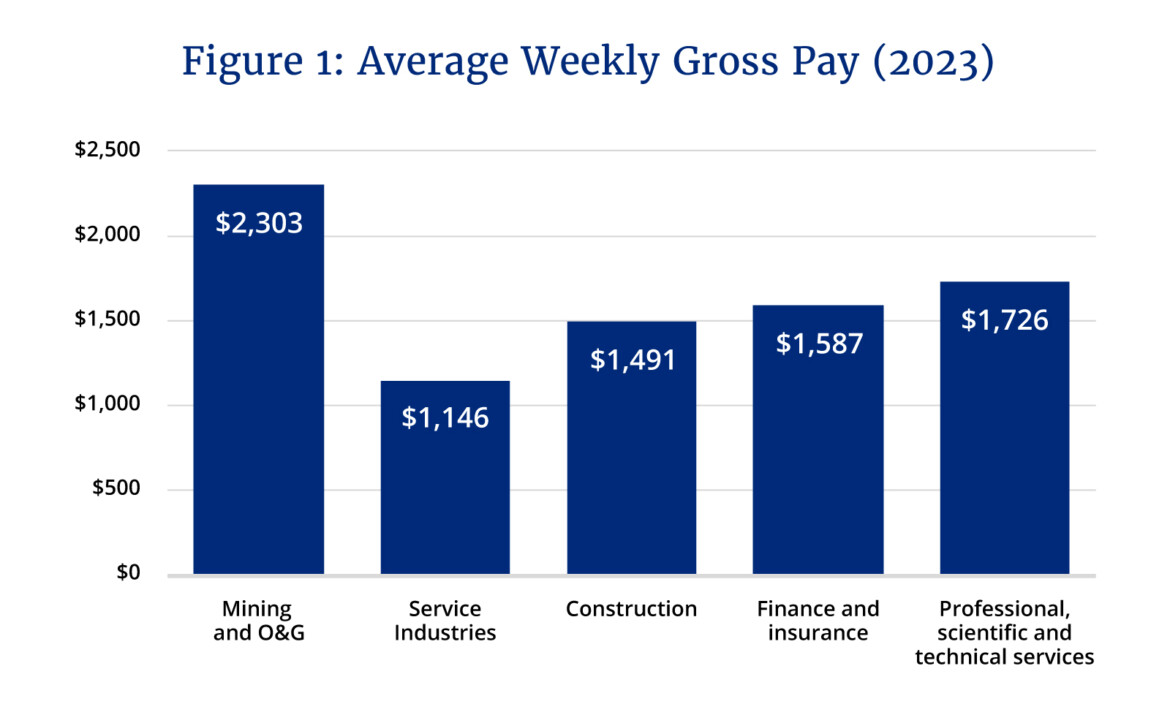

Incomes are higher in the natural resource sector than most other parts of the economy. The average gross weekly pay in the mining and oil and gas sectors has been consistently the highest in Canada since 2007. As seen in Figure 1, the average weekly salary of $2,302.94 is double that of the average service worker ($1,145.63) and is even more than the average in professional services, finance, or health care.

The natural resource sector’s wage premium has been especially beneficial to Indigenous Canadians. Indigenous workers in the mining and oil gas sectors have the highest median income of their peers by more than double ($99,000 versus $41,000).

According to the Indigenous Resource Network, the Indigenous workforce in forestry, mining, and oil and gas is higher than its overall share of the population and quite a bit higher than the percentage in the federal government (see Figure 2).

Investment

Natural resources also dominate Canadian overall business investment. In 2023, capital investments in the natural resources sector were estimated to amount to $109.0 billion or 43.6 percent of all business investment in tangible assets such as structures, machinery, and equipment. At the height of the commodity cycle that coincided with a large upswing in the sector’s capital expenditures, natural resources accounted for as high as nearly 60 percent of all business investment in 2014.

As of 2023, energy accounted for over 60 percent of the sector’s total business investment, down from 80 percent in 2014. While energy’s share of sector business investment may be falling, investment has continued to rise in mining and utilities, as those subsectors expand their capital outlays to keep up with heightened demand from growing electrification efforts.

Productivity

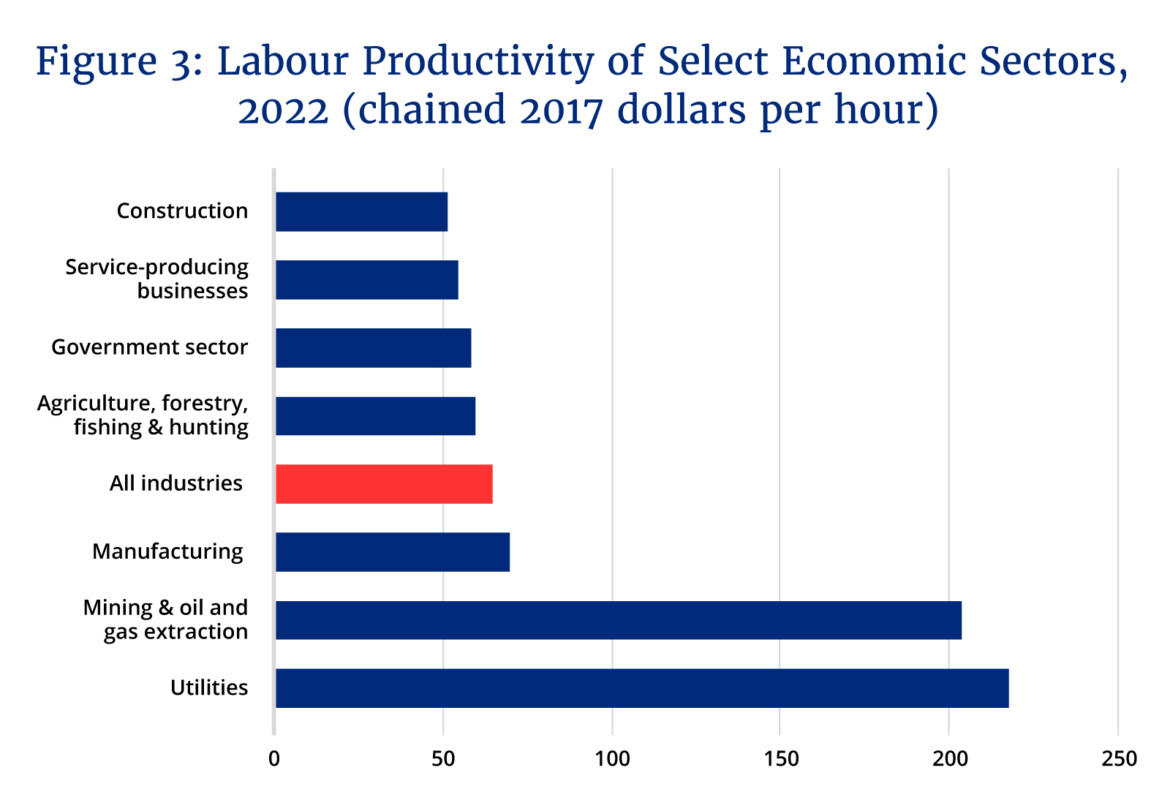

Although Canada is in the midst of a productivity crisis in overall terms, the natural resource sector is something of an outlier. Mining and oil and gas extraction, as well as utilities, are some of Canada’s most productive industries, measured as real output per hour worked. Using data from Statistics Canada, figure 3 shows that labour productivity in the mining and oil and gas extraction sectors is more than three times greater than the all-industry average and almost three-and-a-half times greater than the government sector.

Exports

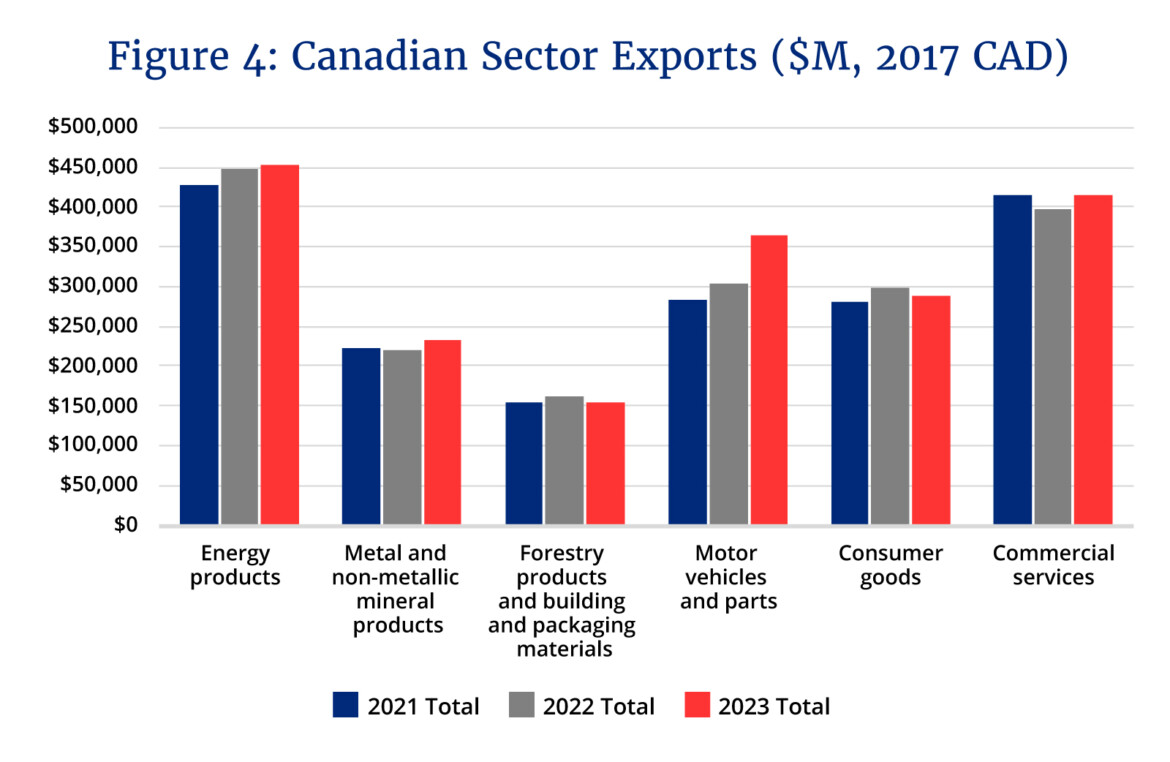

Energy products alone are Canada’s most lucrative export sector, outearning every other subsector, including, for instance, commercial services and motor vehicles (see Figure 4). Added together with mining and forestry, these three natural resource subsectors have made up about 30 percent of total exports since 2017. They are critical building blocks of a stable Canadian economy. Additionally, they offer a unique geographic-based value proposition because they cannot be outsourced to other countries. The resources and the operations to extract them must be located in Canada because the deposits are here. In an increasingly globalized world, this is a true advantage to building a strong domestic economy.

The key takeaway here is that across a number of key economic metrics—including economic activity, employment, income, investment, productivity, and exports—the natural resource sector is a huge economic asset. Even as it has faced headwinds (discussed below in more detail) it has generally outperformed other parts of the economy. It stands to reason, therefore,that if Canada has a more hospitable policy environment for natural resources, then they can play a key role in boosting overall economic output.

Challenges facing the natural resources sector

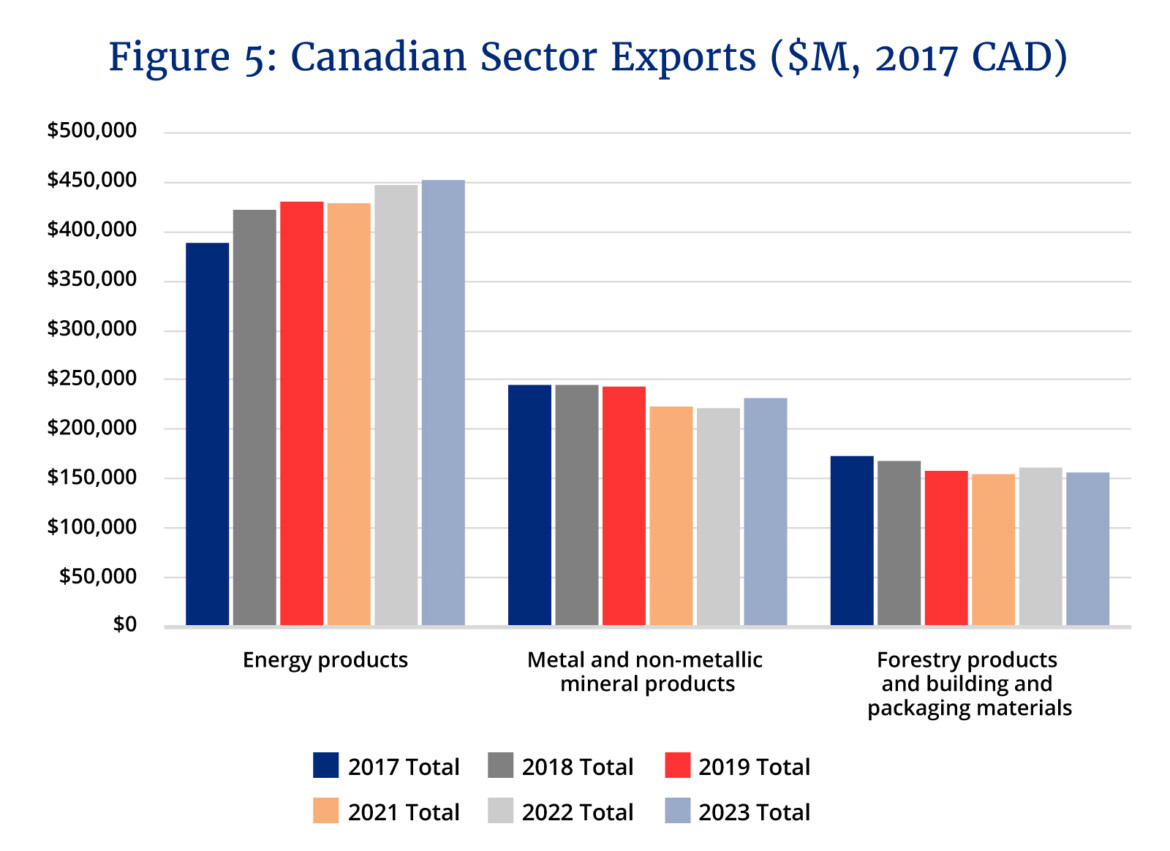

If the natural resource sector is the main engine of the Canadian economy, it has not been firing on all cylinders. Since 2015, for instance, natural resource exports have actually shrunk in real terms (see Figure 5). Oil and gas exports have decreased by as much as 13 percent. Mining and forestry exports shrunk by 5 percent and 2 percent respectively.

Similarly, while the sector remains a major source of business investment, it has experienced a decline itself over the past several years. As Tyler Meredith, a former adviser to Prime Minister Trudeau, noted in a previous Hub essay, resource investment actually fell between 2014 and 2022 by as much as $52 billion. Today annual investment in mining and oil and gas is about half the level that it was during the Harper government.

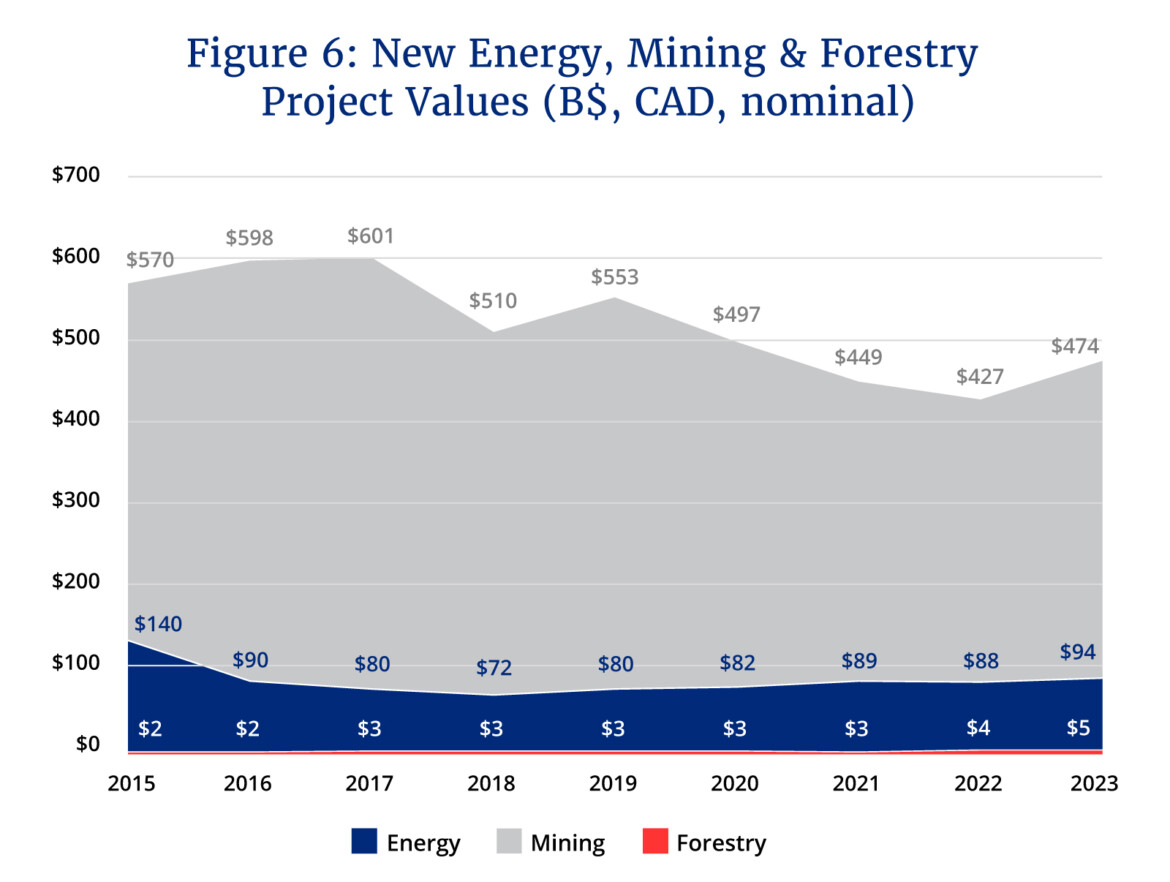

One way to understand these developments is to compare the value of major resource projects planned or underway in Canada since the Trudeau government was first elected. According to the government’s own Major Project Inventory, in 2015, the total projected value of Canada’s next decade of resource projects was $712 billion. As of 2023, it stands nominally at $572 billion, representing a drop of $150 billion (see Figure 6). In real terms, it amounts to a decline from $712 billion to $454 billion—or $258 billion in eight years.

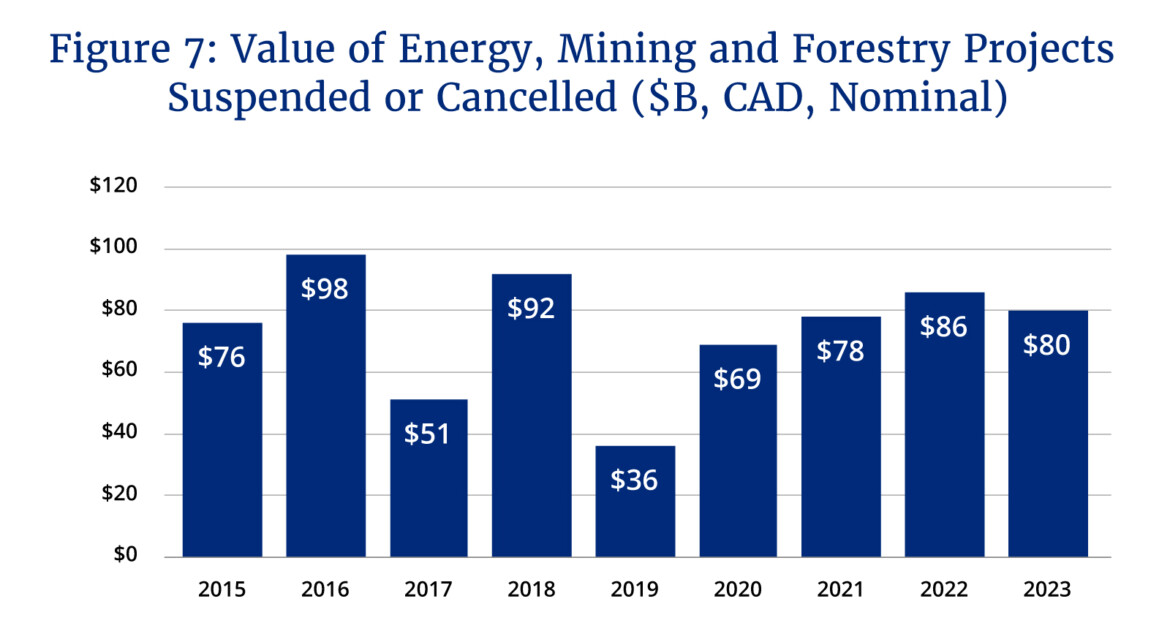

The trend is similar when one examines the number of canceled projects. As Figure 7 shows, since 2015, Canada has seen nearly $670 billion in natural resources projects suspended or canceled. If even 21 percent of the value of these failed projects had been realized, the nominal investment loss would have been eliminated.

It prompts the question: what is happening?

Economic factors—namely the commodity downturn in 2014-15—are a big part of the story. Research by the Bank of Canada finds that the decline in oil prices that began in 2014 and persisted until 2022 had significant effects on the sector and the economy as a whole. There is no doubt for instance that it had a negative effect on resource investment and employment.

But it would be wrong to assume that the challenges facing the sector have been limited to exogenous factors. Government policy has played a role too.

As Exner-Pirot outlines, the Trudeau government has enacted a series of policies that have harmed the investment climate for resource projects. These include: The Impact Assessment Act, which further inserted the federal government into resource project approvals, the oil tanker moratorium, the moratorium on offshore Arctic oil and gas licensing, industrial carbon pricing, the UNDRIP Action Plan, rejection of the Northern Gateway pipeline, methane regulations, Clean Fuel Regulations, the proposed Clean Electricity Standard, and now the proposed emissions cap for the oil and gas sector.

Evidence from the Fraser Institute’s latest survey of energy sector executives indicates that these policies have had a deleterious effect on the investment climate by raising costs and contributing to policy uncertainty.

The emissions cap is a good example. This is a policy that specifically targets Canada’s biggest source of exports with greater regulatory stringency than any other part of the economy. Separate analysis by Public Policy Forum fellow Don Wright and University of Calgary economist Trevor Tombe finds that such a policy will come with significant economic costs—including in Tombe’s case an estimate that the costs will extend beyond the oil and gas-producing provinces.

Key takeaways

The evidence is rather clear that being a “hewer of wood and drawer of water” has produced positive economic outcomes for Canada. The natural resource sector—including forestry, mining, and oil and gas—is a major source of employment, investment, and economic output. It is also more productive than other parts of the economy and is the source of well-paying jobs for people and places that are less represented in other sectors.

Yet notwithstanding the sector’s major contributions to Canada’s overall economy, it has faced headwinds over the past decade or so that have held it back. A major one is the end of a commodity supercycle in 2014-15 that put downward pressure on investment and employment for a near decade. The good news is that these exogenous forces have since dissipated and, as Exner Pirot highlights, we seem to be moving into a prolonged bull market for commodities.

Canada’s ability to leverage growing global demand will require overcoming the second challenge facing the sector: harmful government policy. The past decade has witnessed a cumulative burden of regulations and other policies on our natural resources that have produced significant opportunity costs.

At a time when policymakers are concerned with boosting economic growth and Canadian living standards, it stands to reason that one of the most impactful steps that they could take is unleashing the natural resource sector. As Exner-Pirot rightly concludes:

Bright spots in the natural resource sector’s performance have mostly been despite, rather than because of, federal government policy. As we move into a prolonged bull market for commodities, the entreaties of the last century should be heeded. Let us celebrate and support our resource and energy sector with good, common sense policy. When we do, it can provide an incredible foundation for growth, productivity, security, and prosperity for all Canadians.

Recommended for You

‘It’s jarring’: Hub Politics on how Canadians are reacting to Trump’s foreign policy moves

The global policeman is becoming the global rent-seeker

An Alberta budget crisis? It may be closer than you think

Trump’s new ‘Donroe Doctrine’ leaves no room for Carney’s China reset