When the history of how Canada struggled to address climate change is written, a cranky chapter should be aimed at the managers of the Canadian Revenue Agency (CRA).

This for their unhelpfulness on the climate change file.

And then some stick should also be applied to progressive politicians and strategists like me who chose to live with that.

But before I explain that, a little family history.

When I was a child, I liked to play in our living room in the little bungalow I grew up in, bathed, as it was, in warm afternoon sunlight. My mother would usually be sitting on the sofa under our big picture window. It was fun (but possibly not healthy for young lungs) to watch her cigarette smoke eddying in the light.

Periodically she would open her baby bonus cheque in that living room—a little help from the government of Canada to bear the cost of three sons. That was always a happy day for my mother because that cheque was the only income she ever saw addressed directly to her (she was a homemaker in the classic early-1960s style). She deposited those cheques in her own bank account—“my money” as she would always happily say. She spent it all on us.

So then, some years later, in Premier Rachel Notley’s office in Alberta (which was also often bathed in beautiful sunlight), we chose to adopt carbon pricing on the B.C. model to address climate change.

We believed there were many reasons to do this.

Harmonizing with B.C. would promote consistent policy in Western Canada.

Most of the principal Alberta energy industry CEOs at the time supported a B.C.-style economy-wide carbon pricing so that their industry would not be vilified as the only cause of carbon emissions.

Leading economists at the time argued that economy-wide carbon pricing was the least economically damaging policy tool to address the issue.

And—importantly—it seemed like a way to achieve an all-party political policy consensus on climate change that would survive changes of government.

Most Canadian conservatives had finally stopped disputing the reality of climate change and its causes. A center-right government under Gordon Campbell had introduced carbon pricing in B.C. And leading conservative voices like Preston Manning had participated in the “Eco-Fiscal Commission” (funded in part by Alberta-based energy producers) to think through and endorse this approach.

The problem with an “economy-wide carbon price” was that it would impose direct costs on low-income families. A model to address this is present in federal HST/GST rebates. So we wrote that into our plan—low- and middle-income families would get a rebate. They’d get the “nudge”—the price signal that the time has come to reduce carbon emissions—but they’d also get the money back so they weren’t the poorer for it.

We were imagining this rebate as a cheque. What we didn’t appreciate was how inflexible the tax administration system truly was.

Alberta (like all Canadian provinces other than Quebec) has long delegated its tax administration to the CRA, and (as I remember it) Alberta officials reported that not only was the CRA no longer technically equipped to deliver physical carbon levy rebate cheques, but also, that they refused to even discuss the matter. All such payments had to be delivered through direct zero-visibility electronic bank transfers because that is what is inexpensive and convenient for the federal government and its tax agency.

It was a very serious mistake indeed to accept this.

We should have printed our own cheques, in red-bordered envelopes illustrated with the provincial flag, and we should have pre-paid the rebate.

But we didn’t.

And we did not find an all-party policy consensus that climate change is real and that the best way to deal with it is through price and market mechanisms designed by conservative economists.

Instead, we have laid the table for a Trump-like populist campaign messaging—“Axe the Tax”—delivered every day in Ottawa by His Majesty’s Loyal Official Opposition.

Notwithstanding the Conservative Party’s disciplined message or even the Parliamentary Budget Office’s contested research, most Canadians actually get the consumer carbon fully rebated. However, those “most Canadians” don’t have that rebate in their daily lived experience.

And there’s more. As it turned out, many people who are aware of those rebates still don’t support them. In focus groups I sat through as this policy played out, many Albertans told us they’d rather the revenues from carbon levies be used to improve health care and education, to build public transit, or to invest in renewables.

“Why the hell are you collecting it and then giving it back? What’s the point?” they said.

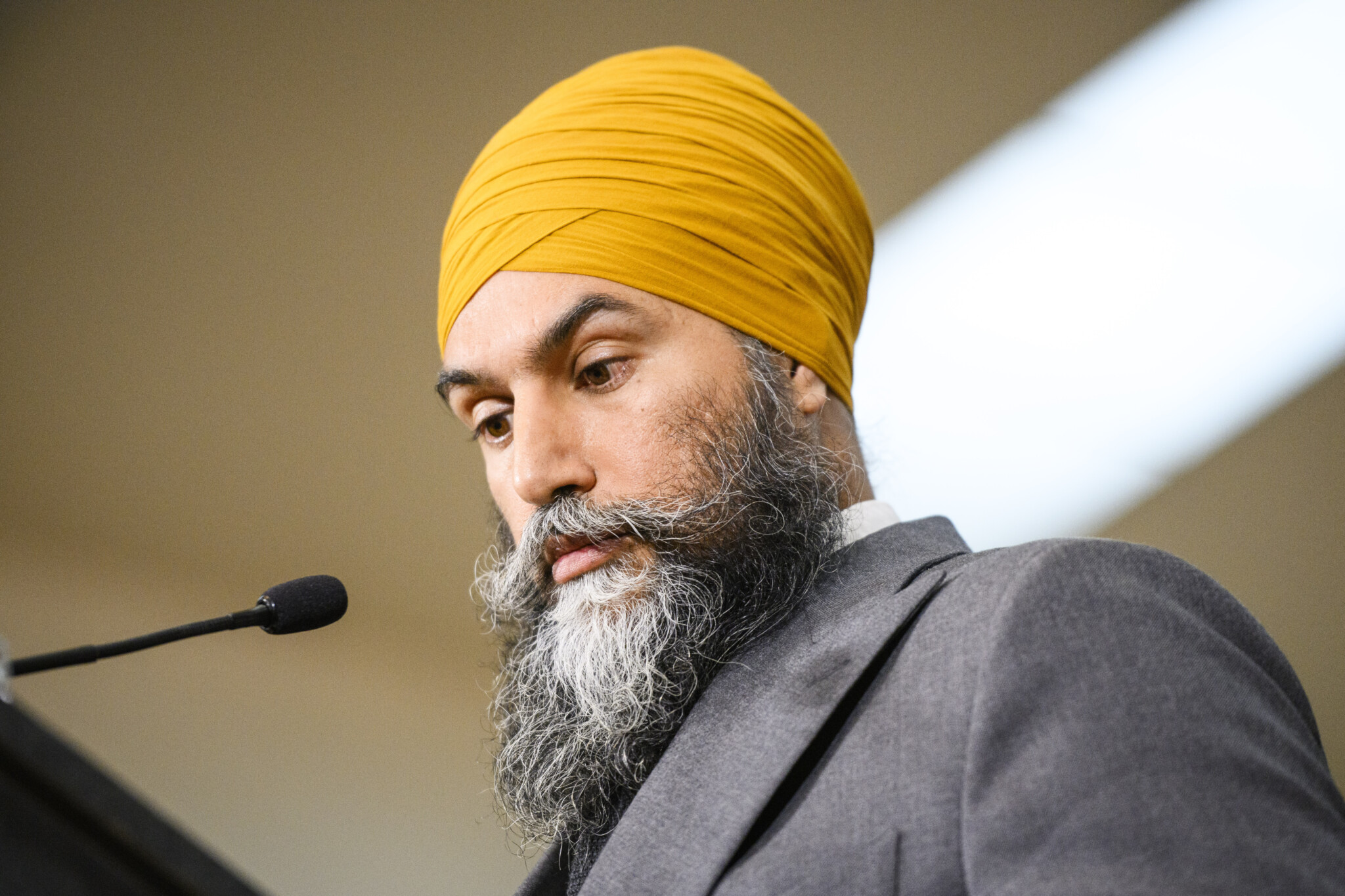

All of this is, I believe, why the federal NDP recently took a step away from the consumer carbon levy and said they’ll present their own plan in due course.

How material a problem would that be?

The Canadian Climate Institute figures the consumer carbon levy (basically, consumer fuel levies) is supplying about 8 to 9 percent of the solution we need.

That’s not nothing. But it’s not a comprehensive retreat to climate denial, either.

Is stepping away from a consumer carbon levy a policy defeat?

Yes, for everyone who believes in market-based solutions to public policy challenges through price signals.

For social democrats, on the other hand, this is an opportunity to work up more direct regulatory solutions.

It’s an odd moment in Canadian governance, in other words. A moment for social democrats to say to conservatives: “You don’t like your own policies, even when they had an all-party consensus? Ok. Have it our way.”

What is not going to happen is wishing away climate change with alliterative slogans. Anyone who believes that should drive the Jasper Parkway north from Calgary to the Jasper National Park Icefield and go look at what is happening to Canada’s glaciers. Then keep going to Jasper itself and look at what the coming wildfires will do to cities and towns in the Boreal Forest across Canada. Climate change is real. It must be addressed. Including by us in Canada. One way or another.