Outside of 2020, when we were in lockdown, 2024 has been the worst year on record for teenagers to get a summer job, whether as a cashier at a convenience store or selling ice cream.

Despite the challenges teenagers are currently having in the job market, the number of temporary foreign workers approved for those same positions has never been higher, thanks to the federal government’s deregulation of the temporary foreign worker program in 2022.

If we rewind to early 2022, Canada’s unemployment rate was falling fast, dropping from 6.5 percent in January to 4.8 percent in July, and job vacancies were at an all-time high. Inflation was at the highest rate in 40 years and continuing to rise, peaking at 8.1 percent in June 2022. In response, less than two weeks after signing the Supply and Confidence Agreement, the Liberal government deregulated the temporary foreign worker program, with the largest changes coming to the low-wage, non-agricultural stream. This allowed companies to bring in non-agricultural workers to jobs that pay under the median provincial wage.

These changes lifted a restriction that employers in high-unemployment regions (defined as six percent unemployment or higher) could not hire low-wage workers in some occupations. It also increased the proportion of low-wage temporary foreign workers a company could employ from 10 percent to 20 percent, with some industries, like accommodation and food services being given a 30 percent cap.

In one sense, the changes were highly successful, as employers took advantage of the new rules. The Globe and Mail’s Matt Lundy found that the number of positions approved in the low-wage stream more than doubled between 2021 and 2022. Inflation came down, in part because labour costs stopped increasing, as workers lost their leverage to negotiate higher wages.

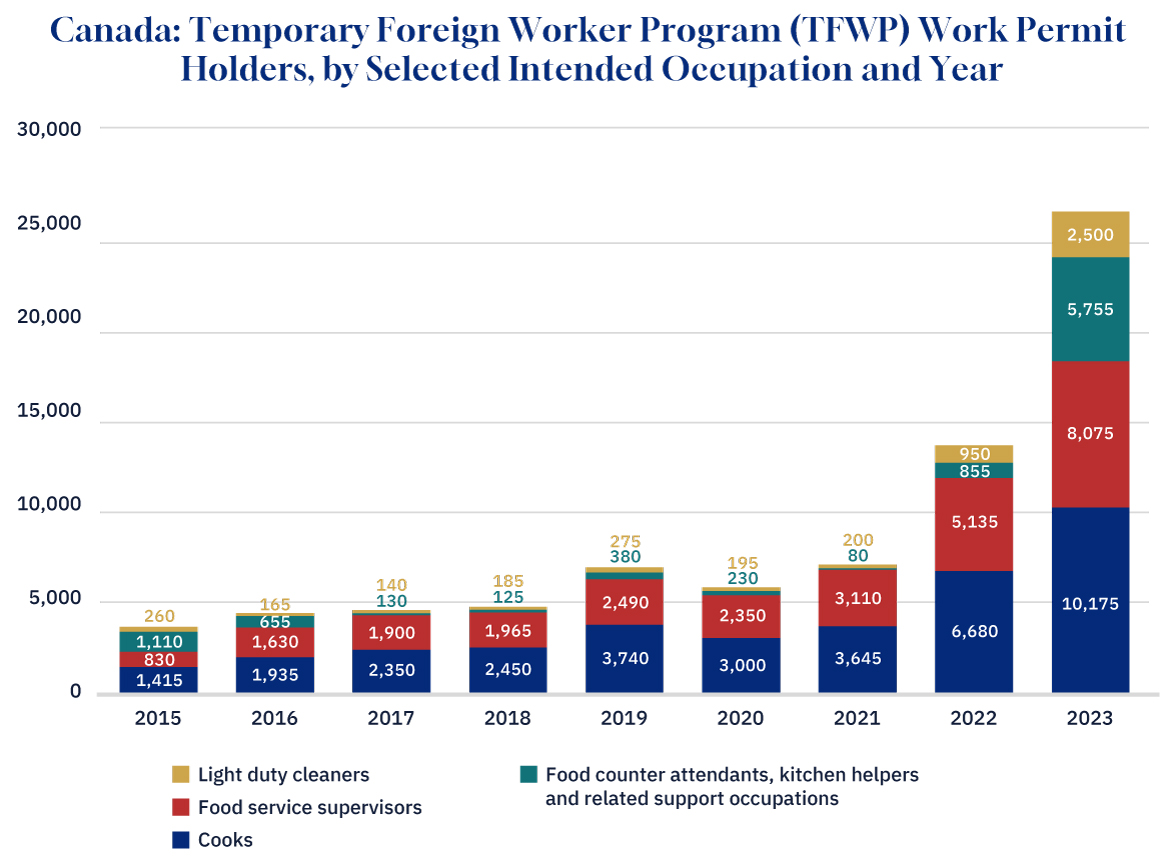

Numbers have continued to grow since then in a handful of lower-wage professions. A review of the data reveals some low-wage occupations have experienced astronomical increases, such as “food counter attendants” which rose from 125 in 2018 to 5,755 in 2023. The four cleaning and food preparation occupations shown below have doubled each of the last two years, and Q1 2024 saw an over 40 percent increase relative to Q1 of 2023.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

The federal government provides data on the companies granted permission to bring in a temporary foreign worker after they have made their case that a Canadian or permanent resident is not available to do the job (known as a Labour Market Impact Assessment). An anonymous Reddit user created a website, LMIA Map, that provides a detailed map of the federal government’s Labour Market Impact Assessment (LMIA) data. It reveals that employers in practically every community in Canada have an employer that has been granted permission to bring in low-wage workers in these occupations, not just in resort towns where seasonal labour shortages could be expected.

It is extremely implausible that Burger World in North Bay, Ontario, or Harvey’s in downtown Winnipeg, cannot find Canadians willing to work as food counter attendants. A Bloomberg report found that Tim Hortons locations were permitted to bring in 714 temporary foreign workers in 2023, up from 58 in 2019.

The growing number of low-wage temporary foreign workers is problematic for at least two reasons. The first is that it reduces job opportunities, particularly for young Canadian workers, while also suppressing wage increases.

Creating a new Canadian underclass

The Liberals and NDP both once understood this, as they were rightly critical of the increases in low-wage temporary foreign workers that happened under the Harper government. This led to Jason Kenney, then-Immigration minister, substantially scaling back the program.

In 2014, Justin Trudeau called out the governing Conservatives for allowing the temporary foreign workers program to expand while ignoring its “impact on middle-class Canadians: it drives down wages and displaces Canadian workers.” He wrote that it needed to be “scaled back dramatically over time.”

NDP MP Nathan Cullen suggested that the Conservatives “brought in over 350,000 temporary foreign workers a year, which has also helped to suppress wages in Canada, according to various studies from very Conservative think tanks that have looked at it.”

In 2014, Liberal MP Scott Brison noted that “[S]ome economists are linking the growth in the number of low-skilled temporary foreign workers under the Conservatives with higher youth unemployment in Canada and wage suppression for Canadian youth.” The Liberals and NDP were right to be concerned a decade ago; I was one of those economists Brison was citing.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau shakes hands with Goodyear employees at the plant in Napanee, Ont., Aug. 12, 2024. Justin Tang/The Canadian Press.

It is important to recognize that the increase of a pool of industry-specific talent in a location does not necessarily have to reduce domestic employment or suppress wages. In some cases, it could even raise wages for existing workers.

Take Canada’s tech industry, for example. While a sudden increase in the number of tech workers does increase the supply of those workers, it can also increase the demand, as the local tech ecosystem is that much stronger, attracting foreign investment and encouraging start-ups.

This logic does not hold, however, for coffee shop workers and convenience store cashiers. A large increase in food counter attendants does not create the conditions for a local fast-food cluster to emerge. The size of the market and the number of jobs is almost entirely a function of local demand for coffee and donuts. While a temporary foreign worker boom will increase the population and thus slightly increase the demand for those products, it will in no way offset the increase in labour supply. The number of people looking for these positions will rise faster than the number of positions. You end up creating a Canadian underclass of service workers.

Young Canadian workers hardest hit

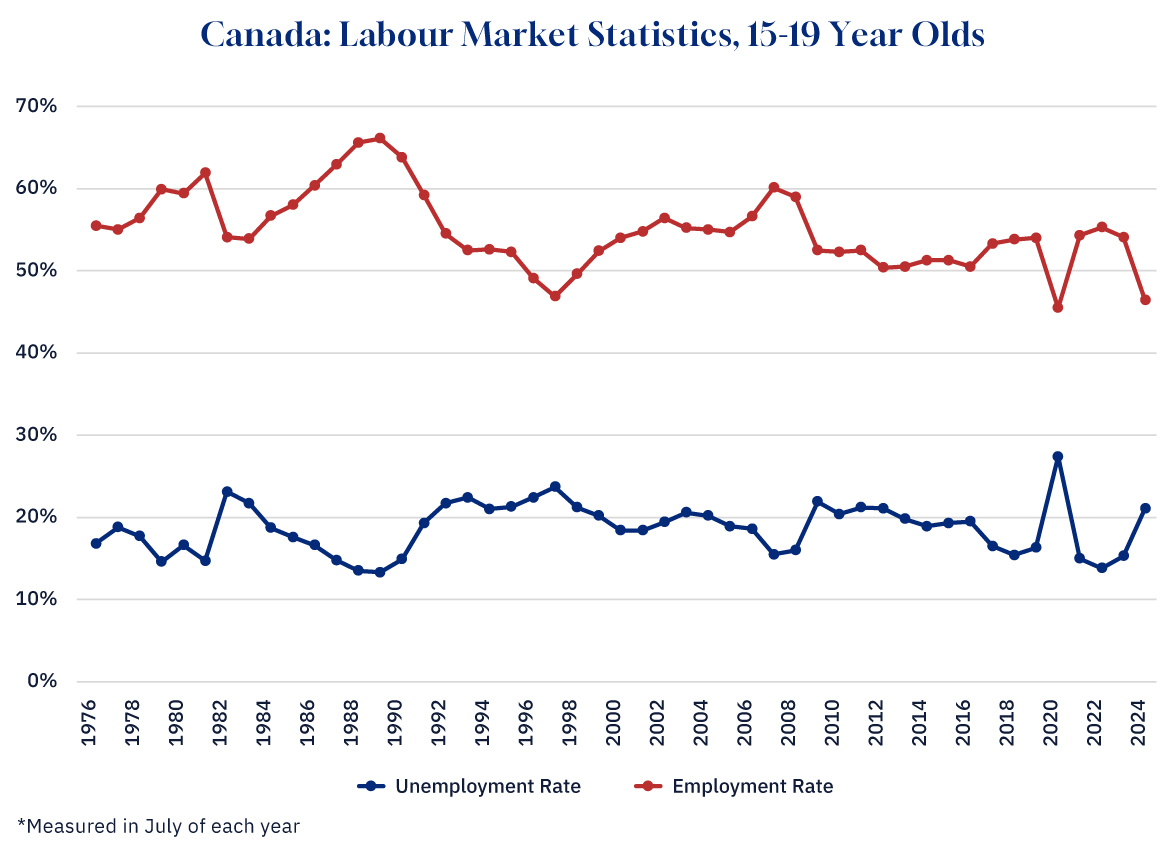

Young Canadian workers are having an exceptionally tough summer. Canada’s Labour Force Survey shows some very worrying trends. One is the employment rate, which measures the proportion of a population that is currently employed.

Last month, the employment rate for 15-19-year-olds was the second-lowest on record, only slightly ahead of the lockdown year of 2020. The rate is now 46.4 percent, whereas it has consistently been between 50-60 percent (outside of 2020) for the last 25 years, averaging 54 percent.

If Canada’s employment rate had remained at 54 percent, which it was in 2019 and 2021, an extra 200,000 teenagers would have a job this summer. These are jobs they need badly to attend college and university and pay for the incredibly high rents in college towns across Canada.

A “Now Hiring,” sign is displayed on a business in Montreal, May 30, 2023. Christinne Muschi/The Canadian Press.

The unemployment rate, which measures the proportion of the labour force that does not have a job but is actively looking for one, is at levels experienced after the 2008 global financial crisis.

This surge in the unemployment rate, while pronounced, is not as dramatic as the fall in the employment rate. What is likely happening is that many teenagers have given up looking for work this year, recognizing the limited opportunities. This year, line-ups of people looking for jobs have gone viral on Reddit and TikTok. One prominent example is the videos showing the 37,000 people who applied for a job at the Canadian National Exhibition (CNE) this summer, up from 18,000 last year. It should come as no surprise that young people are giving up hope.

Occasionally, you will hear some commentators suggest it is necessary to bring in low-wage temporary foreign workers, as there is somehow no one in Canada who is willing to work at Tim Hortons or Dairy Queen.

But, if that is the case, then how can we explain the 37,000 people lining up for a job at the CNE, or the 1,000 people lining up for the minute chance to obtain one of two open jobs at a Kitchener Dollar Tree? Or the massive line-ups to any job fair in the Greater Toronto Area, including the 500 applicants desperate to work at a grocery store in Brampton? It is highly implausible that every single one of these individuals is not capable of working an entry-level job. But if that is the case, should we not be trying to solve that skills gap, rather than papering over it by bringing in temporary foreign workers?

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

We cannot pin all these poor labour market outcomes on the 2022 deregulation of the temporary foreign worker program. The drop in Canada’s youth employment rate is just too large relative to the number of workers approved through the temporary foreign worker program. A large increase in the population of 18-to-29-year-olds, largely from the international student boom (who are not counted as part of the temporary foreign worker program) coupled with a weakening economy, are also large contributors to the problem. But the boom in temporary foreign workers is making a bad situation worse.

The blame, of course, should not be put on the foreign workers themselves but rather on the federal government that allowed businesses to bring them in—and the businesses themselves which chose to hire TFWs over eager Canadian workers already in the country.

“Contemporary slavery”

The second problem with the low-wage stream of the temporary foreign worker program is the exploitation of these foreign workers, with the United Nations recently classifying Canada’s program as a “breeding ground for contemporary forms of slavery.” In a scathing report, Tomoya, the UN special rapporteur on contemporary forms of slavery, noted that temporary foreign workers are on closed work permits, leaving them unable to change employers. This means the loss of their job could lead to deportation and homelessness.

The program also leads to “debt bondage among many migrants as they may pay large amounts of money to recruitment brokers in their countries of origin.” Because of this debt bondage and closed permits, these workers are left vulnerable to abuse and exploitation.

We must embrace a strong economy

Each of the streams of the temporary foreign worker program, including the high-wage stream and the agricultural stream, are in dire need of reform. The low-wage stream should be abolished as soon as reasonably possible. There is simply no justification to bring in low-wage workers when so many young people in Canada are struggling to get ahead.

Yes, once in a while, like in 2022, labour markets will get tight and employers will have trouble finding workers. But we should embrace it, not fear it. Tight labour markets allow wages to rise for low-income workers and spur investments into automation, which leads to higher productivity.

Canada will continue to lag behind in technology investment, productivity, and wage growth if we continue to believe that a strong economy is a problem that must be solved by importing and exploiting vulnerable international workers.