A recent poll found a stark divide between federal public servants and the rest of the Canadian public on the question of whether the former ought to be back in the office. Less than one-quarter of public servants said they support the Trudeau government’s decision that they must be in the office at least three days per week compared to nearly two-thirds of non-public servants.

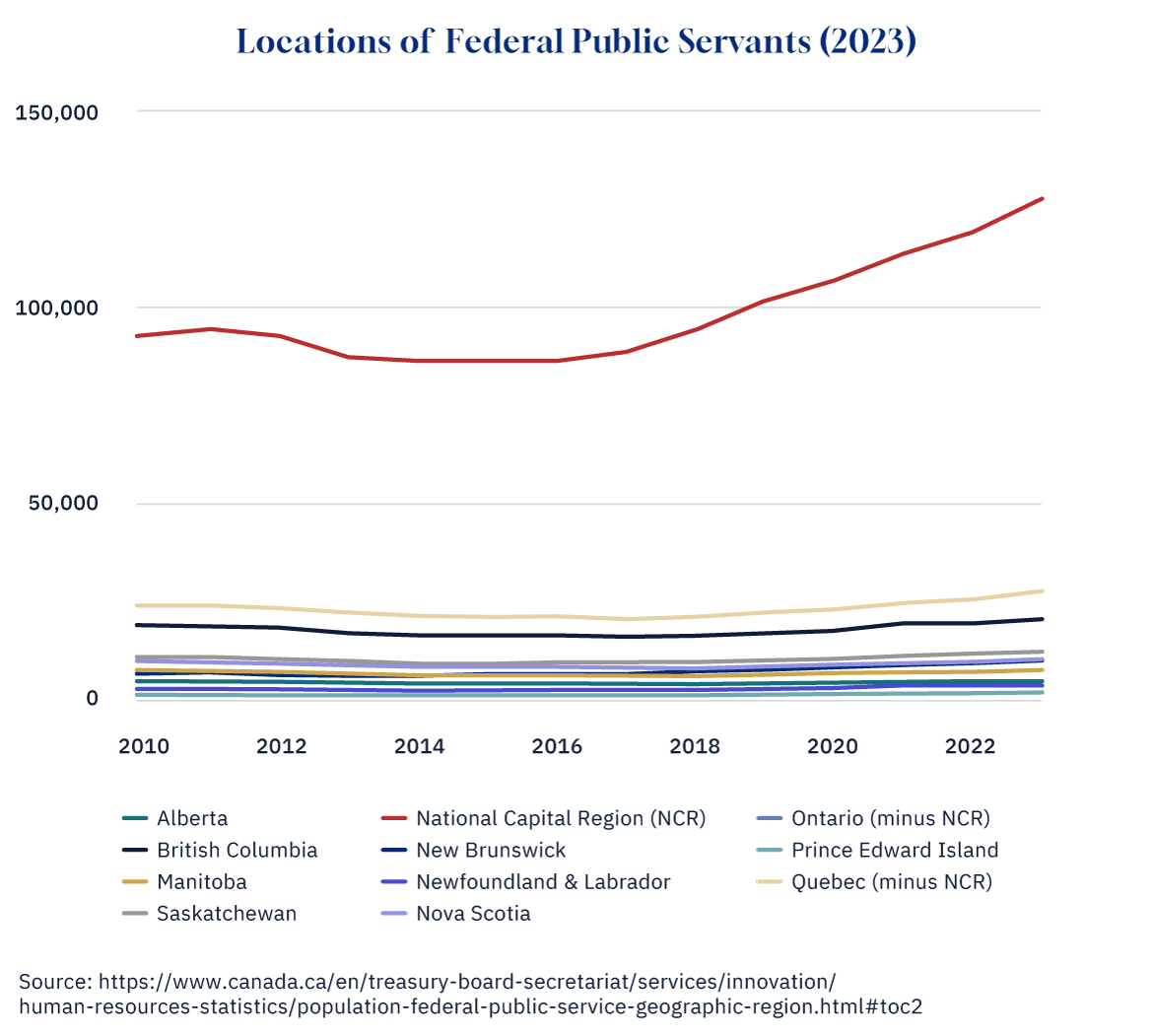

It may reflect a broader divide between the federal government and the rest of the country reflected in the growing concentration of federal officials in the National Capital Region. Today more than 47 percent of those who belong to the core public administration are in Ottawa/Gatineau. That’s up by more than 4 percentage points since a decade ago and as many as 10 or 15 points from four decades ago.

There’s something unhealthy about the growing physical disconnect between the federal government and the people and places that it’s ostensibly supposed to serve. Long-time public administration scholar Donald Savoie has even argued that it may explain the decline in the quality of service delivery.

Consider for instance that as technology and the rise of remote work have made a decentralized federal workforce more possible, the data show that it’s counterintuitively becoming more centralized. The number of federal employees (and their share of the overall public service) has grown in spite of these trends (see below).

There are consequences here for policymaking and governance. The National Capital Region isn’t representative of the country. For instance, its rate of bilingualism is roughly double the national average. The share of residents with a bachelor’s degree or higher is more than 10 percentage points higher than the Canadian average. And its median income is the highest in the country. The people who comprise the federal public service, in other words, generally have quite distinct backgrounds and experiences from the public that they’re serving.

The risk of course is that the federal government comes to occupy a small bubble that exists on the fringe of mainstream experience. The public service effectively becomes a foreign service in a strange land.

Perhaps, then, the discussion about public servants returning to work ought to be expanded to consider where precisely they’re working. Decentralizing the federal government outside of the National Capital Region would not only presumably lower real property costs for taxpayers but could help to address the unrepresentative effects of the current centralized model.

The Ford government in Ontario has nodded in this direction. For instance, it announced last year that the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board would move its head offices from downtown Toronto to London. The federal government should embrace a similar agenda.

It reflects a broader body of thinking about so-called “place-based policy” and improving public service outcomes. A 2019 commentary by the Brookings Institution for instance was generally positive about the effects of decentralized government but cautioned that it has to be carefully managed. Certain agencies and functions as well as communities themselves may be better or worse fits for decentralization. It has to be more than simply shuffling jobs around the country. The process must be evidence-based rather than politically driven.

The U.K. government’s “decentralization” exercise in 2004, which aimed to move 20,000 public-sector positions out of Greater London and into economically depressed regions of the country, may incidentally be a model worth examining. Over the following ten years the government moved more than 25,000 jobs and subsequent research found that the relocated jobs had positive effects on local employment and economic activity.

The research suggests that decentralization is most appropriate in instances in which federal policymaking disproportionately affects a particular region or industry. Think for instance of fisheries and oceans or energy or other departments and agencies with a heavy regional focus. They’d be natural target for workforce decentralization.

This of course doesn’t mean that all or even most public service jobs should be moved out of the National Capital Region. There are certain activities and functions that ought to be in close proximity to the cabinet. But there’s no reason to believe that the current geographical distribution of federal public servants is somehow optimal. It’s notable for instance that Canada’s government footprint is more concentrated than our peers in Australia, Britain, France, and the United States.

A well-executed decentralization agenda has in sum various upsides. It can improve the federal government’s representativeness, enable greater cross-cultural interaction, and boost employment and economic activity across the country.

As we debate how frequently federal public servants come into the office, it therefore makes sense that the federal government pursue an agenda to move many of their offices outside of the National Capital Region.

Recommended for You

The Notebook by Theo Argitis: Carney’s One Big Beautiful Tax Cut, and fresh budget lessons from the U.K.

Christopher Snook: Is Canada sleepwalking into dystopia?

Rudyard Griffiths and Sean Speer: The fiscal hangover from the One Big Beautiful Bill hits Canada

‘A fiscal headache for Mark Carney’: The Roundtable on how Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill could affect Canada