The news media in Canada is in crisis. Policy responses to date are failing to solve for the information that citizens need to make informed decisions about important issues and debates. The Future of News series brings together leading practitioners, scholars, and thinkers to imagine new business models, policy responses, and journalistic content that can support a dynamic future for news in Canada.

I recently had the privilege of appearing before the House of Commons Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage, as a witness in hearings on a National Forum on the Media. I was, of course, honoured to be invited to participate. My opening remarks are included below and you can stream the entire session here.

I’m sorry to report that I found the experience disillusioning—despite having pretty low expectations going in. (I had read Jen Gerson’s essay about her experience testifying before the House of Commons Standing Committee on Bill C-18. “I admit that it’s one thing to be cynical in theory, and another entirely to find one’s cynicism proved valid,” she wrote in 2022. “It was absolutely astonishing to me the degree to which the meeting was nothing more than political theatre …”)

Given that I took the opportunity to argue against further government subsidies to the media, I probably should not have been surprised by the response from some MPs.

One standout moment occurred when Liberal MP Taleeb Noormohamed characterized my testimony as calling for “no government support for journalism and news,” despite the fact that I’d already said I supported a robust CBC, a point that a fellow witness immediately pointed out. (In what universe is an annual $1.3 billion for the CBC—several days later, $1.4 billion—an end to all government support?) That same MP went on to argue that since Postmedia and others had taken advantage of subsidies, and had remained critical of the government, clearly there was no issue. What the member failed to grasp was that it doesn’t matter whether politicians think that the subsidies don’t interfere with the independence of the press. What matters is that the public thinks they do.

I also had the surreal experience of hearing Brent Jolly, head of the Canadian Association of Journalists, warn that without media subsidies, our country would “devolve into a nation of TikTokers and YouTubers, who are there, not communicating stories in the public interest, but are just looking to profit off of, you know, whatever rumour is going around the Internet”—thereby denigrating journalists at the independent media outlets that have declined subsidies.

But by far the most troubling comment came from Sarah Andrews, director of government and media relations for the Friends of Canadian Media lobby group. The remarkable exchange began with a prompt from MP Martin Champoux, on a point I had raised earlier about the need for listening to the public and hearing what it wants from its media. Champoux paraphrased a famed quote from Henry Ford: “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.” When asked to respond, Sarah Andrews said that when it comes to feedback from the public, we should “take that with a grain of salt.”

She later added: “What concerns me, with talking with a lot of Canadians about their opinions, is that people don’t necessarily understand what journalism is. So, public opinion should be taken with a grain of salt.”

Imagine participating in a House of Commons committee meeting, held in the seat of our democracy, and blithely dismissing the importance of listening to its citizens. It’s a profoundly antidemocratic impulse, as I pointed out.

Anyone still scratching their heads about the decline of public trust in the media should take note. As one commenter, watching via livestream, put it on Twitter: “If you guys can’t figure out what’s wrong … it’s that.”

Opening remarks, Commons Heritage Committee, February 27, 2024

Good afternoon to the committee and thank you for inviting me to participate in your study on a National Forum on the Media.

My name is Tara Henley, and I’m a journalist and author in Toronto. I am the host of the Lean Out podcast, a subscriber-supported, weekly current affairs show that interviews guests from around the world, including many journalists. I myself have been a journalist for 22 years, with experience in newspapers, magazines, digital, radio, and television, as well as publishing a current affairs book.

For the past year, one of my central lines of inquiry at Lean Out has been the collapse of the media. In trying to unpack what’s gone wrong, I’ve interviewed researchers, authors, historians, and professors. I’ve covered reports, journalism panels, and forums. I’ve also read a large volume of emails and comments from the public—and have spoken with journalists in both legacy and independent media, as well as opinion writers across the political spectrum, and media entrepreneurs.

I am currently writing the 2024 Massey Essay on the state of the media, which will be published in the Literary Review of Canada this spring. The focus of that essay is on declining trust in the media.

As this committee has already heard, the problems facing Canadian media are complex and multifaceted, and our newsrooms are under enormous pressure.

We know that the collapse of the Canadian media is largely economic. The internet has disrupted our industry, and the advertising business model has imploded. We also have heard from witnesses at this committee that the industry faces challenges with ownership and consolidation.

We have seen mass outlet closures, dwindling audiences, and mass layoffs, and, by some estimates, there are now just 10,000 to 12,000 journalists in this country. Government intervention in the industry has also presented challenges for some players, including independent and digital outlets, as it has resulted in Meta pulling out of news in Canada. We heard powerful testimony on that from media CEO Brandon Gonez.

The media is in a profoundly weakened state, and there are consequences to this. Good journalism involves revealing inconvenient facts, airing unpopular perspectives, and challenging dominant narratives. The volatility of our industry risks breeding conformity and caution, in leadership and in our press corps, which can erode the quality of coverage.

In the current climate, the training for the next generation is also jeopardized, as there are fewer mentors. And fewer outlets—particularly fewer local news outlets—for young journalists to train at. The economic precarity of journalism means, as well, that young people without family financial support are less likely to go into the business and to be able to live in the expensive cities where most of our media are now concentrated and do internships or poorly paid jobs. This reduces the diversity of perspectives in our newsrooms at a time when we most need to increase it.

As our industry is collapsing, the public relations industry is exploding. Cecil Rosner, formerly of The Fifth Estate at CBC, notes in his recent book that journalists are now outnumbered by PR professionals by a ratio of 13:1, with entire teams now standing between reporters and those they report on.

We in the media are not just facing catastrophic economic and structural pressures. We’re also grappling with a serious decline in public trust. And a citizenry that is increasingly tuning out from the news and is increasingly hostile towards journalists.

These are all major problems for maintaining a robust and healthy press. So, I very much support the idea of a National Forum on the Media. Especially one that would have meaningful participation from the public. If we want to save the Canadian media, we are going to have to forge a journalism centred on the public interest, as the public understands it, as witnesses Sue Gardner, Jen Gerson, and Colette Brin have already persuasively argued before this committee.

I do not believe that the government should have a role in facilitating a news forum, and I especially don’t think it should fund it. In my view, any funding that flows from the government to the media at this point would hinder our attempts to rebuild trust.

In my research, there was evidence to suggest that subsidies have created an environment in which segments of the public believe the media has been bought off by government. We heard this view at committee, from Unifor’s Lana Payne, who said her members face complaints that they are a “tax-funded mouthpiece for the PMO.” We know from a 2023 Angus Reid poll that most Canadians—59 percent—oppose government funding of private newsrooms, believing it compromises journalist independence.

I want to be clear: I do not believe subsidies result in direct editorial interference.

But that doesn’t mean they don’t impact public trust. As an industry, we have a duty to insulate ourselves from the power we are meant to hold to account. The media derives its credibility from its independence from power, particularly government power. Maintaining public confidence in that independence is of paramount importance. As important as maintaining the independence itself.

As such, we must contend with the public perception of government funding, and understand it likely erodes trust—unfortunately at the exact moment that the Canadian press most needs to rebuild trust.

Without trust, we have no audience. Without an audience, we have no revenue. Without revenue, we have no path forward for the Canadian media. And without the media, we do not have an informed electorate and a functioning democracy.

The Canadian media needs to be saved, that is true. My message is simple: The government cannot save us. We have to save ourselves.

This column originally appeared on tarahenley.substack.com. The Future of News series is supported by The Hub’s foundation donors and Meta.

Recommended for You

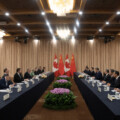

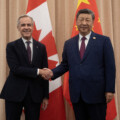

‘Canadians don’t trust China’: Hub Politics on the risks and rewards of Carney’s China trip

So David Eby does want a pipeline, after all?

‘Bending the knee’: Former Canadian ambassador on Prime Minister Carney’s misguided trip to China

Disabled Canadians deserve more support from a stingy federal government