The past installments of this Defence 2.0 series have focused on broader issues surrounding the Department of National Defence, the military, and the role of Parliament. This week will focus on a specific area in dire need of reform: procurement.

The war in Ukraine has made it abundantly clear that procurement matters—a lot. The ability to acquire capabilities quickly and at a scale that can make a difference on a battlefield has consumed the discussions at NATO for the past two years. Perhaps the most important realization is that procurement strategy is an integral part of an overall war strategy. The ability to ensure that your forces are able to acquire cutting-edge capabilities at production scales commensurate to actual usage is vital. Yet in Canada, this entire debate has barely made a ripple in the political discourse.

Canada needs a procurement system that is fit for purpose, yet what it currently has is anything but. The examples of missed deadlines and massive overspending are, unfortunately, too numerous to succinctly recount.

The failure to replace equipment on time and budget with capabilities commensurate to the threats that Canada faces has had serious consequences for the armed forces and the country’s security writ large. On the whole, our aging equipment base is largely obsolete compared to what adversaries field, and it also drives up costs as their maintenance requirements increase. It contributes to the many other issues that the Armed Forces personnel face like surrounding quality of life and further saps morale and retention.

A serious approach would require a major change to the system, with an eye to addressing, either immediately or eventually, the major issues that afflict military procurements.

Unfortunately, the issues afflicting the system do not neatly reside within the Department of National Defence. Rather, five different departments are substantially involved in procurement. Alongside DND, they include Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC), Industry, Science and Economic Development, the Treasury Board, and the Justice Department. Part of the problem with this arrangement is that while PSPC is nominally the “lead” department, in practice it is more like a first among equals. The lack of clearly designated authority effectively allows each department to wield a veto over the process until its particular concerns are addressed in some way.

Given the widespread issues that currently afflict procurement, anything less than a major overhaul is highly unlikely to have any serious impact. The existing system has been incrementally developed over the past 40 years, and a large amount of policy and process deadwood has been allowed to accumulate. A clean break is required.

Fundamentally, Canada should create a new agency responsible for defence procurement, one that is empowered to make adjudications between competing procurement priorities. This is not a new proposal. The Liberal Party had it as part of its 2019 campaign plank, but it never implemented the promise after the election. Moreover, many of these plans are fairly superficial in their forethought: they are predicated on the view that drawing new lines and boxes on an org chart would be sufficient to reform the procurement system. However if the reorganization will essentially recreate the existing dynamics in the new agency, it will have little to no impact.

The key opportunity that creating a dedicated defence procurement agency provides is the ability to introduce new systems, processes, culture, and even personnel to achieve better outcomes.

The overriding objective of the reorganization should be to focus on adopting a single point of accountability model for procurement. The U.S. government instituted a similar model for defence acquisitions after facing similar challenges to Canada. The benefits have been clear. It creates clear lines of authority, where one individual is charged with the authority for overseeing all aspects of a given program—and, crucially, is given the required resources to see it through.

The first step would be to aggregate as much of the responsibility into the new agency as possible. Instead of having five departments/agencies involved in a procurement, a single agency would be responsible for managing the various policy objectives for a procurement internally.

This would replace the current system of diffuse responsibility that pervades the defence procurement system today, which effectively requires unanimity among major players to advance a project. This approach does not necessarily mean that other objectives such as economic development and value for money are discarded. Arguably the current system does a poor job of ensuring those objectives are met anyway. Rather, programs using this system take the objectives into account and develop a policy that balances various trade-offs. In some cases, it discards the idea that every program can meet every objective and prioritize specific outcomes, such as urgent delivery, best value, best capability, or domestic industrial development.

Properly implemented, this approach can be quite flexible, which is vital for the varied nature of procurement programs today. Many, if not most programs, are heavily reliant on embedded electronic capabilities, including in the cyber domain. which are fundamentally different to manage from traditional physical systems. Similarly, the push for greater interoperability between capabilities requires a more robust approach to acquisition than what currently exists.

It should be noted that not all functions can be folded into such an agency. The Treasury Board’s oversight functions would likely remain independent, and the individual services would remain as the initiator of programs and drive their requirements as well. Nevertheless, consolidating program management as much as possible would greatly improve outcomes.

For the single point of accountability system to work, program managers require an experienced, highly technical staff supporting them to achieve success. They can identify potential issues before they start, devise policies to mitigate risk and costs, and generally help shepherd programs to achieve the best possible outcomes. However, achieving this requires the government to address its current challenges with retaining technical staff within DND.

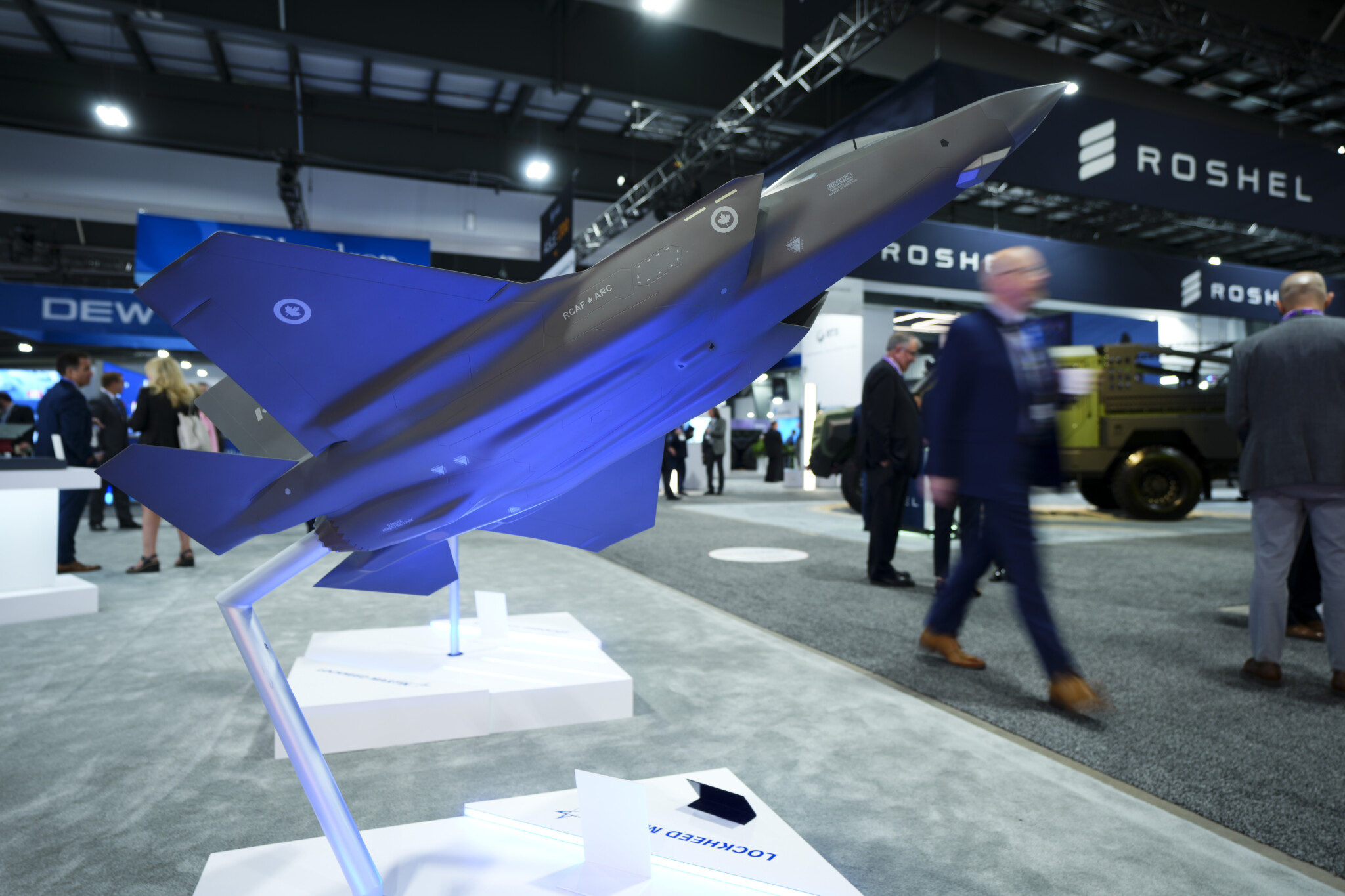

People attend the Canadian Association of Defence and Security Industries annual defence industry trade show CANSEC in Ottawa, May 30, 2024. Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press.

At present many subject matter experts, after decades of services either in uniform and/or as part of the public service, have left to work as contractors for government—often in the same role they did before. There are a variety of factors behind the decision to become a contractor, but the lack of compensation and resources as well as difficult working conditions are common refrains.

What the creation of a defence procurement agency needs to do is cultivate and concentrate these unique sets of individuals, then try to keep them “in-house” for as long as possible. One would hope that the new working environment would work to retain many individuals, but it is more than that. Their technical expertise often would allow them to fetch much higher salaries in the private sector.

The government has one more tool to address this challenge. It involves a rarely used provision called Separate Employer Status (SES). This allows the organization to manage its collective bargaining, staff relations, and compensation matters independently from the government of Canada, in order to better manage its own human resources. It is generally employed in places where the staff situation is unique and requires greater flexibility than in the rest of the public service. A 2023 study on reforming Global Affairs Canada recommended that the department utilize SES because of its heterogeneous workforce that had a diverse array of roles. That fits the description of other departments that currently operate under the status: CSIS and the Canada Revenue Agency.

Considering the highly technical nature of defence procurement and the premium skilled professionals that operate in this field command in the private sector, SES could be a key tool to attract and retain these key individuals. That flexibility would allow the agency to provide more attractive compensation for the unique workforce it manages on a day-to-day basis. While this may come under some criticism, the widespread use of former officials as contractors is just a costlier, less effective approach to achieve the same ends.

It is important to note that this transition will not be easy. It’s quite likely that the public service would object to a number of aspects of the shifts, especially where the SES is involved. It will require significant legal effort and multi-party political support to establish. Several of the departments will object to having their responsibility hived off to a new Agency, but that can be worked through if the political will exists.

And must be worked through—Canada has been exceedingly fortunate its military has not been seriously called on in an emergency in quite some time. But fortune is not a strategy, and as things stand the country finds itself extraordinarily unprepared to respond in any major way if needed. We must act now to fix our procurement processes while we still can and before it’s too late.