When times are tough—and today feels a lot like that—there are many myths we tell ourselves. “People are leaving in droves. It is impossible to get ahead. We are not productive the way we once were.”

Except, in the objective reality in which facts exist, most of those statements are wrong. Not just a bit wrong, decidedly wrong. There are certainly kernels of truth on which such narratives of brokenness and despair are built, but the truth is not so stark.

Since the notion of Canada being “broken” is often attributed to Justin Trudeau, I want to assess these claims in the context of how different things are today compared to when his predecessor, Stephen Harper, was in office.

On the economy, the current occupant of Rideau Cottage has a fairly strong record that has steered Canada through a commodities recession; an unprecedented and unprovoked trade war with our closest ally and largest export market, the United States; and the largest economic and public health emergency in a century.

Unemployment is near record lows. The share of Canadians of core working age (between 25 and 54) who are attached to the job market is up more than 3 percentage points, after stagnating for decades (figure 1).

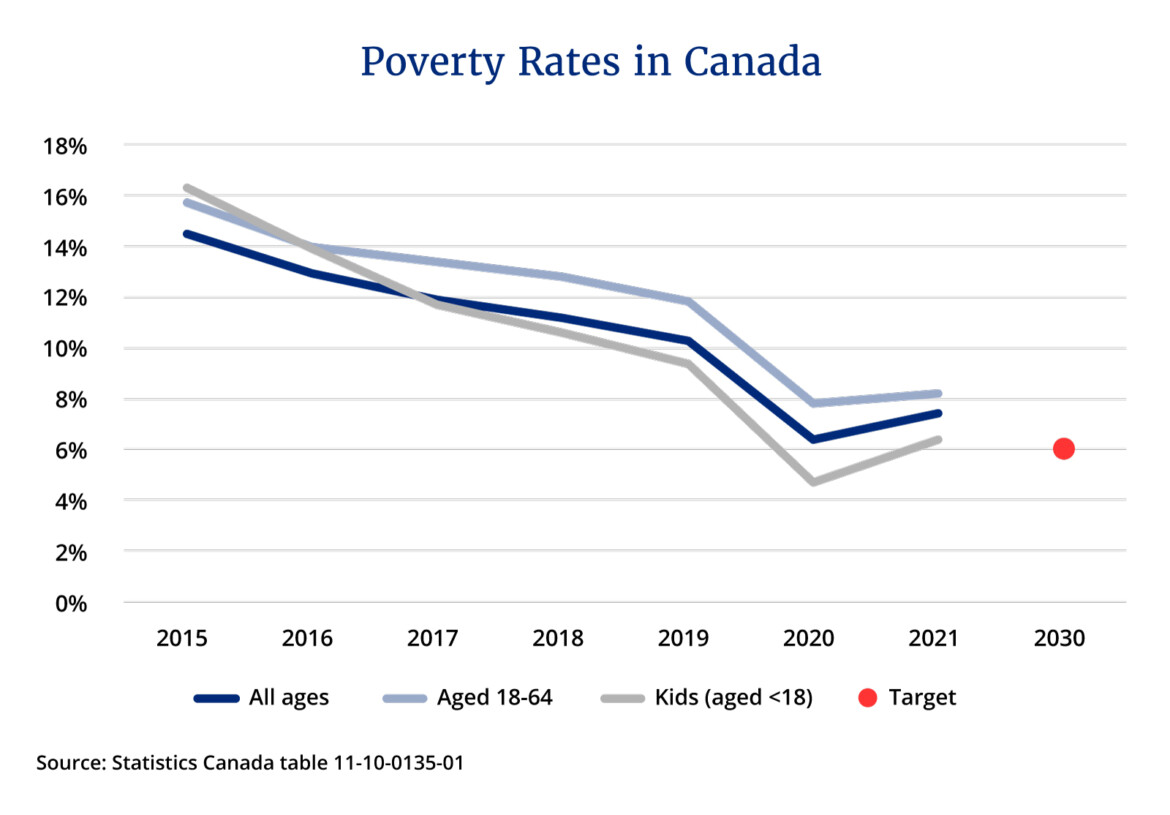

And, consequently, incomes have accelerated and poverty rates have been cut in half (figure 2).

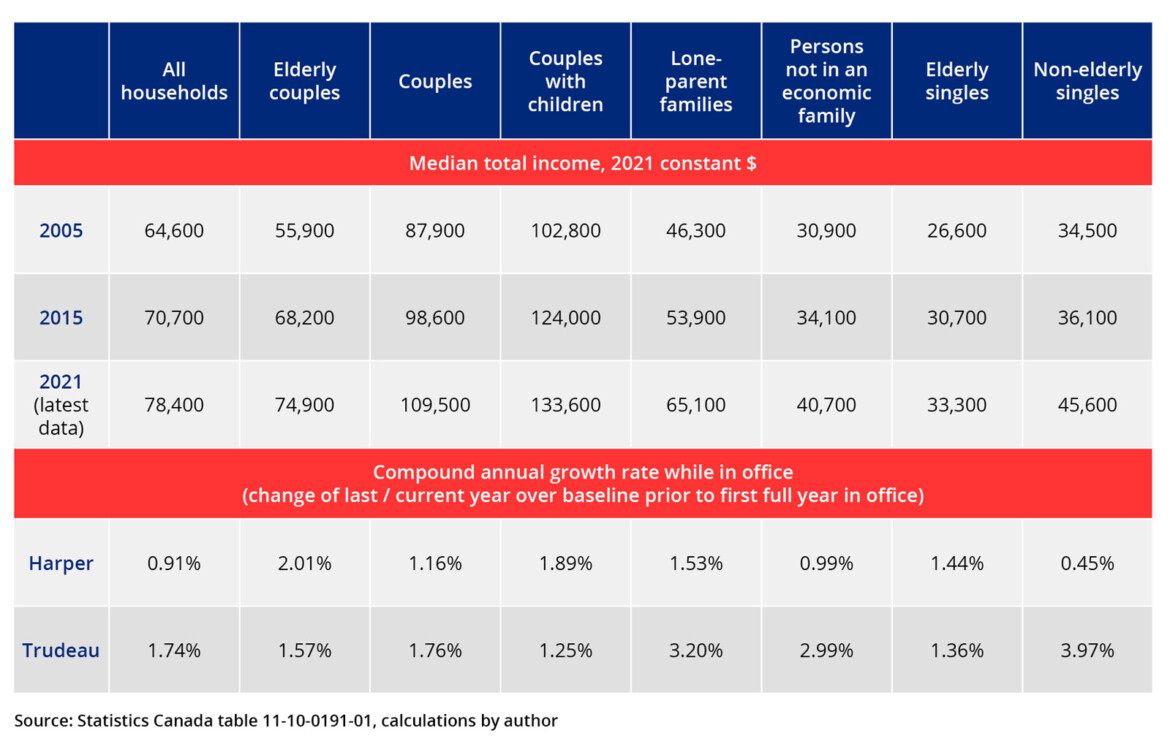

This becomes clearer when we break these statistics down at the household level (figure 3). The median total income among all households has risen at almost double the rate—in real, inflation-adjusted terms—under Trudeau compared to Harper. The following table compares compound annual growth rates, meaning we can isolate the general trend across the various business cycles and time periods in which they were each in office.

While this data ends in 2021 (thanks to administrative tax data that is still being finalized), the micro and the macro picture reinforce each other: more people are working, leading to lower poverty, and higher incomes. This is what progressive economics ought to look like.

The impact is starkest among both single parents with kids and non-elderly single individuals (in part due to the significant impact of CERB during COVID-19), where real median income grew, respectively, at twice and nearly seven times the rate under Harper.

These statistics mean something tangible and transformative in the lives of people.

Sean Speer and Livio Di Matteo have recently argued in these pages that Justin Trudeau’s economic agenda has been one of extensive economic growth (buying growth) versus intensive economic growth (higher levels of wealth). The data presented above stands in contrast to this claim—more people are working, and earning higher income. While it is true that income transfers, such as the Canada Child Benefit, and a national early learning and child-care program, have played a big role in supporting these gains—that is the point. Extensive growth can be used to support intensive growth.

As a result of targeted and impactful investments, the effect of a 3 percentage point increase in the employment rate among working-age adults is that among a population base of 28.2 million persons in this age group, that translates to nearly 850,000 more people who otherwise have a job than would be the case if the employment rate at the start and end of Harper’s time in office prevailed today.

And child care will likely increase this number over time. It is Justin Trudeau, not a Conservative prime minister, who has created the hope, dignity, and opportunity that comes with a solid income.

But as much as these statistics are encouraging, it is also obvious that a good-paying job may not seem like something redeeming when costs are rising, our public health system is under strain and we live in a polycrisis of wars and catastrophic weather events.

Many people feel dispirited. As reported in our recent MB Policy/Abacus Data poll nearly two in three Canadians think Canada is headed on the wrong track.

But that isn’t the question. The question is whether, in the words of Pierre Polievre, Canada is “broken”?

A country that is broken is not one where jobs pay more, more people want to and do work, and where poverty is down.

A country that is broken is not one that ranks among the top in the world as the most desirable place to live.

Like many countries, we have our share of problems. And many of the problems plaguing us are the same ones plaguing our neighbours in the global community.

In a world in which there are an ever-mounting number of crises, we have to be clear about what needs fixing and what does not. There are two problems I would suggest that need careful attention.

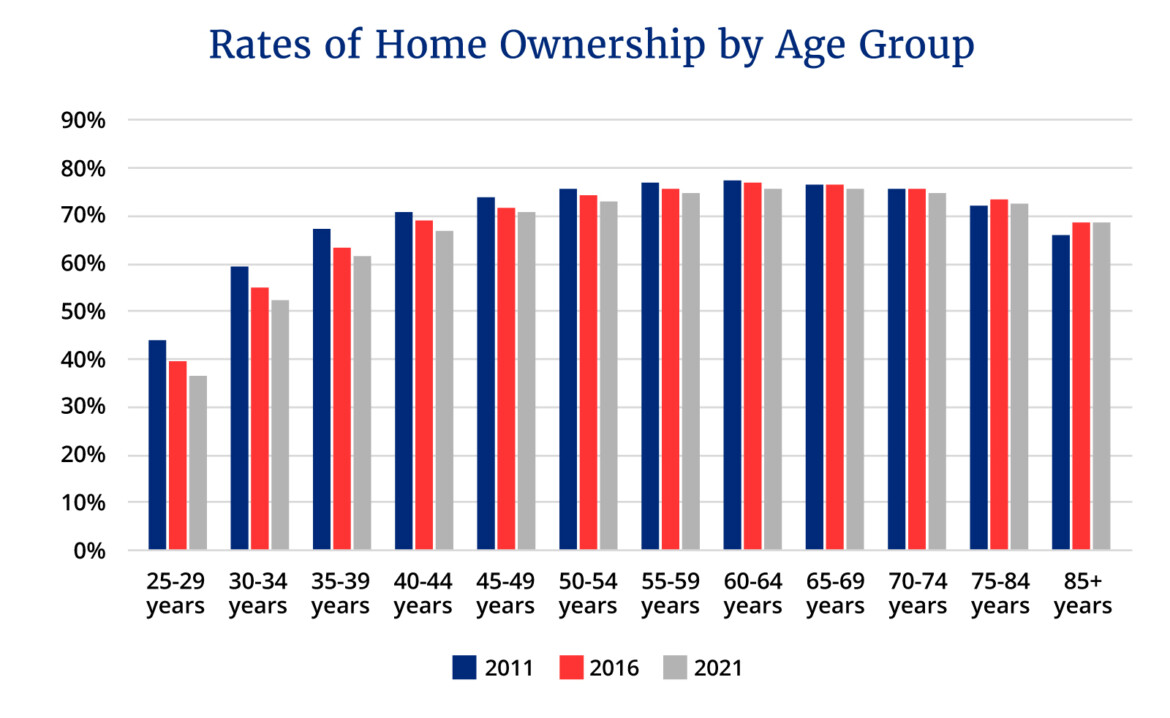

First, the rate of housing ownership is falling among younger cohorts (figure 4). Despite good-paying jobs, the rising cost of housing is a real, intergenerational problem. One that goes back decades thanks to disinvestment in affordable housing and poor urban and population planning policies on the part of multiple levels of government. We need to give young people a path to affordable home ownership—or at least have a real, societal reckoning about the sociological stigma associated with renting. Leaders at all levels are starting to act with ambition, but more is needed.

Fig. 4. Graphic credit Janice Nelson.

Second, Canada’s capital investment base is hurting. It experienced a major trauma during the 2014 commodities recession and has not fully adjusted for the structural changes that period brought about. While much has been said about real GDP per capita, this statistic is meaningless in terms of future growth since it simply tells us about how a mythical pie is shared in ways that are not actually real.

Our overall capital stock—the collective value of the physical and intangible things we build as assets—is what drives our ability to create higher rates of growth over time. That growth is what eventually goes to pay for higher wages and bring down inflation with greater capacity and supply.

Since 2014 investment in non-residential capital has decreased in real dollar terms by $26 billion (figure 5). All of that—and then some—can be attributed to the significant decline in investment in Canada’s resource sector. In the year before Harper left office, just as commodity prices peaked and then began to drop, miners and oil and gas producers invested over $100 billion in capital projects. Today, that number is half what it was.

Fig 5. Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Contrary to popular belief in some circles of discourse online, this is not a problem brought on by neglect by our leaders. In fact, our leaders have been wracking their collective brains for the last decade about how to respond.

Over that time, governments at all levels and led by all major parties, instituted a buffet of investment incentives to help spur new activity across all industries, including enabling businesses to fully write off the cost of building a new production facility. Government itself has also stepped in and significantly increased its own investment in infrastructure, offsetting about 20 percent of the drop in the resource sector.

And yet this problem persists.

This is fundamentally a business problem, but that is not how it is often framed by our policy elites who like to lay the blame for all problems at government. And to a certain extent, it is a global problem, induced in part by long-term changes in how and where we get and develop our energy.

The breakdown of the capital investment cycle puts at risk future jobs and opportunities, particularly for the middle class and those for whom a university education is not of interest.

Yet none of that is what we hear from the nattering nabobs who constantly say Canada is broken.

If we have a problem it is that we are not focused on the right problems, with the right mindset. Canada is a place of hope and ingenuity. If we are to deploy the creativity and talent we need in the future to tackle the big problems we face, we need leadership that will bring us together. Not reflect back to us a distorted image of what ails us in order to foment populist angst for its own sake.