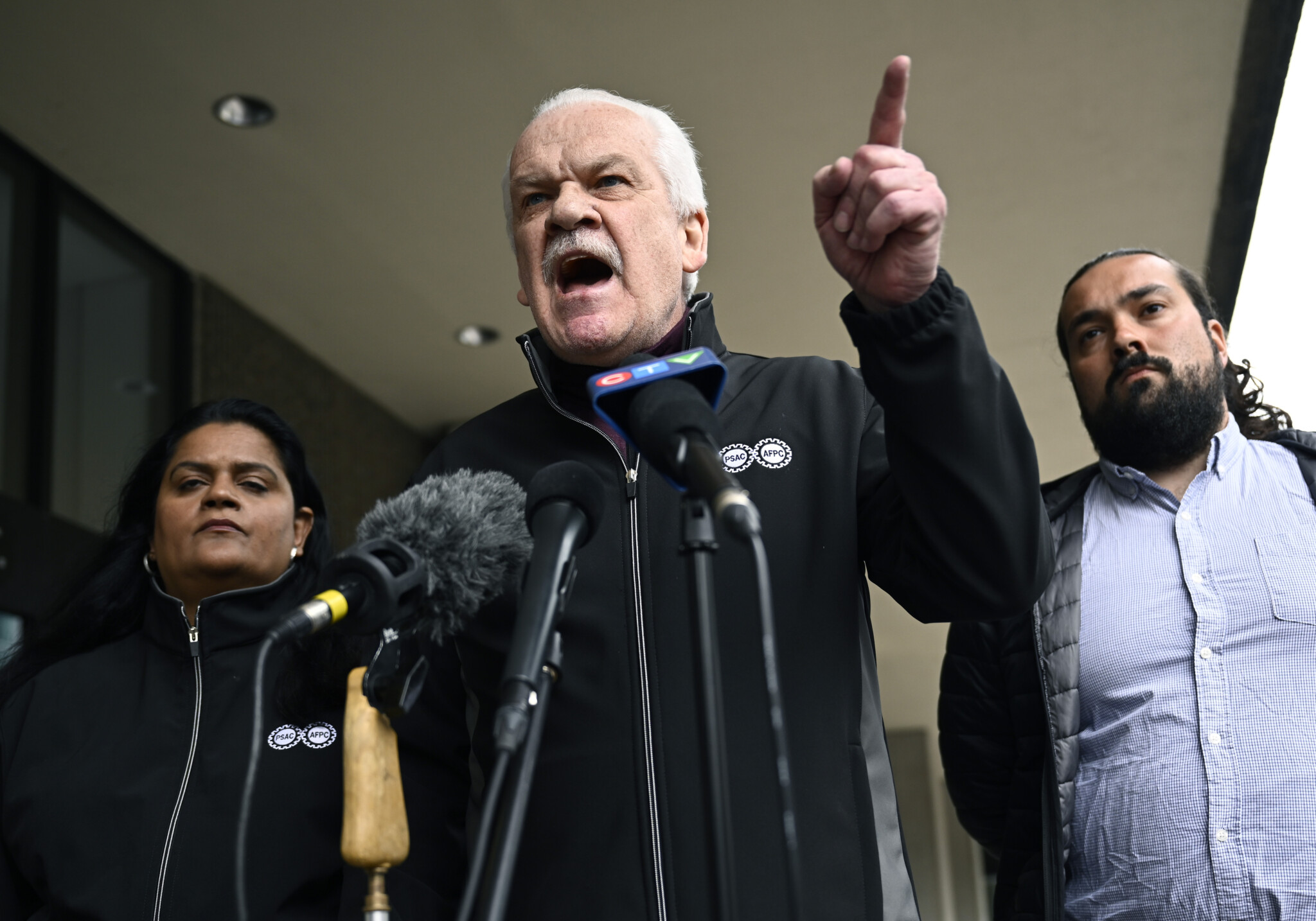

Summers in Ottawa are usually pretty steamy, but the summer of 2024 promises to be positively hellish and discontented as public sector unions rattle their sabres in response to the federal government’s directive that starting this fall, federal civil servants will be expected to work in the office three days a week instead of two.

This tough talk set off many of the world’s smallest violins, with commentators pointing out that many private sector workers are already spending more time back in the office (or have never been able to work remotely in the first place) and that public sector workers—who already enjoy unheard-of-in-the-private-sector job security and pensions—were largely shielded from the economic pain suffered by most Canadians during the pandemic.

Add to this a sense that public servants haven’t been delivering (such as widespread frustration due to delays in getting a passport) and unflattering case studies of bureaucrats behaving badly (I’m looking at you, 232 Canada Revenue Agency employees fired for improperly claiming CERB or the ArriveCan app scandal) and it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that complaining about one more day back in the office is peak entitlement and tone deafness on the part of the unions.

Politically, the Trudeau government is getting hammered in the polls and facing a broader public that does not have a lot of sympathy for an aggressive public sector. And—let’s be brutally honest—if we layer on longstanding stereotypes about “lazy bureaucrats” it may very well be the case that a lot of Canadians just want to see them back in the office out of spite.

Is there any agreeable way out of this? There might be—if we think of the looming fight as a very rare opportunity to give both public servants and Canadians at large something they really want.

Start first with public servants, most of whom just really, really want as much remote work as possible. Unlike most people in the private sector, they have very powerful unions to go to bat for them and it’s probably the case that the aggressiveness being displayed by union leaders simply reflects what they are hearing from their members. That’s a signal of how high up remote work ranks on their list of priorities.

Similarly, we should agree that remote work is possible for the lion’s share of public service jobs. There will be exceptions, but a white-collar workforce that works mostly over screens and keyboards is, in most ways, the ideal type for remote work.

And what do Canadians want? They want to be confident that their tax dollars are being used efficiently in the form of civil servants doing work and doing it well. This is especially important because if the stereotype about “lazy bureaucrats” is true, then it doesn’t really matter whether they’re not working at home or not working at a desk downtown. But for honest public servants (I would humbly suggest, the vast majority) who take pride in their work, I suspect most would leap at the chance to prove the naysayers wrong.

The solution? The Trudeau government (or a future government) should work towards negotiating a central trade-off: more remote work for public servants in exchange for public servants accepting more stringent performance and productivity conditions. Public servants get their remote work; Canadians get better accountability.

These are not the only issues on the table of course. The issue of bloat in the public sector is real, with the headcount having ballooned by over 40 percent since the Liberals came into office. This number will almost certainly have to drop, meaning that even if remote work becomes the norm, it won’t be enjoyed by everyone who is a federal employee today.

Similarly, phasing out gold-plated defined-benefit public employee pensions, which currently have an unfunded liability of over $100 billion should be on the negotiating table. Grandfathering these plans for current employees while getting the unions to agree to move new employees onto a more sustainable defined-contribution plan should be the goal for any government looking to alleviate future risk to taxpayers (it’s possible: private sector unions have made similar concessions in recent years).

We could even consider a truly radical shift: moving the federal public services to a remote-first model. This would open up all kinds of interesting possibilities. Over time, public sector jobs could be more evenly spread around Canada rather than concentrated primarily in the Ottawa region, bringing economic benefits to other parts of our vast country. It would also help make the civil service more reflective of Canadian society, by ensuring a workforce with more proportionate regional representation.

Under this model, teams from various ministries and departments could gather in Ottawa, perhaps once or twice a year, for weeklong in-person meetings and team building. Most federal buildings could still be sold off, with the remainder repurposed for a “rotating team” structure. Beleaguered downtown Ottawa restaurants and bars could probably benefit from the constant influx of out-of-towners cycling through.

Of course, both the government and the unions have to decide what they value most and try to get the best deal, for Canadians and for their members. But if the reaction from the unions over one more day a week in the office is any indication, offering remote work may be the bargaining chip governments need to make broader, lasting reforms.

Labour strife, especially in the public sector, is always lemon. But given the unique dynamics at play today, with a little savvy bargaining, maybe the government and unions can make a little lemonade.

Recommended for You

The Notebook by Theo Argitis: Trump halts trade talks, Carney’s trade-offs and John McCallum’s legacy

Lydia Perovic: The future of history looks bleak, if Toronto’s museums are any indication

The Weekly Wrap: The Liberals must abandon their internet regulation agenda

‘A direct attack’: The Roundtable on Trump’s surprise trade announcement and Canada’s immigration debacle