Quick, name the nine justices of the Supreme Court of Canada. You may know one of them—the tireless self-promoter Chief Justice Richard Wagner—but I suspect that the vast majority of readers will draw a blank on any names beyond his, and I guarantee that even fewer will know much about the hundreds of lower court judges who make important decisions that affect our lives every day. That’s a problem. Citizens in democratic societies should be able to hold accountable, or at least know the names of, the people who exercise state power, especially when that power is exercised over matters of life and death.

British citizens know the name Kim Leadbeater very well by now. She is the Labour MP who introduced a private member’s bill to legalize assisted suicide and establish procedures through which the U.K.’s National Health Service could deliver it. Much of British public life has been consumed over these past few weeks with vigorous debates on Leadbeater’s bill.

MPs, commentators, and ordinary citizens have been discussing whether it sufficiently balances individual autonomy with the sanctity of life, and asking if a state-run suicide system can ever be truly non-coercive in an atmosphere of stretched health-care budgets and tacit—or not so tacit—societal pressure to “not be a burden.”

Last Friday, the British House of Commons voted to advance the bill through second reading by a vote of 330 in favour and 275 opposed. The bill will now move to committee for a more detailed review before it continues through third reading, and, if passed then, onto the House of Lords for still further debate.

Strikingly, whether Leadbeater’s bill will become law is still hard to predict. Support for and opposition to assisted suicide has come from all major parties. For Canadians, it’s been remarkable to see that some of the most compelling speeches in opposition were made by MPs on the Left of the governing Labour Party.

Moreover, some MPs who voted to advance the bill at second reading have already expressed concern that there will not be enough time to properly discuss or include safeguards in the bill and said they might still vote against it at third reading. Others have argued the debate is being rushed, with one MP lamenting that the U.K.’s Parliament spent over 700 hours debating a ban on fox hunting, but has only spent five hours debating whether and how to assist suicides for human beings.

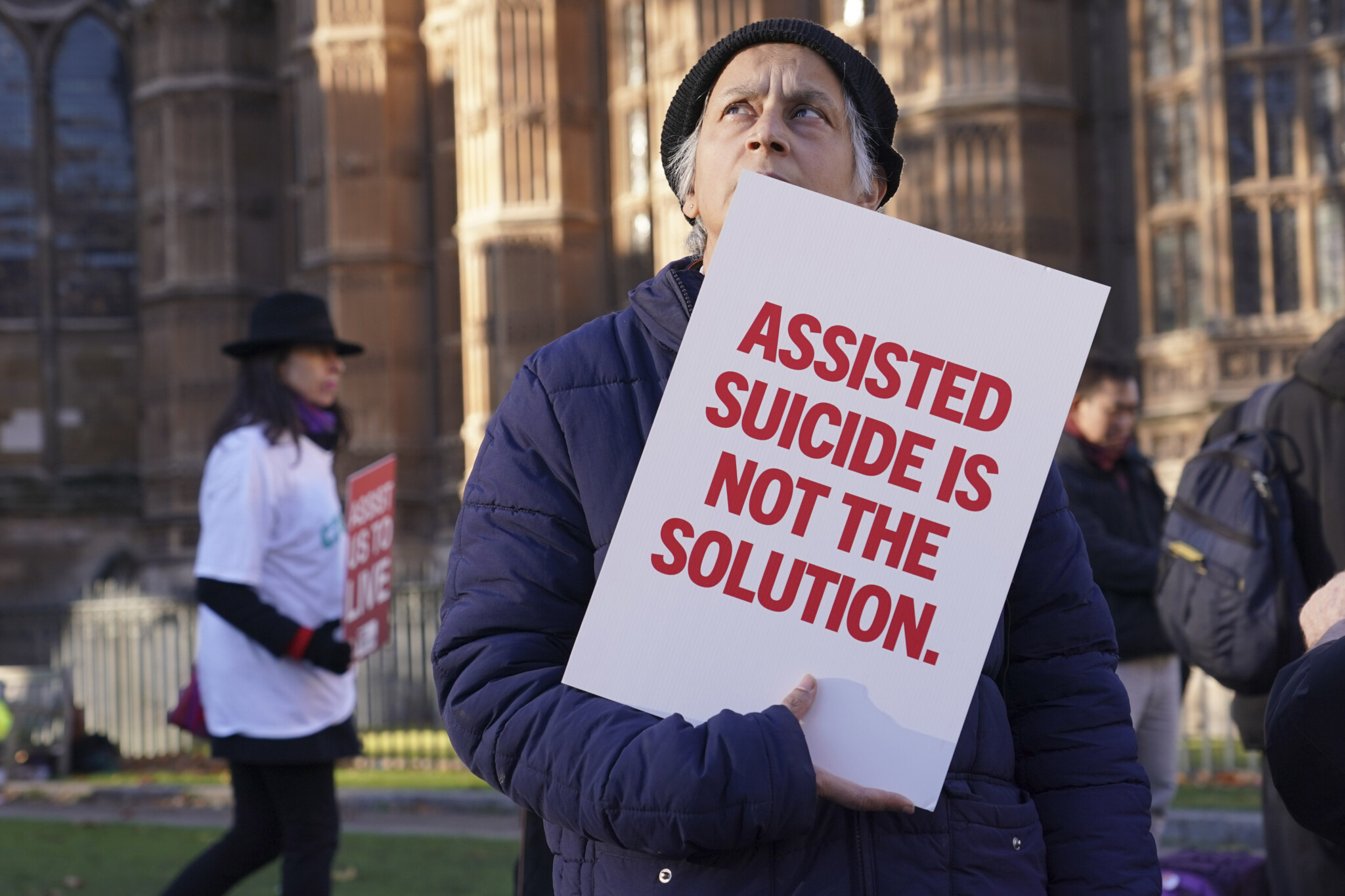

Protesters show placards in front of Parliament in London, Friday, Nov. 29, 2024 as British lawmakers have given initial approval to a bill that would help terminally ill adults to end their lives in England and Wales. Alberto Pezzali/AP Photo.

For Canadians, perhaps the most striking feature of the U.K.’s debate on assisted suicide is how often our country is brought up as an example of how a seemingly compassionate assisted suicide regime can become a nightmare. Our euphemistically named “Medical Assistance in Dying” (MAID) program has made us a global pariah, with the international press reporting on cases of tacit or explicit coercion, slippery slopes, and a failure on the part of MAID doctors to even follow the law.

“Why is Canada euthanising the poor?” asked Canadian expat and Leiden University professor Yuan Yi Zhu in The Spectator’s most-read article of 2022, drawing the world’s attention to the way MAID is playing out in practice, and warning against its introduction in Britain. Even defences of the Leadbeater bill are critical of the Canadian system: “Here’s why the UK won’t end up like Canada when it comes to assisted dying” was published in The Express last week. If assisted suicide eventually fails in the U.K., British politicians becoming spooked by the Canadian example will be a big part of the reason why.

Our status as the global example of how not to legalize assisted suicide is no accident. Unlike the British, who are engaged in a robust public debate and addressing the issue through a democratic process, our MAID program was largely created by the courts. This has resulted in maximalist laws, weak safeguards, and a system that’s expanded rapidly without much democratic review or public input.

The Supreme Court of Canada, in a reversal of the precedent it set in the 1993 Rodriguez case, forced Parliament to legalize assisted suicide only a few years after MPs had overwhelmingly voted not to. The court’s 2015 ruling in Carter laid the foundation for the Liberal government’s MAID bill, C-14, which initially limited assisted suicide to those whose natural death was reasonably foreseeable.

But the courts weren’t done yet. In the 2019 Truchon case, a judge on the Quebec Superior Court ruled that assisted suicide should also be offered to those with chronic conditions but not nearing natural death. This now includes assisted suicide for those with common disabilities like blindness and hearing loss, as well as those suffering from mental health problems like anxiety and depression—conditions that had previously been met with suicide prevention efforts.

Our judicialized approach to a matter of significant public concern both reflects and contributes to weakened democratic institutions. Most of Canada’s elected leaders lack the courage to have thoughtful discussions on serious moral issues, so they defer to the courts, which are happy to enact judges’ progressive policy preferences, precedent be damned. In contrast, British elected officials are having a difficult, grown-up debate, one that will hopefully lead to better policies and more safeguards for vulnerable Britons, while their Supreme Court has agreed (for now) to stay out of it.

Luckily, we in Canada have a solution ready to hand: the notwithstanding clause, which allows our Parliament to reassert its right to make decisions on behalf of the public, even on Charter issues. This clause was included in our Constitution precisely to guard against situations like the one we’re in: where the courts have ordered the design of unworkable systems that are failing people in need, so much so that we’re the rest of the world’s cautionary tale. In the next Parliament, the new government should use the notwithstanding clause to set aside the rulings in Carter and Truchon and establish real safeguards that protect vulnerable Canadians.

Elected leaders can take courage in the recognition that our cousins in Britain have been less enthusiastic about assisted suicide than we might have expected, likely because of the vigorous public debate on the issue. In a recent poll, 70 percent of Britons said they wanted a Royal Commission on end-of-life care before moving ahead with any proposal to legalize assisted suicide. Similarly, the hardened base of support for it was remarkably small: once respondents were presented with ten basic arguments against it, including some drawing on the Canadian example, support for assisted suicide dropped to only 11 percent. This suggests that there is a great deal of fluidity in public opinion on this issue and that a decision to have a real democratic debate on it might be welcomed.

Our democratic institutions aren’t perfect, and no public debate goes exactly as one side or the other might want, but Canadians deserve better than to be governed by the unelected, unaccountable courts on matters of life and death. We deserve elected leaders who seek to lead, not ones who cower from tough decisions or refuse to protect the vulnerable. As the British are showing us, parliamentary democracy and an open, liberal society are much better placed to address these sensitive issues than simply leaving the hardest, most important questions to the nine justices of our Supreme Court.