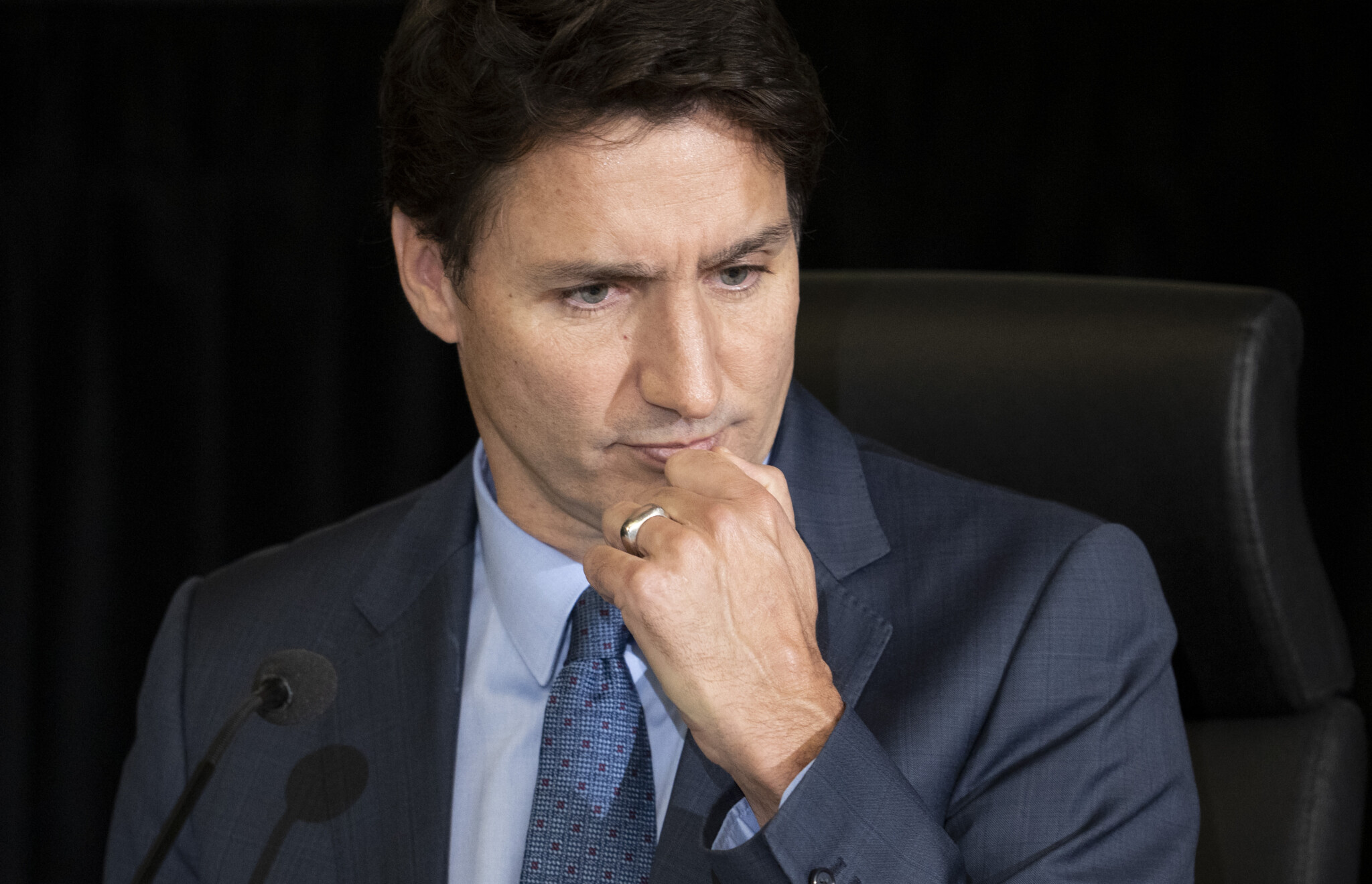

Justin Trudeau is what he is. He is not a lawyer, nor a scholar, nor even a policy wonk. In both nature and nurture, he is merely a politician.

Accordingly, in taking stock of his legal legacy as he prepares to step down as prime minister, one will not find any consistent legal principle or constitutional theory threaded through his government’s legislative record. Instead, you’ll find a mishmash of vague social justice ideologies, people-pleasing, and political necessity.

Trudeau’s government kicked off with a defensible law epitomizing his early “sunny ways” era: a time when his political persona retained its dynamic, progressive, and compassionate aura. This was the Cannabis Act that legalized marijuana for recreational use. It’s true that there have been significant negative externalities from legalization—the ubiquitous smell of burnt marijuana on city streets and in parks frequented by children being a major one—but the Cannabis Act was on the whole a net positive.

There had been a tacit compromise between law enforcement and pot smokers for decades, with law enforcement largely turning a blind eye to personal use and possession, so having laws on the books that criminalized an act that was rarely and arbitrarily unenforced was harmful to the rule of law.

Despite that and other early successes, Trudeau’s social justice instincts led him into absurdities. Most notable was his full acceptance that Canada had committed “genocide” against Indigenous Peoples following the novel definition of the term presented in the final report of 2019’s National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

Trudeau’s government policy was also often marked by hostility towards provincial jurisdiction. The Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act (GGPPA)—the act that imposed carbon taxes on provinces that didn’t have sufficient greenhouse gas mitigation programs in place—made unprecedented forays into provincial sovereignty over property and civil rights. A number of appellate judges in Ontario, Saskatchewan, and Alberta found serious problems with justifying the GGPPA on the basis of the Peace, Order, and Good Government power, but a 6-3 Supreme Court ultimately upheld it.

The carbon tax badly inflamed provincial tensions. Quebec, ordinarily known for progressive climate change policies, joined a number of other provinces to challenge the federal law out of concern for constitutional principle. Later carve-outs to shore up votes in the Maritime provinces showed that the policy had more to do with posturing and politics than uniform national standards.

If the GGPPA inflamed tensions, 2019’s shockingly hubristic Impact Assessment Act (IAA) of 2019, nicknamed the “No More Pipelines Bill,” led to an all-out crisis of provincial-federal relations. It purported to allow federal oversight of all major infrastructure projects, including dams, mines, and pipelines. If it wanted to, the federal government would declare the project as controlled by the act and threatened huge fines if it proceeded before they had considered the project’s impacts on health, gender, and Indigenous Peoples. The federal government had essentially assigned itself a veto power over any project. A 5-2 majority of the Supreme Court rejected the blatant power grab, finding that the bill was aimed at regulating projects that often fell squarely within provincial jurisdiction.

Supporters gather near the legislature to protest during a demonstration against COVID-19 restrictions in Victoria, Feb. 5, 2022. Chad Hipolito/The Canadian Press.

Beginning in 2021, Trudeau took aim at online platforms, news, and speech. The Online Streaming Act, which became law in 2023, regulates pretty much the entire internet. It mandates YouTube, TikTok, and other video- and audio-sharing sites to feature, through a state-skewed algorithm that mandates enhanced “discoverability,” more Canadian content. As to what counts as “Canadian content” is as-yet undefined, giving government bureaucrats ample discretion to filter out content made by Canadians that doesn’t carry a desirable ideological posture and prioritize content that does.

The Online News Act, also passed in 2023, requires that Google and Meta compensate news sites for linking to their content. As The Hub has well documented, it is essentially a subsidy for legacy media.Digital media expert Michael Geist called the act “an utter disaster, leading to millions in lost revenues with cancelled deals, reduced traffic for Canadian media sites, declining investment in media in Canada, and few options to salvage this mess.”

Any overview of Trudeau’s governing legacy is woefully incomplete without a major focus on what happened in 2022 when big rigs, bouncy castles, and Canadians who were demoralized during a long, brutal pandemic took up residence on Parliament Hill. Trudeau, after sequestering himself at his Harrington Lake cottage in horror, announced on February 14 that his government would be the first to invoke the Emergencies Act.

Just under two years later, a judge of the Federal Court found that the invocation was unlawful, that the statutory requirement of a public order emergency posing a threat to the security of Canada was unmet, and that there was no “national” emergency. The judge also found that the measures taken by the government pursuant to the act, most famously freezing bank accounts of those involved with the convoy, violated Charter rights unjustifiably.

Much ink has been spilled about Trudeau’s invocation of the act.Including its eerie parallel with his father’s invocation of the War Measures Act during the FLQ crisis, how it punctuated his multi-year-long campaign to humiliate and demonize Canadians who were already knocked down by this country’s unending cycle of economically crushing lockdowns and demeaning vaccine mandates, and its evasion of the requirement to meaningfully consult with provincial premiers. But to my mind, what sticks out the most about the whole affair was Trudeau’s extraordinary appearance during the Public Order Emergency Commission, chaired by Justice Paul Rouleau. Trudeau testified in that clammy room with carefully prepared lines, ready to discuss the Emergencies Act down to pinpoint references.

In particular, Trudeau was eager but unable to present his government’s emergent legal theory that the phrase “threats to the security of Canada” in the act does not mean the same thing as “threats to the security of Canada” in the Canadian Security Intelligence Services (CSIS) Act, despite the Emergencies Act itself stating that the meanings in the two are the same. It was a surreal moment of doublespeak, clearly aiming at subverting a legal hurdle that was put in the drafting of the bill for the precise purpose of preventing the type of abuse in question.

The testimony was extraordinary because the Justin Trudeau presenting it was an entirely different creature than the colourful sock-wearing, Bohemian Rhapsody-belting, Indian wedding attire-dancing feminist image he’d built his long and successful political career upon. This Justin Trudeau turned up in a more familiar political archetype: asserting power and twisting language to defend the exercise of power and disregard for rights. Power, in the normal coercive sense, to the effect of deploying police horses to corral demonstrators and locking families out of bank accounts for supporting causes he disagreed with.

In the end, Trudeau’s “sunny ways” devolved into a peculiar form of Canadian authoritarianism—one that weaponized emergency powers to suppress dissent and lied about it afterward. That should be the lasting image of Trudeau’s legacy—legal or otherwise.