DeepDives is a bi-weekly essay series exploring key issues related to the economy. The goal of the series is to provide Hub readers with original analysis of the economic trends and ideas that are shaping this high-stakes moment for Canadian productivity, prosperity, and economic well-being. The series features the writing of leading academics, area experts, and policy practitioners. The DeepDives series is made possible thanks to the ongoing support of Centre for Civic Engagement.

The renowned philosopher and early economist, Adam Smith, made an important distinction between the incidence of taxes on land rents and on stocks: “Land is a subject which cannot be removed; whereas stock easily may…A tax which tended to drive away stock from any particular country would so far tend to dry up every source of revenues both to the sovereign and to the society.” Despite Smith writing these words in 1776, many experts today would agree with his understanding of tax incidence: taxes on immobile land fall on its owners while taxes on mobile capital have wider effects on society.

When the minister of finance, Chrystia Freeland, announced her recent hike to capital gains taxes she claimed in the 2024 federal budget: “We are making Canada’s tax system more fair by asking the wealthiest to pay their fair share.”

The purpose of this DeepDive is to test her claims about who will be affected by the budget’s capital gain tax proposal. The analysis shows that the effect of the capital gains tax affects not just the wealthy but many middle-class and even Canadians with modest incomes.

It will also hurt investment and, as Smith would say, “dry up revenue, both to the sovereign and to society.” In other words, the minister is badly misinformed. Much focus is on capital gains taxes paid by individuals, but the incidence of both the personal and corporate capital gains taxes goes beyond just taxing wealthy capital owners.

The budget capital gains proposal

The budget presented on April 19, 2024, proposes to increase the capital gains inclusion rate from one-half to two-thirds on capital gains, and in the case of individuals, for those gains in excess of $250,000. (Capital gains below this threshold will still be subjected to the one-half inclusion rate.) Corporate and trust capital gains do not qualify for the exemption. The proposal will take effect until June 25, 2024, enabling investors an opportunity to sell assets prior to its enactment at a lower capital gain tax rate, losing the advantage of deferring gains to later years. Final legislation has not yet been released at the time of writing, which may result in some adjustments, creating uncertainty for many investors.

The budget states that 40,000 individual tax filers (0.13 percent of tax filers) and 307,000 corporations (12.7 percent of corporate tax filers) will be affected by the proposal. This has indeed been a major part of the government’s case in favour of tax change. The essential argument is that its design—including the $250,000 capital gains threshold—limits its incidence and in turn its economic costs.

The government predicts $19.4 billion in new revenues over five years, of which almost a third ($6.9 billion) would be raised in the first fiscal year (2024-25) as investors are expected to dispose assets before June 25th. Corporate capital gains taxes will yield the greatest share of new tax revenues: $4.9 billion in the first year (71 percent of the total) and $10.6 billion over five years (53 percent of the total).

The capital gain tax advantage more apparent than real

The strongest argument in favour of increasing the capital gains inclusion rate is linked to past corporate tax reform. Since 2000, the federal-provincial corporate income tax rate has been cut from 43 percent to roughly 26 percent by 2012, reducing taxes on distributed and reinvested profits. Individuals claim a dividend tax credit that avoids double taxation on distributed profits. This credit has declined along with the corporate income tax rate to keep the dividend tax rate aligned with the tax rate on other income. However, the capital gains inclusion rate, which was one-half since 2001 has not changed. As a result, dividends have become more highly taxed compared to the personal tax on capital gain realizations. Given the higher dividend tax rate, companies have an incentive to pay capital gains rather than dividends to investors.

In Ontario, for example, the top federal-provincial capital gain tax rate is one-half of the regular tax rate or 26.76 percent compared to the top personal dividend tax rate of 39.34 percent for eligible dividends and 47.74 percent on ineligible dividends (the higher rate on dividends reflecting the corporate tax rate on small business profits). By moving to a two-thirds inclusion rate, the capital gain tax rate in Ontario rises to 35.69 percent, which is closer but not equal to the top dividend rates.

Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance Chrystia Freeland holds a press conference in the media-lockup prior to tabling the Federal Budget in Ottawa on Tuesday, April 16, 2024. Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press.

While an increase in the personal capital gain tax rate reduces one distortion, it increases others. In the past, it was common to keep the corporate and personal capital gains tax rates aligned so that investors could not avoid capital gains taxes by leaving the asset in the corporation rather than directly owning it. Unlike corporate capital gains, inter-corporate dividends paid from one Canadian corporation to another are exempt to avoid double taxation since such dividends have already been taxed before being distributed. Thus, there is a tax disadvantage for a corporation to earn corporate capital gains taxes compared to dividends, which has been widened by the budget. Companies will try to avoid paying taxes on corporate capital gain realizations by structuring transactions to pay inter-corporate dividends instead.

Further, corporate capital gains will now be more highly taxed than personal capital gains below $250,000. This will encourage investors to hold equity directly rather than through a corporation, introducing a new distortion in the tax system.

This is not the end of the story. Capital gains taxes result in a higher tax on risky assets compared to non-risky investments since the government is more likely to share the gain but not investment losses. Also, the capital gains tax not only applies to gains from reinvested after-tax profits but also inflation—thus, the effective tax rate on real capital gains is higher than on nominal capital gains. Capital gains taxes on realizations encourage investors to hold assets for a longer period even though investors should rebalance their portfolio of investments to earn higher returns (the so-called “lock-in” effect). Overall, the capital gains tax advantage may be more ephemeral than real.

Capital gains and its lifetime incidence

Capital gains are “lumpy” since assets are not disposed on a regular basis. In many cases, a taxpayer may earn more than $250,000 in capital gains in one year but not realize it in other years. Investors could therefore be pushed into the highest income category but only on a temporary basis. On a lifetime basis, some taxpayers may only dispose significant amounts of assets once or twice throughout their lifetime. Examples of major asset disposal events include selling real estate, farmland, business assets or equity, secondary or vacation homes, and deemed realizations at death or departure from Canada.

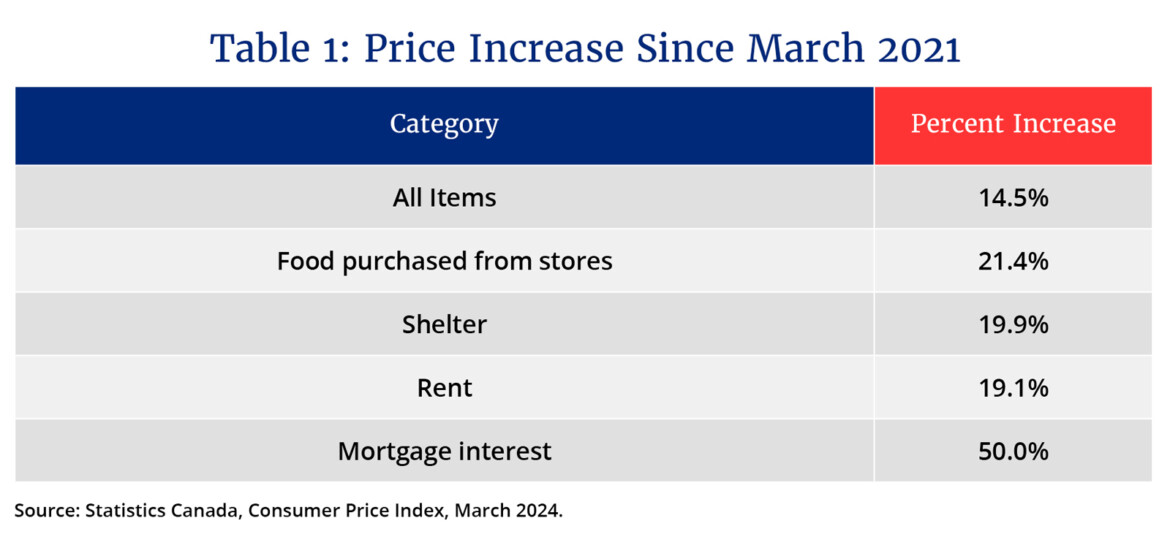

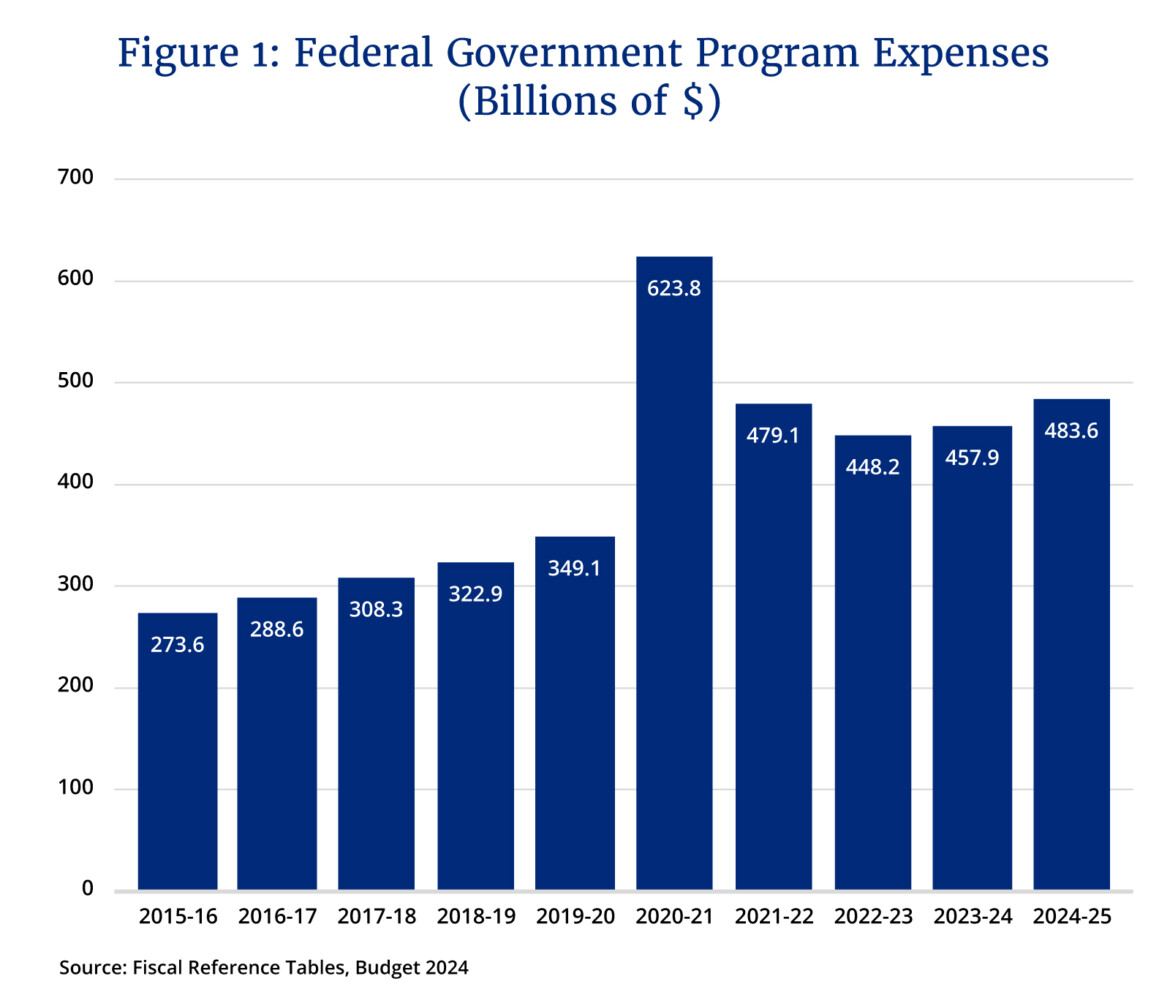

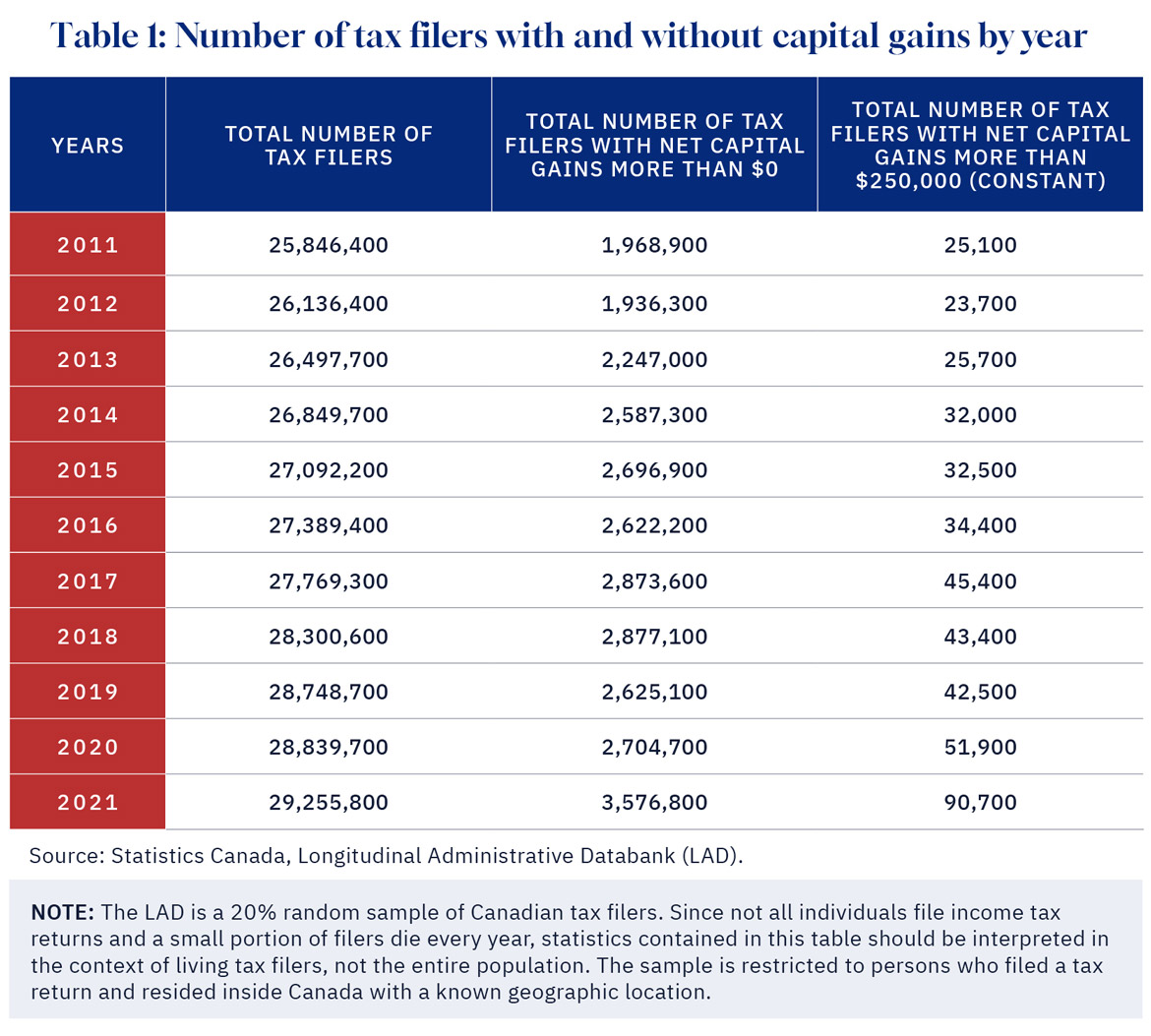

In Table 1, the total number of tax filers with and without capital gains is provided including those with more than $250,000 in capital gains. Averaged over the years, the number of tax filers with capital gains in excess of $250,000 is 40,664 per year, almost identical to the number of filers for 2025 forecasted in the 2024 budget.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

If the same tax filers repeatedly claimed more than $250,000 capital gains each year, one may conclude that only a small number of taxpayers are affected by the budget’s capital gains tax proposal. However, if large capital gains are realized only once or twice during a person’s lifetime or at death, many more Canadians, some with middle incomes, may be affected by the proposal on a lifetime basis. The extreme case would be tax filers who only appear once in their lifetime with capital gains of more than $250,000 in a particular year. In this instance, the total number of tax filers between 2011 and 2021 impacted by the proposal would be the sum of all filers in the third column of Table 1: 447,300.

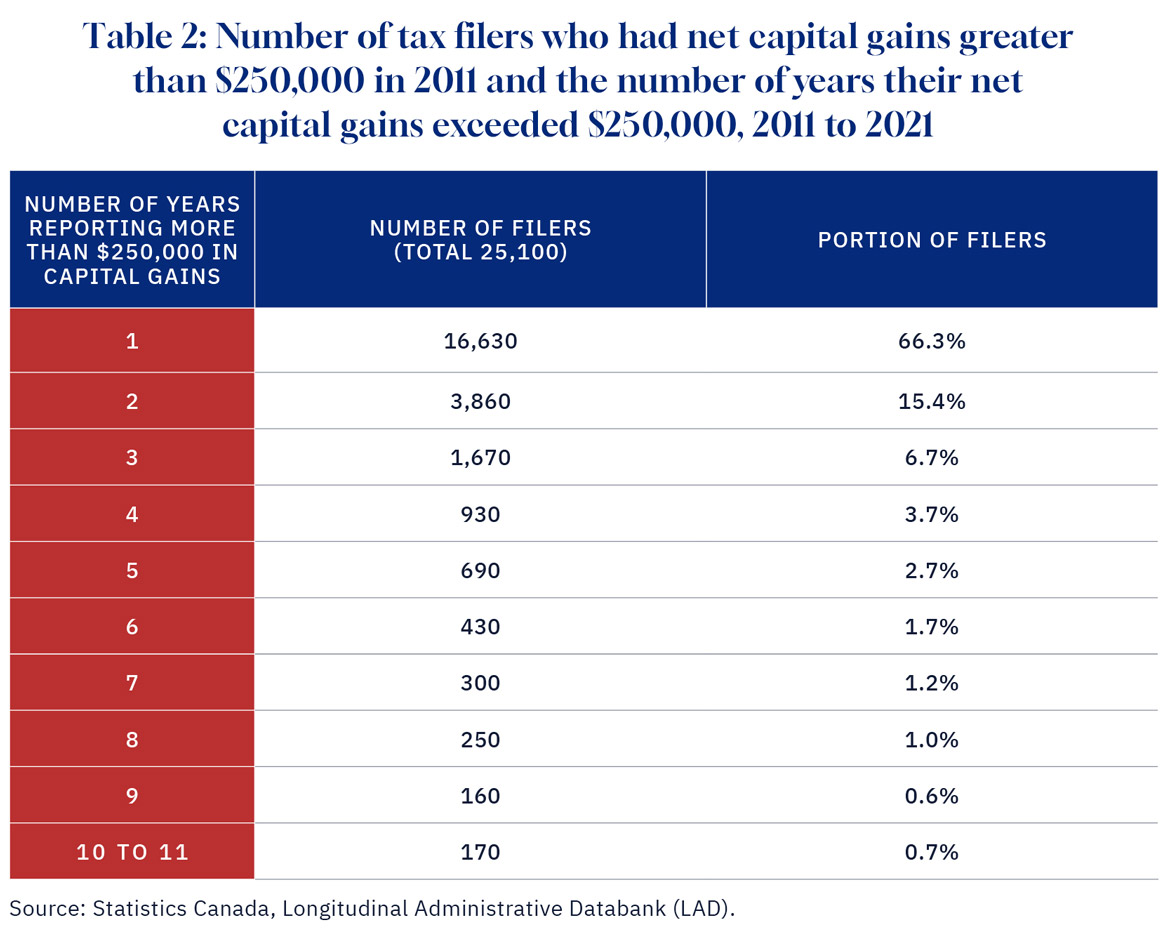

With some longitudinal data, I estimate how many years in which tax filers among this group report capital gains in excess of $250,000 to see whether it is once or more frequently. Table 2 provides the number of years in which tax filers who in 2011 reported capital gains in excess of $250,000 report it in total between 2011 and 2021. Almost two-thirds report capital gains only once. Another 15.4 percent report capital gains in two of the years. Barely one percent report capital gains in seven or more years. In other words, most tax filers report capital gains quite infrequently.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

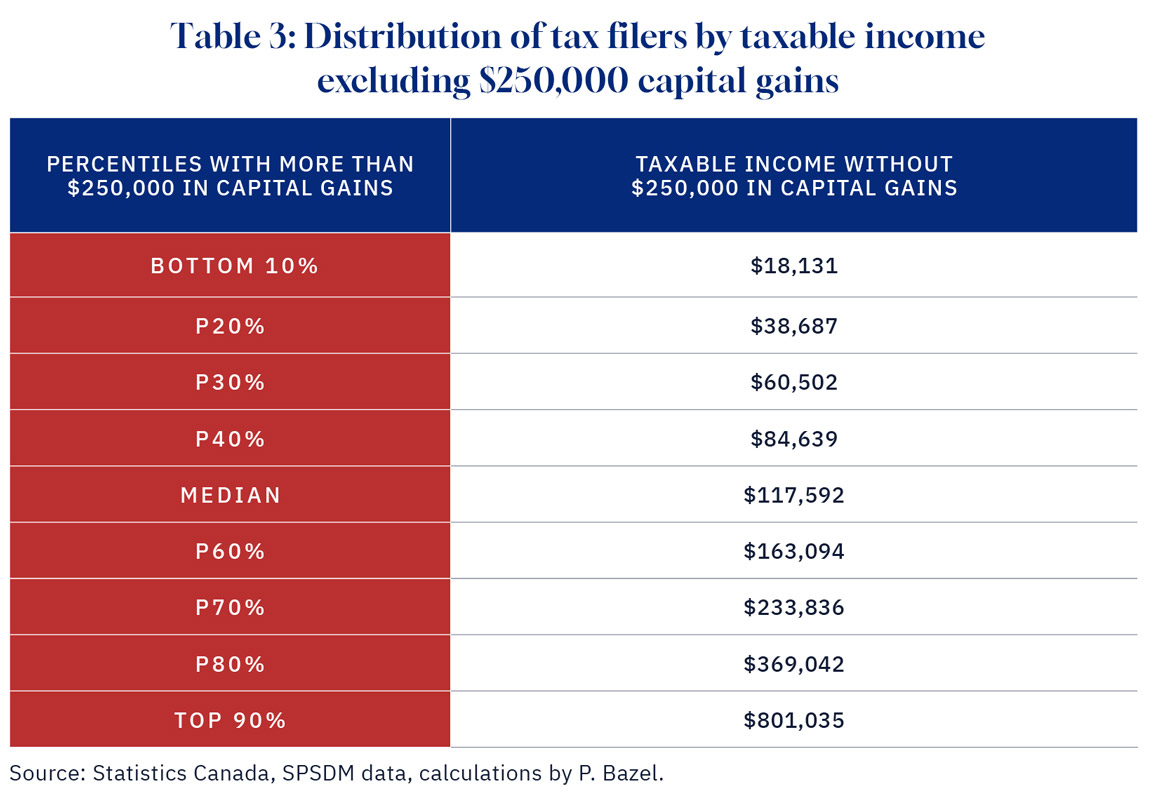

Of the taxpayers who claim more than $250,000 capital gains in a year, many would otherwise have middle-class or modest income. In Table 3, I provide the distribution of those affected taxpayers according to their non-capital gain taxable income (based on 2018 data of those with more than $250,000 in capital gains).

Without capital gains of more than $250,000, the top 30 percent of all tax filers (P70, P80, and P90) had other taxable income in excess of $233,836. However, 50 percent had non-capital gain taxable income below $117,592 with 10 percent having only $18,131. Based on Table 2, roughly 80 percent have large capital gains only once or twice, suggesting a good number of taxpayers experiencing capital gains in one year would otherwise have middle or modest income in other years.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Using the distribution of reporting years, a typical investor claims capital gains in excess of $250,000 1.84 times over the 11 years. Since those claiming large capital gains in multiple years are so few, I can assume that in each year, 22,088 (44,664 divided by 1.84) unique tax filers claim large capital gains. Table 2 is only a snapshot of those reporting $250,000 or more in capital gains in one year (2011). It does not reflect the population of taxpayers (generally 25 years or over) who report capital gains of less than $250,000 in that year but could report capital gains in excess of $250,000 in other years of their lifetime. Based on 22,088 unique tax filers estimated above, the number of taxpayers with large capital gains sometime in their lifetime is estimated to be 1.26 million.

As a share of Canada’s tax filer population, those impacted by the new capital gains proposal on a lifetime basis is 1.26 million or 4.3 percent of tax filers compared to the budget estimate of 0.13 percent.

Canadian-controlled private corporations

Many individuals hold savings in the form of a Canadian-controlled private corporation. As corporate capital gains will be subject to higher levels of taxation, the owners will be directly affected as they will receive lower dividends or realize lower prices for their shares when they choose to sell their equity held in the company. Once capital gains are realized in the private corporation, the deferral advantage for marginal taxpayers is eliminated with the refundable tax mechanism used for investment income. According to 2021 tax expenditure accounts, 1.112 million companies (98 percent of all corporations and 53 percent of corporate taxable income) are CCPCs. As in the case of individuals, corporate capital gains are infrequent as assets may be held for multi-years before they are disposed.

The 2024 budget estimates that 307,000 corporations in a year would have corporate capital gains but this includes public corporations. Taking 98 percent of this number, CCPCs affected by the change is equal to 300,860. Given multiple ownership of private corporations (such as family members or partners), the tax filers impacted by this provision will be much higher. On the other hand, some of the investors are already included in the number of affected individual investors on a lifetime basis.

A real estate sign is posted outside a home in Pointe-Claire, a city in Montreal’s West Island, Tuesday, May 7, 2024. Christinne Muschi/The Canadian Press.

Capital gain tax impact on the broad economy

Investors in both private and public corporations are affected by capital gains taxes to the extent that equity values are reduced, and investment is discouraged. Although the 2024 budget argued that capital gains taxes don’t affect business investment, that is only the case in which the valuation of large corporations is solely based on international equity markets of which Canadian savings have no discernible impact on the international cost of financing capital in Canada. That is clearly wrong in the case of corporate capital gains since a higher tax on such income will reduce the return to both domestic and foreign investors which would lower equity values.

From 2011 to 2021, corporate taxable capital gains were 6.98 percent of corporate taxable income. Increasing the inclusion rate from one-half to two-thirds increases the corporate capital gain tax rate from about 13 percent to 17.33. This is equivalent to increasing the aggregate corporate income tax rate by 0.3 percentage points, which would reduce corporate profits.

There is considerable evidence that capital gain tax increases affect the equity valuation of large corporations. Studies have shown that there is significant “home bias” with Canadians holding 52.2 percent of their portfolio in domestic assets even though Canada accounts for only 3.4 percent of global equity markets. Due to “home bias” and corporate capital gains taxes, several studies have shown that capital gain tax changes have had some impact on share prices of public corporations. In a Canadian paper by McKenzie and Thompson, personal dividend and capital gains taxes were found to be capitalized in Canadian equity prices, meaning that the assumption of a small open economy is not supported by the evidence.

Using these results, Milligan, Mintz, and Wilson examine the investment impact of reducing the capital inclusion rate for capital gains from two-thirds to one-half. They conclude:

“Even in a world with large tax-exempt entities (such as pension funds) and some degree of international capital mobility, taxes do appear to have an impact on the cost of capital for firms. We use the results of recent research to calculate that a reduction in the inclusion rate from 3/4 to 2/3 could increase investment by as much as 2%.”

Further, corporate capital gains taxes discourage acquisitions and mergers in markets, which protects management from takeovers. In a recent paper on mergers and acquisitions, corporate capital gains taxes were found to reduce acquisitions by $1.1 billion annually in Canada, resulting in an economic loss of annual synergy benefits equal to $300 million each year.

Capital gains taxes therefore have broad effects on the economy. Corporate capital gains taxes will suppress equity values impacting investors including pension funds and other saving deriving dividend and capital gains income from Canadian corporations. Both corporate and personal capital gains taxes will reduce business investment and therefore fall on capital owners or be shifted onto consumers through higher prices or workers as lower wages. Governments will lose other tax revenues as well.

Given capital gains taxes, especially corporate capital gains, can reduce equity values and business investment, many Canadian shareholders would be affected. In 2021, 4.74 million tax filers received taxable dividends from Canadian corporations, representing 15.8 percent of all filers. Adding equity valuation impacts on pension plans, registered saving plans, and real estate, an even larger number of taxpayers are affected.

Key takeaways

The 2024 budget claims that only 0.13 percent of tax filers are affected by the increase in the tax rate on capital gains in excess of $250,000 is badly off the mark. On a lifetime basis, many taxpayers are affected since they will pay capital gains taxes on infrequent asset disposals. Based on some longitudinal data, I estimate that 1.26 million individuals, or 4.3 percent of taxpayers, will be affected.

Even this estimate is an understatement. Capital gains taxes, especially at the corporate level, will impact equity values and reduce both dividends paid to shareholders as well as the capital gains on disposing equities held in private and public firms. Overall, 4.74 million individual investors in Canadian companies will be affected, representing 15.8 percent of all filers. Other Canadians will also be affected as equity held by pension plans, registered retirement plans and other non-registered saving in equity or real estate can be impacted too.

To the extent that capital gains taxes discourage investment, the broader economy is affected including worker incomes and government reliant on tax revenues generated by business activity. This was the point that Adam Smith made 250 years ago. The federal government should have paid attention to his arguments.

Recommended for You

Ginny Roth: J.D. Vance, Pierre Poilievre, and how they slice their economic pie

David Polansky: As President Biden leaves the race, will the Democratic Party hodgepodge hold?

RCMP spending to protect MPs may have risen 112% since 2018, as Canadian politicians face greater rise in threats

Trevor Tombe: Canadians are paying billions in hidden taxes on new homes