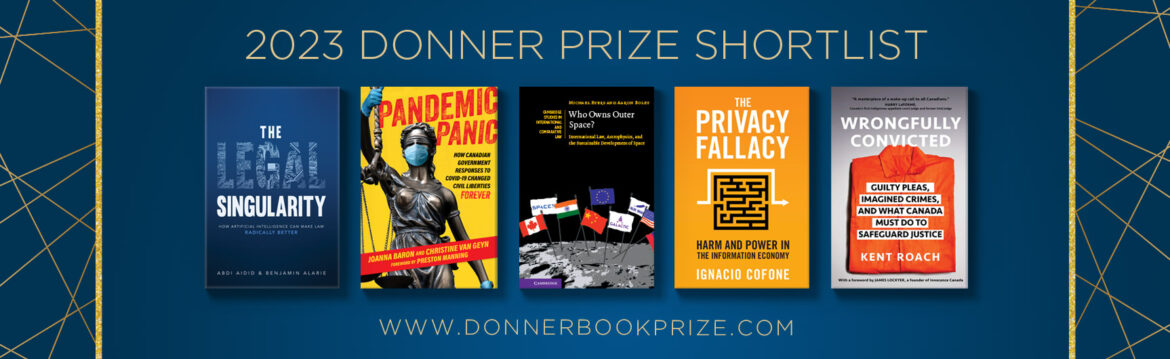

As part of a paid partnership, this month The Hub will feature excerpts from this year’s five shortlisted books for the Donner Prize, awarded to the best public policy book in Canada. Our podcast Hub Dialogues will also feature interviews with the authors. The winning title will be awarded $60,000 by The Donner Canadian Foundation on May 8th.

The following is an excerpt from Wrongfully Convicted: Guilty Pleas, Imagined Crimes and What Canada Must Do To Safeguard Justice (Simon and Schuster, 2023).

Since my first year of teaching criminal law in 1989, I have used a case study of how Donald Marshall Jr. was wrongly convicted of murder in 1971. The case study replaced my colleague Marty Friedland’s previous case study of Steven Truscott, who was sentenced to death in 1959 when he was fourteen years old. Truscott was finally acquitted with help from Friedland’s daughter in 2007 of the still-unsolved murder of a classmate. Both Marty and I wanted our students to study un-true crime as well as true crime. They need to know that the “facts” presented in the appeal court judgments they read are contested. Sometimes these facts are not true.

Both the Marshall and the Truscott cases were who-done-it? murders that convicted the wrong person. Many people continue to associate wrongful convictions exclusively with the mystery of “wrong-person wrongful convictions.” These convictions are a staple of true crime novels and movies. But wrongful convictions are not entertainment. They are about human mistakes and human suffering. These types of wrongful convictions still occur, but we now know about other, even more insidious types of wrongful convictions.

False guilty pleas

The vast majority of Canada’s remedied fifteen guilty plea wrongful convictions have involved women, Indigenous or other racialized people, and those with cognitive difficulties. Their stories need to be understood to ensure that we do not blame victims for making understandable choices. Canadians need to understand the hard truth that sometimes a false guilty plea to accept a deal to a reduced sentence is a completely rational decision.

Imagined crimes

In some cases, people plead guilty or are convicted after a trial even though there was no crime. In other words, they are convicted of un-true crimes that are imagined by police, prosecutors, expert witnesses, judges, and juries. Such imagined crimes constitute twenty-eight of the eighty-three wrongful convictions presently in the Canadian Registry of Wrongful Convictions. In seven of these cases, the victims of the justice system’s unfounded suspicions were Indigenous. They include two Indigenous men and one Indigenous woman who were wrongfully convicted of murdering young children in their care when the children died from undetermined causes or by accident. The racist stereotype of Indigenous people as bad parents prone to violence is unfortunately as old and pernicious as the residential schools.

The stories contained in the Canadian registry of wrongful convictions have made me more disillusioned about the Canadian criminal justice system than I was as a younger law professor. I am not, however, completely disillusioned. Not yet. Canada can do better to prevent wrongful convictions, though we will never eliminate them. The Supreme Court recognized that in 2001 when it wisely took the death penalty off the table. We know that wrongful convictions are inevitable. This makes it imperative to find quicker and better ways to correct them and to attempt as best we can to make amends for the incalculable damage they cause.

During the summer of 2021, I was privileged to assist Justice Harry LaForme and Justice Juanita Westmoreland-Traore as they conducted public consultations about how best to improve Canada’s approach to discovering and correcting wrongful convictions Under the existing system, applicants who have exhausted their normal appeals must apply to the federal minister of justice for what is described in the Criminal Code as the “extraordinary remedy” of a new trial or a new appeal. They must effectively identify new evidence to justify their applications, though most of them will lack the funds and the necessary powers to find the new evidence. Crucial evidence may, moreover, be buried in police and prosecutors’ files or even destroyed.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Zoom allowed us to hold forty-five roundtables that involved 215 people including 17 exonerees. The exonerees told us they did not care for the federal government’s proposed name for a new review body, the Criminal Cases Review Commission, even though this same title is used for similar bodies in England, Scotland, Norway, and New Zealand. They pointed out they were people, not criminal cases. They wanted their convictions reinvestigated and retried. They did not want their cases to be the subject of desktop reviews by bureaucrats in Ottawa. They also told us about the inadequate support they received. Many of them obtained no compensation for the injustice they lived. Those who did obtain compensation often had to wait years. They generally had to threaten to sue or actually sue in court the governments that had wrongfully convicted them.

Whereas previous Canadian commissions of inquiry greatly admired the English Criminal Cases Review Commission, which has been operating since 1997, we heard it has suffered from massive budget cuts that have increased caseloads and required most applications to get nothing but cursory reviews.

We were impressed by the New Zealand commission, created in 2019. We spoke to its chief commissioner as well as with two Maori commissioners. They genuinely wanted to treat applicants, including those from the over 50 percent Maori prison population (compared to 17 percent of the population), with more respect and dignity than these people received from the rest of the criminal justice system. At the same time, we also heard alarming concerns that the New Zealand commission was already overloaded with applications.

The uncertainty surrounding the full implementation of the report is one reason why I agreed to write this book. New legislation to establish a new commission has the potential to be the most important law reform with respect to wrongful convictions in a generation. At the same time, if the new commission is underfunded and does not have sufficient powers, the situation could possibly become worse for the wrongfully convicted. At the very least, the hopes that David Milgaard and other exonerees had for the commission would not be realized. The stakes could not be higher.

Another reason I am writing this book is that the wrongful convictions that have been unearthed and described in the Canadian Registry of Wrongful Convictions should be better known. Even recently corrected wrongful convictions are not well publicized or known. Without the clear-cut stories provided by DNA exonerations and a thriving investigative media, wrongful conviction amnesia may be setting in.

Recommended for You

Michael Kaumeyer: Polite decline: Canada’s aversion to being our best is holding us back

Howard Anglin: Lament for a Lament

‘A place where anybody, from anywhere, can do anything’: The Hub celebrates Canada Day

Peter Menzies: It’s no wonder Canadians are tuning out the legacy media