While tariff threats are being thrown out like candy at a parade, it’s worth remembering that the laws of economics are not in President Trump’s favour. And that’s especially true when it comes to tariffs across North America.

Why? Because the North American market is extremely integrated.

Many American (and Canadian) businesses have interdependent facilities that operate on both sides of the border. Countries don’t specialize in the production of a single finished product but rather in a part of the production process: smelting aluminum in one country to be manufactured into an engine in another and assembled with parts from elsewhere, for instance.

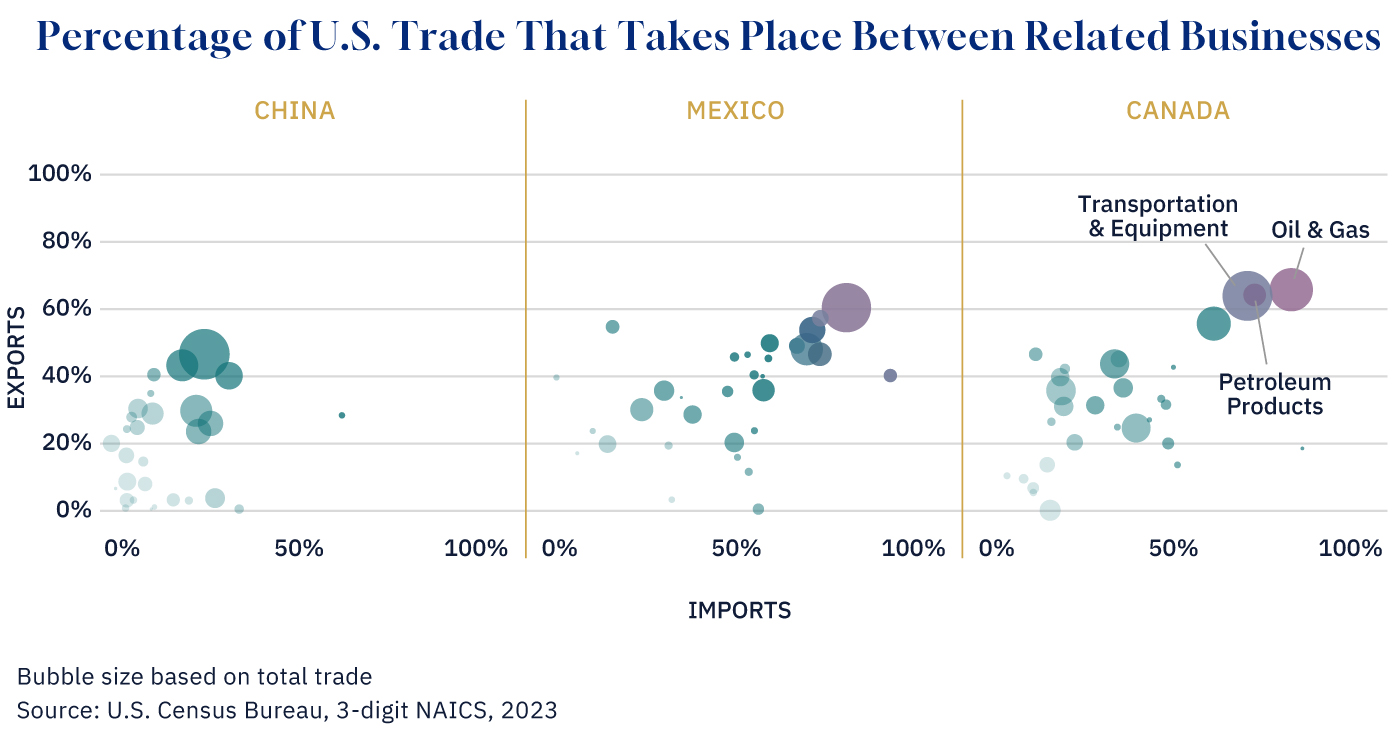

This checks out based on the data. The U.S. Census Bureau divides trade into cross-border purchases made by distinct entities versus those made by related parties. A related party is basically a parent company or subsidiary like Kraft Heinz Canada and Kraft Heinz.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Incredibly, over 50 percent of what the U.S. imports from Canada is purchased by a related company, as is over 60 percent of its imports from Mexico. This means that more than half of the purchases subject to the proposed tariff on Mexico and Canada would fall on American companies “trading” with themselves, increasing their cost of production and decreasing their competitiveness beyond North America.

Likewise, the industries with the highest trade value across North America also have the most intra-firm trade. The oil and gas and automotive industry are great examples. More than 80 percent of oil and gas imports from Canada are purchased by related parties in the U.S. Likewise, over 70 percent of transportation and equipment imports (which would include the automotive industry) from both Canada and Mexico are purchased by related U.S. companies.

The level of integration in North America is especially stark when compared to other markets. Ties between the U.S. and China are not nearly as strong. Most Chinese imports are purchased by individual consumers—think online shopping on Shein, Temu, and the like—or American retailers like Walmart looking to stock their shelves.

All this is to say that uncoupling North America might be messier than President Trump thinks. Even if his long-term goal is to bring back full supply chains to the U.S., their current level of integration means the process of getting there will be costly and cumbersome for U.S. producers and consumers alike.

A version of this post was originally published by the Business Council of Alberta at businesscouncilab.com.