As you were filling out your tax return last month, did you notice something odd? Most of the services that you would want those dollars to go towards are delivered by the provincial government, so why did you send most of your taxes to Ottawa?

Tensions are high between governments in the federation right now. They are strained in large part by fights over how much federal funding is coming to fill gaps in areas of provincial jurisdiction like crime, education, homelessness and addictions, seniors’ care, and health and social services more broadly. Sometimes what gets backs up even more than a lack of dollars are the strings attached to new federal funding dictating how and where to fill these gaps.

Those decisions do not only come from federal politicians—federal forays into provincial areas mean a whole second bureaucracy needs to be fed before that tax dollar gets back to your hospital or seniors’ home. In addition to the tax dollars siphoned off for that double administration, taxpayers in Ontario, Alberta, and B.C. are responsible for effectively shipping their tax dollars ($4,000-5,000 per Albertan annually) via Ottawa to other provinces mostly for provincial services.

With new federal programs like pharmacare, dental care, and housing initiatives being controversially added to the recent federal childcare agreements, these problems are only going to get bigger. One step towards strengthening unity in Canada and making politicians more accountable for their responsibilities is to even out the tax share taken by your federal and provincial governments.

While this tension can be slackened when federal programs respect provincial autonomy and add purse strings that are barely visible, so long as the strings are held by elected and unelected decision-makers in Ottawa, the next fight about expanding government will always be just around the corner.

The imbalance: tax power vs. responsibility

Why do provinces go cap in hand to Ottawa to fund services for which they are constitutionally mandated to provide anyway? And when they come back empty-handed, why do they shrug and point a finger back toward the Gatineau hills?

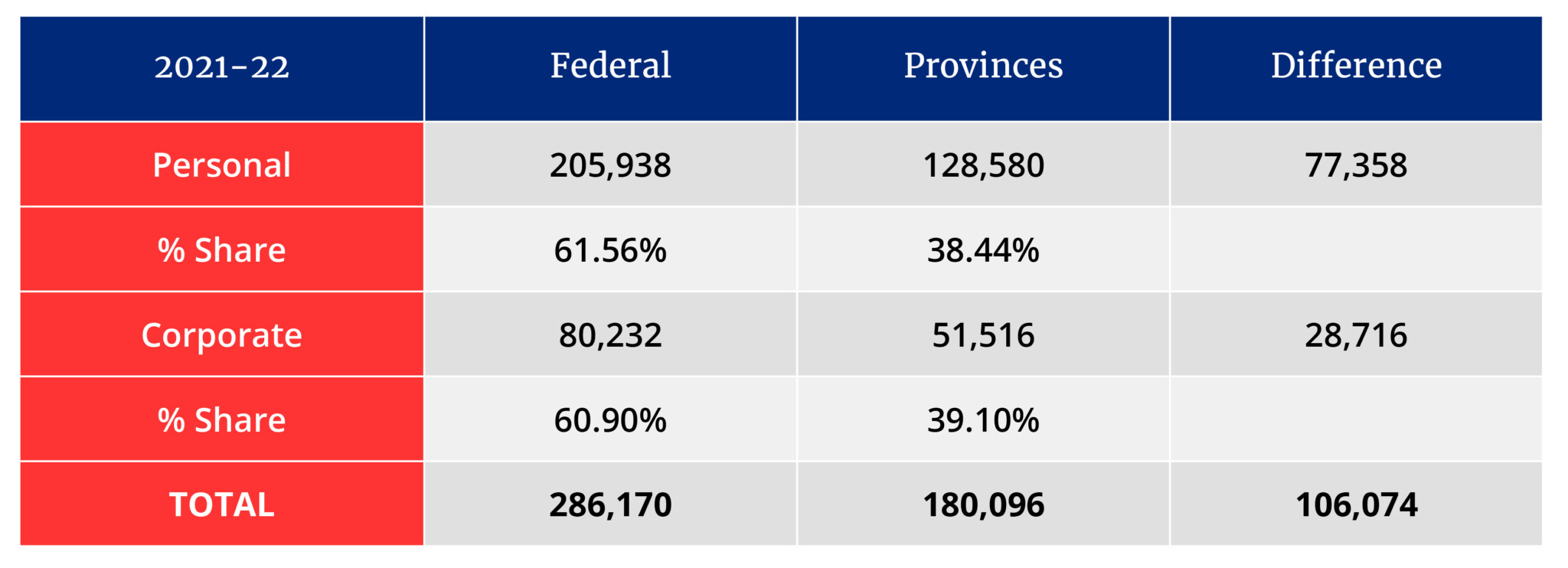

It is because of that odd thing we did last month: sending almost twice as much of our income to Ottawa as we did to our provincial capital. According to Finances of the Nation in 2021-22, we sent them $77 billion more in personal taxes, and the federal corporate tax bill was $28 billion higher than the provinces combined. In recent years the gap has averaged $90-100 billion.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

For better accountability, the government responsible for delivering a service should be the one taxing us for it. If the people of a province want more spending on a given service, they can elect a government that will prioritize that—with some combination of shifting dollars or raising taxes and/or debt to do it.

Citizens lobbying Ottawa to improve their provincial services makes even less sense than provinces doing it, except for the distortions caused by this fiscal imbalance.

The reasons our original constitutional documents put social programs under provincial purview were good enough that, despite the significant growth of the welfare state, they stayed there in 1982.

Different regions have always had different pressures and needs, and different ways of meeting them. What they have not had is the fiscal independence to pay for them without their taxpayers’ dollars going through Ottawa.

This imbalance is not new, and in many cases, the provinces gradually brought it upon themselves by signing on to various federal funding agreements. What used to be more prominent, however, was a consensus that there needed to be latitude for provinces in how they used these funds (on constitutional as well as practical grounds). The Meech Lake and Charlottetown proposals, for example, both featured provisions for provinces to opt out of new national programs and instead get their share as a block fund.

Seguin report

Federal funds today virtually all have federal strings and sit on the edge of the chopping block when sporadic rounds of belt-tightening take place. The suggestion made here to even out the tax powers gets past that, which is why it has had support in the past.

In 2002 the Fiscal Imbalance Commission struck by the Quebec government proposed to rebalance tax power by moving federal tax points as well as GST revenues to the provinces to replace the unpredictable Canada Health and Social Transfer (CHT). In addition to securing predictable self-generated funds, another aim was to increase autonomy in program delivery.

“The situation can be summed up pretty easily,” said the president of the commission Yves Seguin: “The federal government occupies too much tax power compared to its responsibilities.”

The resulting “Seguin Report” made numerous recommendations, but emphasized the need for a major tax room shift. It argued (correctly in my opinion) that only increased tax power can truly reduce the provinces’ dependence on federal decisions for how and where to spend on the services they deliver.

Given provincial services are more than half of government spending, one could certainly argue the provincial share should actually be higher, but our compromise 50/50 proposal here means we need to close a $100 billion gap as outlined above.

To get a sense of what would be required on the revenue side, ceding GST to the provinces ($52 billion in 2022) could close that gap, as could switching 25 percent of our federal personal taxes to the provinces. On the spending side, drastically reducing the CHT ($52 billion) and eliminating the Canada Social Transfer ($17 billion) would do the trick. Given Ottawa likely wants to preserve a sizeable CHT baton with which to enforce the Canada Health Act, it would likely prefer to take a hard look at different places to back out of provincial areas—great!

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau arrives to meet with Canada’s premiers in Ottawa on Tuesday, Feb. 7, 2023 in Ottawa. Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press.

Barriers to reform

So if there are clear reasons to shift the tax power significantly and straightforward ways to do it, why has it not happened?

One reason is that as these programs emerged last century provinces usually signed on to federal agreements; sometimes, this was because of advantages of scale, but it was also politically convenient to avoid being the ones raising their tax rate to pay for them. Repeatedly relying on the feds’ larger tax room only exacerbated the imbalance.

The tax power shift proposed here would mean provinces raise their rates to make up for the federal cuts in tax (and spending) but would be more palatable politically because it would be a sudden switch between orders of government and not necessarily a tax hike at all.

Another barrier to reform is the reluctance of the federal government to give away power, and the difficulty the provinces have in changing federal programs without Ottawa’s cooperation. The federal influence over these programs does help standardize services nationwide. This is for the better or the worse depending on your perspective or the program—but the feds of course would insist it is for the better.

Besides standardization, one of the benefits they and other supporters of the fiscal imbalance tout is that using federal funds helps promote equity between provinces. Or, in economist-speak, the vertical imbalance offsets the horizontal imbalance. Taxpayers from wealthier regions pay more in federal taxes, but payments come back roughly per capita so billions of dollars from wealthier provinces quietly go to support services in those with less economic activity.

Giving tax points back to provinces boosts coffers in B.C., Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Ontario but leaves the other 30 percent of the country a little short without the subsidies inherent in per capita payments.

This is the biggest political barrier to rebalancing tax powers. It would likely necessitate something like a five-year top-up for the lagging provinces to smooth out the adjustment, but for some, autonomy would eventually come at a price.

This effect was acknowledged in the 2002 Seguin report, but Seguin pointed out that the equalization program is the one that is designed to equalize with direct payments. If there are remaining equity needs, they should be openly and fairly addressed there, not quietly implicit in countless federal forays into provincial services.

At Fairness Alberta, we have pointed out that there is a distorting and inefficient amount of redistribution happening with equalization proper, made worse by all these quiet forms of redistribution on top of it. To point out one striking fact: despite provinces becoming more equal over the last decade, roughly $9 billion of Ontarians’ taxes are sent by Ottawa to fund provincial services in their neighbouring provinces through equalization alone. Even if the tax powers were balanced as proposed here, the feds would still be facilitating massive levels of redistribution.

Reducing these quiet forms of redistribution may be more of a feature than a bug.

Conclusion

To be sure, there are many permutations and combinations that can get us to this balance, and almost all of them will be controversial. But if you agree that the “let’s count on Ottawa to ensure our provincial services are strong” status quo is not working, then it is time to restart this conversation that has been alive for most of Canada’s history but lately dormant.

If we even out the “tax room” between federal and provincial governments their powers will better reflect the responsibilities each has been assigned.

In addition to aligning better with the Constitution, this will mean less finger-pointing, less regional alienation, and more political accountability for the services we want delivered.

Recommended for You

Ginny Roth: J.D. Vance, Pierre Poilievre, and how they slice their economic pie

David Polansky: As President Biden leaves the race, will the Democratic Party hodgepodge hold?

Five Tweets on Western Canada’s devastating wildfires

RCMP spending to protect MPs may have risen 112% since 2018, as Canadian politicians face greater rise in threats