Welcome to Need to Know, The Hub’s roundup of experts and insiders providing insights into the developments Canadians need to be keeping an eye on.

Today’s edition touches on the most important economics stories capturing headlines this week, including Donald Trump’s inauguration, the trade tariffs that weren’t, and why the rest of Canada outside of Alberta should care about oil and gas too.

The threat of chaos remains

Theo Argitis, managing director at Compass Rose Group and publisher of the Means & Ways newsletter

Donald Trump’s inauguration on Monday brought a fleeting sigh of relief for Canada following reports that we might avoid an immediate trade war with the U.S.—a conflict that could plunge our economy into recession and fuel fresh inflationary pressures.

Early in the day, multiple news organizations reported that instead of imposing tariffs, Trump planned to direct U.S. federal agencies to scrutinize trade practices involving Canada, Mexico, and China. The Canadian dollar rallied on the news. Yet, by evening, as Trump signed executive orders in the Oval Office, he told reporters he was still considering a 25 percent tariff on Canadian and Mexican goods starting February 1.

The threat of chaos remains, leaving Canada on edge.

Let’s hope those remarks were merely more bluster. For Canada, a cooling-off period would represent the best-case scenario, buying critical time for both our economy and policymakers.

First, it allows the Canadian economy more breathing room to recover from its recent slump, as the effects of lower borrowing costs begin to take hold. On Monday, the Bank of Canada released survey data that underscored how the improving macroeconomic environment is starting to positively influence business and consumer confidence. While sentiment remains “subdued,” businesses are increasingly optimistic about their sales potential and investment outlook. Consumers, too, are reporting improved financial health and sentiment.

This recovery is poised to gain momentum as the Bank of Canada continues its rate-cutting trajectory, with another reduction likely on the horizon next week.

Second, Canadian policymakers need more time to craft a sophisticated and coherent strategy to address Trump’s trade concerns and avoid a damaging trade war. The Canadian government has signaled its readiness to retaliate against any U.S. tariffs with countermeasures designed to impact the American economy. While this posture may make sense as a negotiating tactic, it is unlikely to be credible in practice.

Canada’s economic reliance on U.S. exports far outweighs the reliance the U.S. has on Canada. In such an uneven fight, retaliatory tariffs would likely hurt Canada more than they would harm the U.S. To prevail in this scenario, Canada would need extraordinary national resolve—a level of unity that is far from guaranteed.

Trump’s fundamental economic goal is to shift consumption toward U.S.-produced goods and services. For Canada, the challenge is clear: we must develop a strategy to align with this objective while protecting our economic interests.

Editor’s note: This post has been updated to reflect further reports.

The federal fiscal footprint is on the rise

By Livio Di Matteo, a professor of economics at Lakehead University

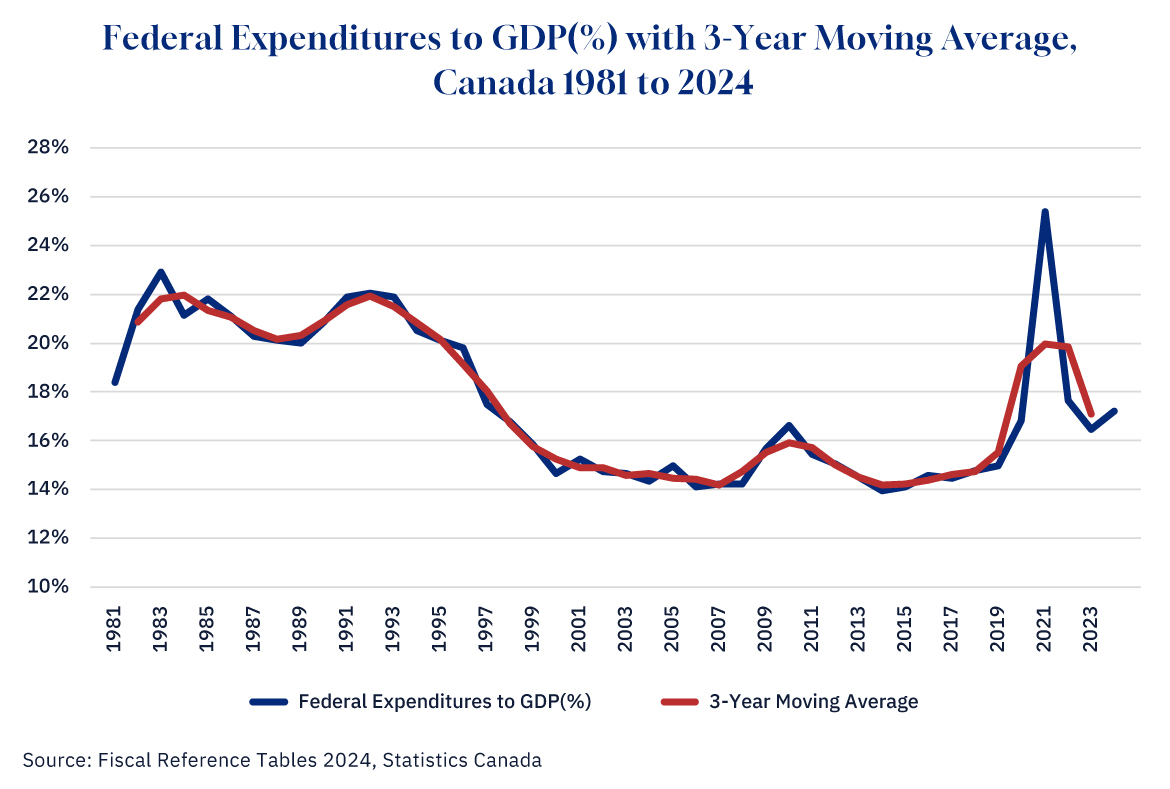

Since 1981, there have been four phases to the total federal expenditure to GDP ratio or what can be termed the federal fiscal footprint. For much of the 1980s, the size of the federal public sector averaged about 21 percent. The 1990s and the federal fiscal crisis saw budgetary measures taken that came with a decline in the federal fiscal footprint with a drop from 21 percent in 1990 to 16 percent by 1999.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

The period afterwards stretching from 2000 to 2015 was one of relative stability (aside from the upsurge of the 2008-09 financial crisis and recession) and the federal fiscal footprint during this third phase averaged 15 percent with lows of 14 percent reached. Since 2015, the trend has been upwards even if one chooses to omit the pandemic and simply look at endpoints. In 2015, the federal expenditure to GDP ratio stood at 14 percent and by 2024 it was at 17 percent. The size of the federal public sector as a share of GDP is now where it was in the late 1990s.

The rest of Canada should care about oil and gas too

By Trevor Tombe, professor of economics at the University of Calgary and a research fellow at The School of Public Policy

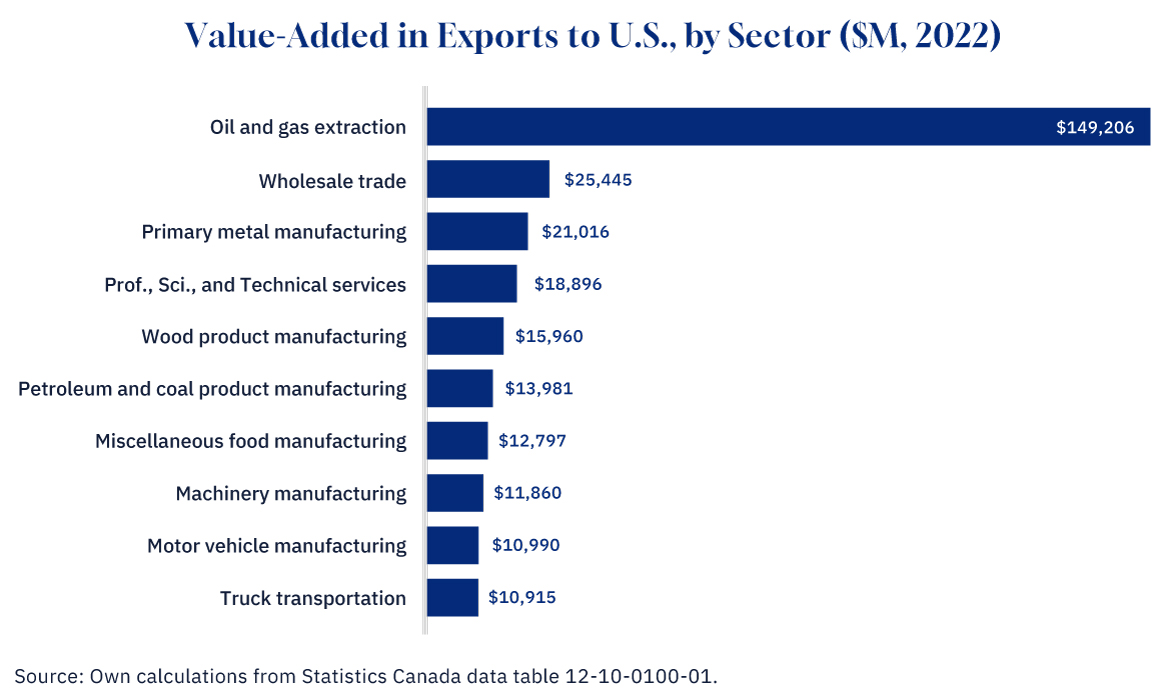

When Canadians outside Alberta think of major industries, they often picture auto manufacturing before oil and gas. The simple reality is that oil and gas bring in far more income and support far more employment than any other sector.

According to the most recent data from Statistics Canada, Canadian workers and business owners earned nearly $150 billion in income from oil and gas exports to the U.S. in 2022, dwarfing other sectors. By contrast, income from motor vehicle manufacturing exports accounted for $11 billion (add in parts, bodies, and trailers and you roughly double this).

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

While exports of motor vehicles to the U.S. are higher than this ($35 billion), much of the revenue is offset by the heavy use of imported intermediate inputs by the sector, many of which originate in the U.S. itself. This means the actual income earned by Canadians from this sector is far lower than commonly assumed.

It’s not just about the income generated from exports to the United States that matters; the potential impacts on jobs are also important. And even by this measure, oil and gas leads the pack. The number of Canadian jobs embodied within oil and gas exports to the U.S. accounted for over 228,000 jobs in Canada. And fully 40 percent of those jobs are outside Alberta.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

By comparison, the next-largest sectors—professional, scientific, and technical services, and wholesale trade—each supported just over 170,000 jobs tied to U.S. exports. Meanwhile, motor vehicle manufacturing exports to the U.S. accounted for approximately 84,000 jobs, or about one-third of the total from oil and gas extraction.

Blocking oil and gas exports in the event of American tariffs therefore makes even less economic sense than retaliating against the United States by restricting auto exports—which would itself be a foolish decision, and luckily not one anyone has seriously suggested.

Five reasons Canada-U.S. trade tariffs are a terrible idea

By Douglas Porter, chief economist at BMO Economics.

Below, are five reasons why singling out Canada for trade tariffs would be an ill-advised move by President Trump.

1. The U.S. would be inflicting harm on its biggest single export market in Canada, with Mexico ranking as the number three export market. Combined, these two economies have absorbed $683 billion of U.S. goods exports over the past year, or roughly 2.3 percent of GDP.

2. Trade with Canada is much more evenly balanced than with other major economies. The ratio of U.S. exports to imports of goods with Canada was 85 percent in the past 12 months, compared with a global ratio of 64 percent. If we include services, the ratio with Canada rises to 92 percent.

3. The deficit with Canada accounts for barely 5 percent of the overall U.S. gap. The deficit on goods and services with Canada accounts for just 0.1 percent of U.S. GDP.

4. The U.S. runs a large services surplus with Canada, which, if anything, is likely understated. Flows from tourism, licensing fees, professional services, and digital subscriptions were in a net $35 billion USD surplus for the U.S. over the past four quarters (to Q3).

5. Tariffs on Canada and Mexico will likely just prompt trade and import diversion to other economies. Tariffs on autos from its USMCA partners could simply prompt a flood of imports from Korea, Japan, Europe, and possibly China. While one ultimate goal of said tariffs is to relocate vehicle production stateside, it could backfire by simply quickening production to lower-cost jurisdictions.

This edited excerpt was originally published at BMO.