This excerpt was originally published at BMO.

We have been going on, and on, for nearly a year about the growing divergence between the North American economies—a surprising/amazingly resilient U.S. set against a struggling Canada. Just as there were some indications the gap may be narrowing in early 2024, the March employment reports put an exclamation point on the wedge. Last month saw the U.S. churn out yet another chart-topping payroll gain of 303,000, clipping the unemployment rate to 3.8 percent.

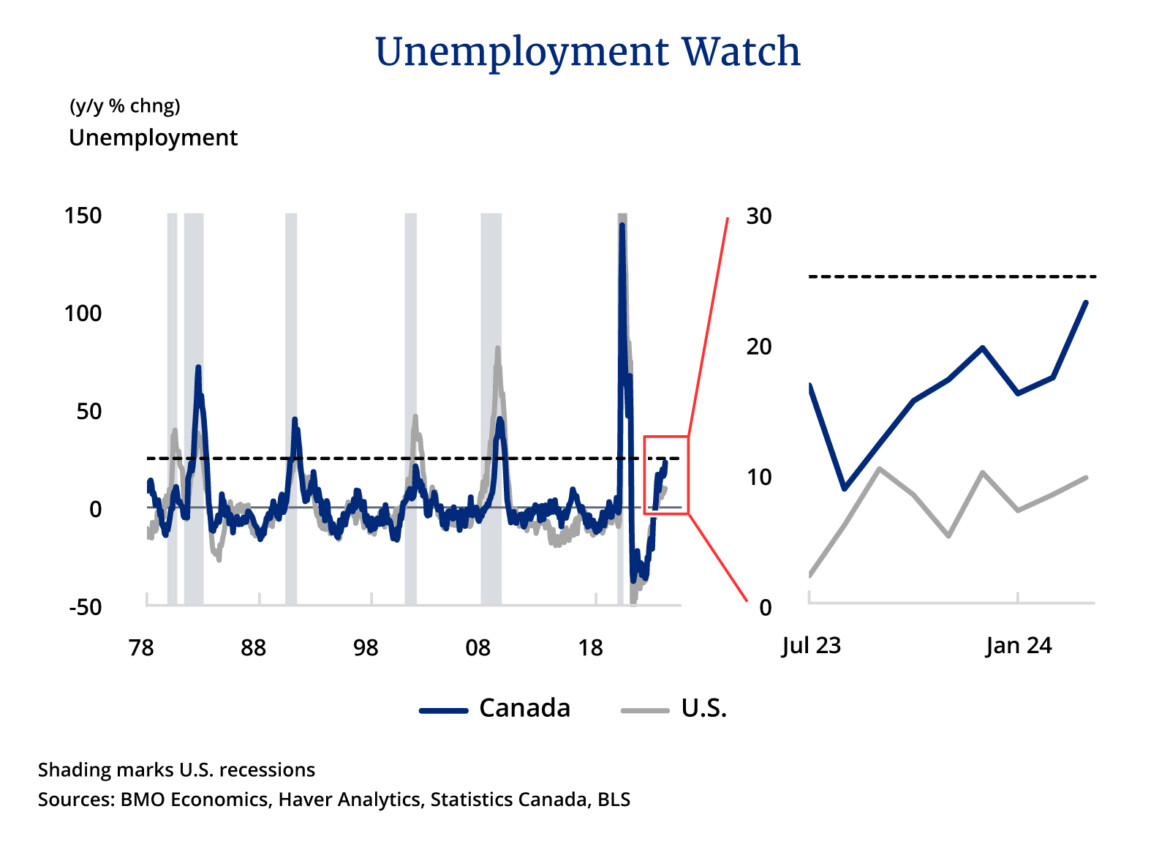

In the meantime, Canada saw a full eclipse of the jobs, with a 2,200 drop, sending the unemployment rate up 3 ticks to 6.1 percent. That 2.3 percentage point divide between the jobless rates is at the very upper end of the range over the past twenty years, aside from the madness of the pandemic. This simply reinforces our conviction that the Bank of Canada will be leading the Fed on the rate-cut front, just as it led on the way up the hill two years ago.

Markets have been steadily reeling back expectations of Fed rate cuts almost since the year began, and recent events pulled the string a bit further. While Chair Powell sent soothing tones in a speech last week, suggesting the bigger picture had not changed, the freshly converted uber-hawk Kashkari opined that perhaps no rate cuts were needed at all this year. With job growth still chugging along, GDP on track for at least a 2 percent advance in Q1, the factory PMI pushing back above 50, and now oil prices at $87 threatening to lift headline inflation again, it’s not obvious that he’s out of line. We remain entirely comfortable with our call that the Fed will wait until July to start the rate cuts. After bravely staring down fading prospects of rate relief through Q1, equities showed a flicker of concern this week, with the S&P 500 dropping roughly 1 percent from the recent record high.

It is a very different post-jobs conversation in Canada. Full disclosure, there has been some wavering on our call for a June cut by the Bank of Canada, especially in light of a run of surprisingly sturdy GDP growth to start 2024, as well as solid financial markets, a stabilizing housing market, and fading Fed rate cut prospects. Standing against that, the two main pillars of support for our relatively dovish call on the BoC were low inflation and rising unemployment. The past two CPI reports have been stunningly helpful, with ex-shelter inflation dropping to a mere 1.3 percent y/y. But the snapback in oil and sticky wage growth of around 5 percent could frustrate further progress, and threaten to keep inflation expectations firm.

Against that backdrop, the steep rise in the unemployment rate last month is an important development, as it suggests that wage trends will eventually ebb. In fact, with the jobless rate pushing above 6 percent, one can make the case that the labour market is no longer tight in Canada. One rule of thumb we watch is the year-over-year change in the number of unemployed people. Over the past 40 years, in both Canada and the U.S., any time it has risen by 25 percent or more, the economy has been in recession (Chart 1). (Note that Canada didn’t quite get there in the 2000/01 cycle, and that period was not judged to be a recession by the semi-official arbiters of such.) The back-up in March left the number of unemployed Canadians up 23 percent year-over-year, right at the edge. In stark contrast, the same metric shows a rise of less than 10 percent for the U.S. economy, reinforcing North America’s wide divergence. A rather obvious rejoinder is that the surge in Canada is driven by smoking population trends, and can’t be readily compared with the past.

We won’t need to wait long to find out exactly how the Bank of Canada views these conflicting trends, with the rate decision and MPR on Wednesday. While there’s not much debate that the Bank will hold rates steady again at 5 percent, there’s a lot of debate over just how dovish they will sound. Even with a moderate upgrade in the 2024 growth outlook (the BoC was previously at 0.8 percent, we’re now at 1.2 percent), inflation is nicely tracking below their estimate of 3.2 percent for Q1 (likely 2.9 percent), so we look for the Bank to open the door a crack for coming rate cuts.

Just prior to the BoC announcement, the U.S. CPI is likely to flag a small warning on the impact of higher oil prices, with headline inflation rising a couple ticks to 3.4 percent, even as core is expected to dip to 3.7 percent (both on monthly increases of 0.3 percent). That energy-led uptick could be mirrored in Canada’s CPI the following week, albeit holding below 3 percent. For both the job market and inflation, Canada is showing some separation from the U.S., and we suspect that will drive a small separation between BoC and Fed rate policy in coming months.

This excerpt was originally published at BMO.

Recommended for You

Trevor Tombe: How is Carney going to pay for his commitments? There are some tough choices ahead

Chris Spoke and Peter Copeland: Ontario is missing millions of homes. Here’s where the government is failling—and how it can actually make a meaningful difference

‘The cost of permitting has ballooned’: Sharon Singh on Canada’s broken regulatory system

Sean Speer: Pierre Poilievre is right to favour pro-worker policies over increasing immigration