In each EconMinute, Business Council of Alberta economist Alicia Planincic seeks to better understand the economic issues that matter to Canadians: from business competitiveness to housing affordability to living standards and our country’s lack of productivity growth. She strives to answer burning questions, tackle misconceptions, and uncover what’s really going on in the Canadian economy.

An educated workforce is central to a strong economy, and it is one of Canada’s greatest strengths. Nonetheless, many worry that Canada is not sufficiently funding its public education system.

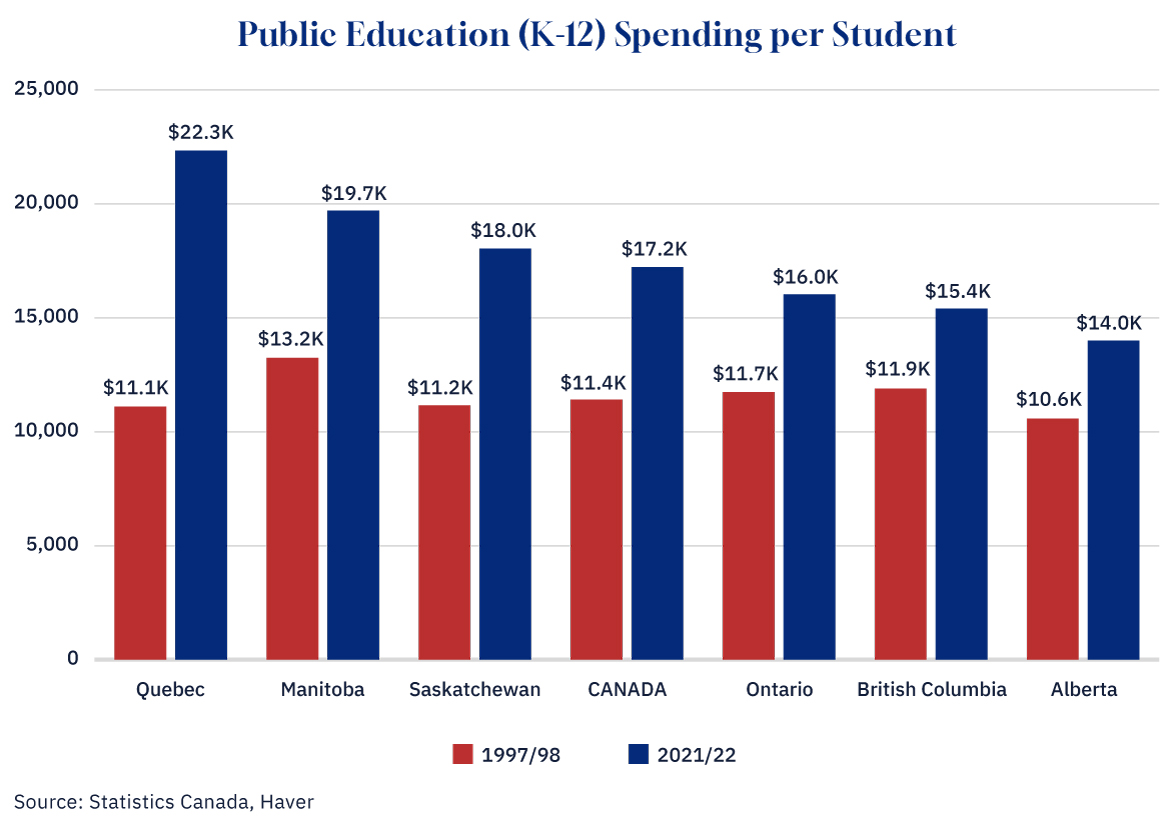

In fact, spending on public education (K-12) has grown considerably and is up across all large provinces. Since the 1997-98 school year (the earliest year for which we have comparable student data), total public school spending has grown by 47 percent (accounting for inflation).

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Per student, spending is up even more. This is because, despite Canada’s strong population growth over this time (around 30 percent), the student population has actually shrunk. There are fewer school-age children in every province except one: Alberta. Thanks to its younger population and in-migration, the student population in Wild Rose Country is up nearly 30 percent.

Nonetheless, all provinces are spending more per pupil, including Alberta. Canada-wide, dollars spent per student have grown from an average of $11,000 a couple of decades ago to $17,000 as of the latest data.

Growth hasn’t been completely consistent over this time. In many provinces, spending growth was especially lively in the early 2000s and has been more modest since. But the general trend has been up.

Have funding increases brought better results?

The good news is that extra funding seems to have afforded school districts more teachers. There are almost 53,000 more full-time educators today than there were back then. As such, the student-teacher ratio, arguably an important factor in student experiences and outcomes, looks much better than it did.

But its effect on student outcomes is less clear. While standardized assessments certainly don’t capture all that a student learns, test scores are nonetheless one of the more readily quantifiable and comparable “outcomes.” Despite increased spending and more teachers per student, global assessments like the PISA, which tests students on key subjects like math and science, show that results across Canada have actually deteriorated.

At the same time, students in provinces that spend the most do not necessarily perform the best. Alberta spends less than other large provinces but excels in student outcomes.

Of course, there is more to the story. The decline in international test scores is a trend seen across much of the developed world, especially since 2009. While there are many theories (with the pandemic likely affecting results more recently), many have argued that student needs have grown, in which case funding increases could be necessary (for more teacher assistants, let’s say) simply to maintain the same student outcomes of the past.

Whatever the case, in its defence, Canada continues to show stronger outcomes than many of its peers. But it’s worth a conversation on what is needed to reverse the downward trend.

A version of this post was originally published by the Business Council of Alberta at businesscouncilab.com.