DeepDives is a bi-weekly essay series exploring key issues related to the economy. The goal of the series is to provide Hub readers with original analysis of the economic trends and ideas that are shaping this high-stakes moment for Canadian productivity, prosperity, and economic well-being. The series features the writing of leading academics, area experts, and policy practitioners. The DeepDives series is made possible thanks to the ongoing support of Centre for Civic Engagement.

Ottawa’s deficit is projected to be just under $50 billion this year. According to the latest projections, it’s set to remain above $20 billion until at least 2030.

The risk is undoubtedly to the downside. The uncertainty caused by the threat of U.S. tariffs and now the fallout from their imposition will lower the GDP projections underpinning the government’s fiscal plan. It’s quite likely therefore that the deficit will be higher—particularly this year and next year.

Both Mark Carney and Pierre Poilievre have notionally committed to balancing the budget over the medium term. (Carney’s proposal is a bit complicated: he would separate the government’s operating and capital budgets and balance the former within three years.)

Both have also made significant spending and tax cut pledges that would ostensibly have to be accounted for in their balance budget plans. This means that they’ll actually need to produce an even larger surplus to cover the costs of their policy proposals and still achieve budgetary balance.

The purpose of this DeepDive essay is to set out considerations on how best to do that. It analyses the fiscal policy context and presents thinking on how to control and reduce federal spending in order to free up fiscal resources for new government priorities and ultimately improve Ottawa’s overall public finances.

The key to meeting Carney’s or Poilievre’s ambitious fiscal targets will be a systematic approach to both reviewing existing spending and controlling future spending. As discussed below, such an approach must target ineffective program spending as well as inefficient government operations. The goal should be to reconceptualize both what the government does and how it does it.

Spending is the source of the problem

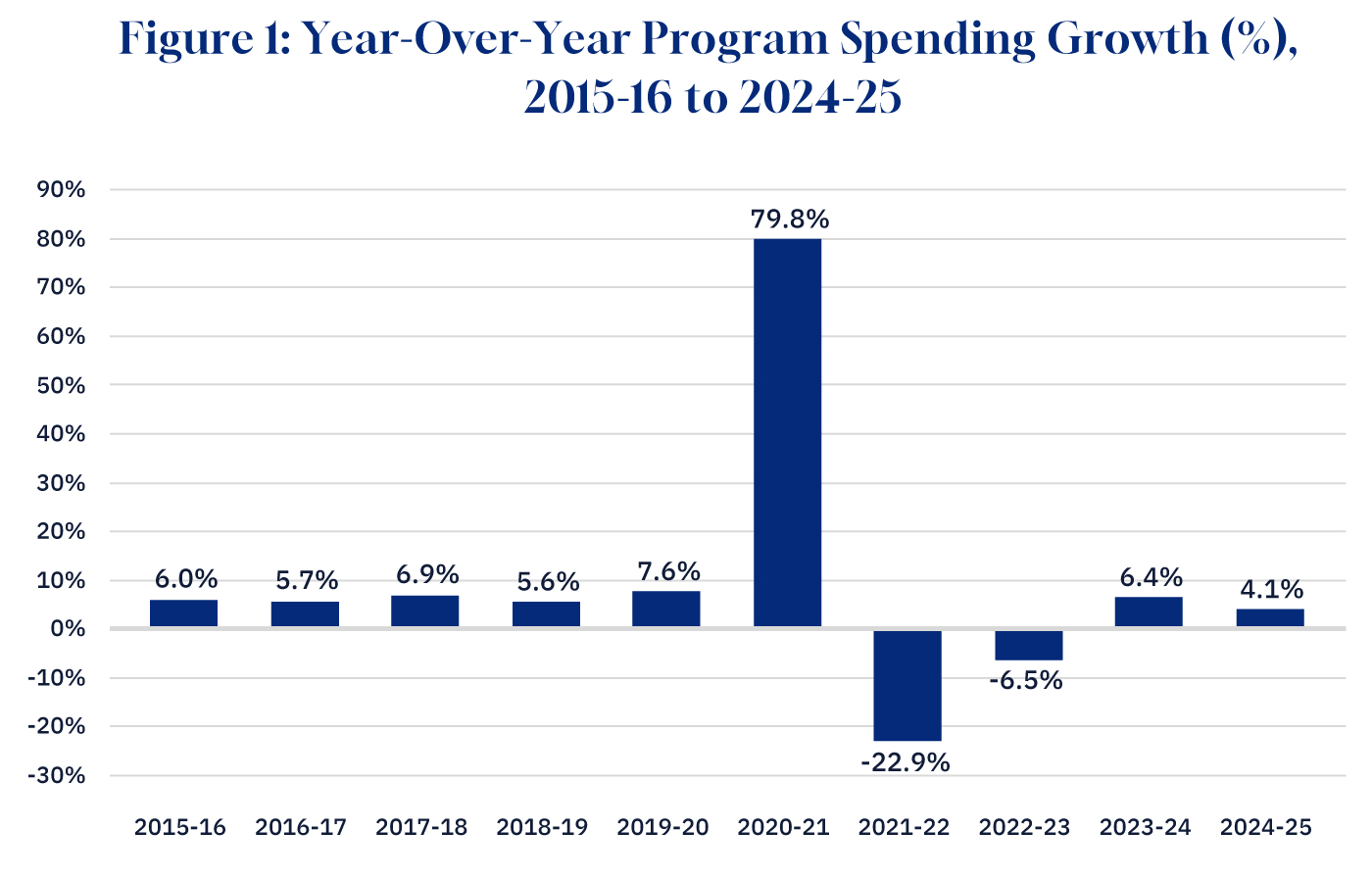

The source of Ottawa’s protracted deficits is its spending growth. This is most evident in the significant rise in annual program spending under the Trudeau government.

By way of background, program spending is the main form of federal operating spending. It consists of transfers to individuals (such as Old Age Security or Employment Insurance), transfers to other orders of government (such as the Canada Health Transfer or Equalization), and direct program spending (such as direct federal programs and basic government operations). The other major operating expense is debt-servicing costs.

Program spending has virtually doubled since 2015-16. Over this ten-year period, average annual growth outside of the extraordinary pandemic years (2020-21 to 2022-23) has exceeded 6 percent (see chart 1). One must go back decades to find a comparable period of such sustained spending growth.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Revenues, by the way, have increased by about 75 percent over the decade and now represent a higher share of GDP than they did when the Trudeau government was first elected. If program spending had increased at a more moderate rate—something more comparable to what we saw in the previous decade by the Harper government—the federal government would have recorded net surpluses instead of massive cumulative deficits over the past 10 years.

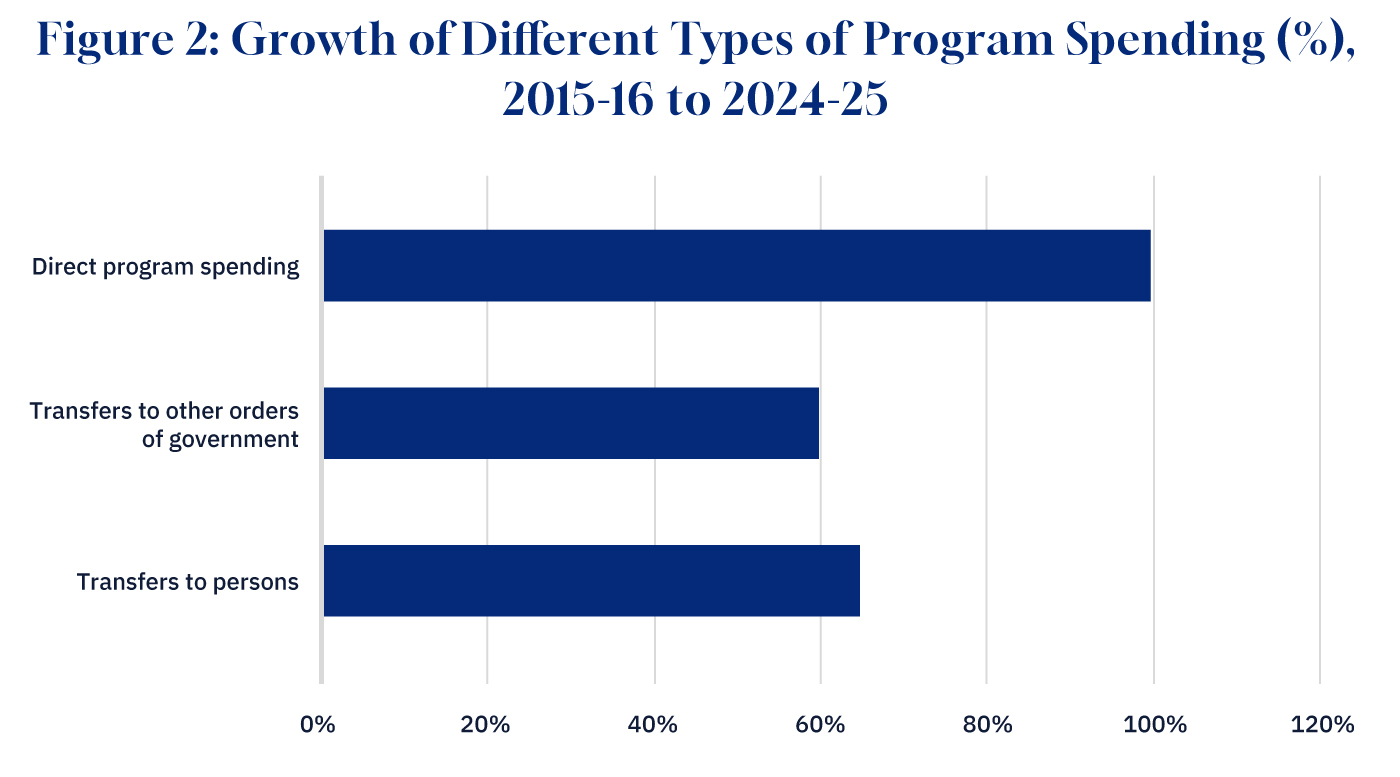

Of this program spending growth, the biggest source of growth has been nominal direct program spending which itself has doubled since 2015-16. Transfers to individuals or other orders of government have grown by 65 percent and 60 percent respectively (see chart 2). (Debt-servicing costs have risen by about 146 percent—from $21.8 billion in 2015-16 to a projected $53.7 billion this year.)

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

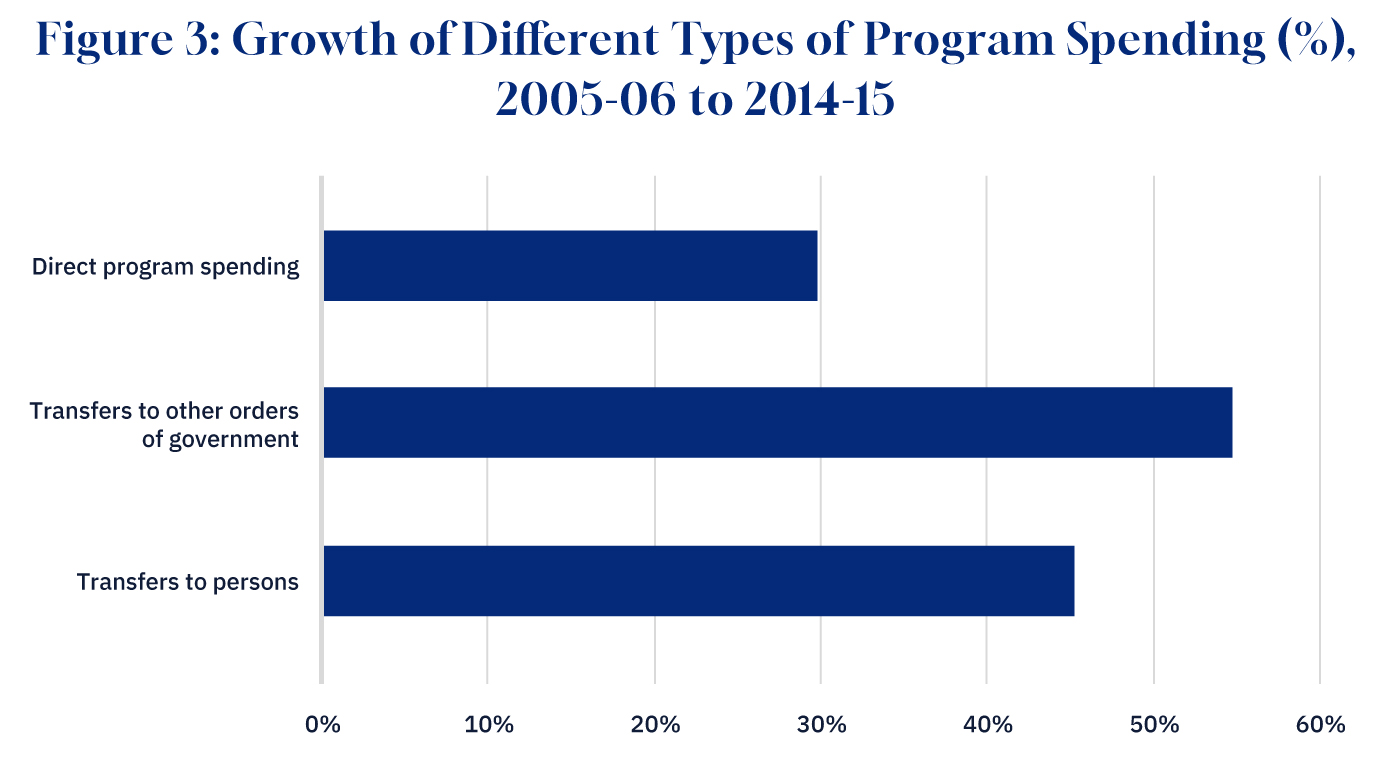

To put this in perspective: during the previous decade under the Harper government, direct program spending (30 percent) grew barely half as fast as transfer payments to individuals and other orders of government (see chart 3). Total program spending increased by 40 percent—or less than half of the growth under the Trudeau government.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

The net effect of this compositional growth of federal program spending is that over the past decade, direct program spending has increased from 5.5 percent of GDP to 8 percent and 38 percent of total federal expenditures to now more than 45 percent.

Both figures represent meaningful increases relative to the norm for the past 40 years or so. Direct program spending is now at its highest percentage of GDP since 1987-88 and the highest share of federal expenditures since 1982-83.

The composition of spending growth matters because it influences the potential sources of fiscal savings—particularly since both Carney and Poilievre had indicated that they’d protect transfer payments from spending cuts. This means that the vast majority of savings will need to come from direct program spending.

The good news is that there’s ostensible room for such savings: direct program spending has grown from $109.2 billion in the final full year of the Harper government to $230 billion this year. Presumably there’s scope to bring direct program spending back to something like the Harper-era levels as a share of GDP. Even lowering it to 7 percent of GDP would represent roughly $30 billion in annual savings relative to the status quo.

The Trudeau-era growth in direct program spending has been driven by different factors. A major one is the expansion of the federal public service itself. The number of federal employees has grown from 257,318 in 2014-15 to nearly 440,000 last year—an increase of more than 70 percent.

The growth in Ottawa’s employment footprint has coincided with a drop in public sector productivity. Estimates by Statistics Canada find that as of 2023, labour productivity within the public sector was stuck at 2015 levels.

The upshot: if the next government wants to balance the federal budget—including accounting for significant new tax and spending measures—and it intends to limit any spending reductions to direct program spending, the large-scale spending growth that we’ve witnessed over the past decade lends itself to rationalization. This incremental spending isn’t mostly going to individuals or other orders of government. It’s an expansion of discretionary program spending (including government operations) that should be subjected to a dual lens of efficiency and effectiveness. A 70-percent increase in federal employees alone calls out for a systematic review.

Ottawa needs an operational and programmatic review

It’s been 30 years since the Chretien government announced the sweeping results of its Program Review. It was a major spending review that rationalized program spending, including transfer payments and direct program spending. The net effect was to reduce overall program spending by roughly $9 billion per year.

Program Review was principally motivated by cutting costs and reducing the federal deficit. Issues like government efficiency or public sector productivity were secondary to the overriding deficit reduction goal. As a result, the major cost savings came from statutory programs (such as Employment Insurance) and reducing intergovernmental transfers (such as the Canada Health and Social Transfer). Reductions to public sector employment which ultimately totaled about 45,000 (or 19 percent) were mainly due to these programmatic cuts.

In 2011, the Harper government carried out a broadly similar exercise. Its Deficit Reduction Action Plan excluded transfer payments and instead sought to achieve roughly $5 billion in annual savings from direct program spending alone. The exercise was successful in that it ultimately met its savings target, including roughly 20,000 job cuts over three years. But it, too, relied heavily on programmatic cuts and set aside questions concerning government operations. The exceptions were the modernization of the pay system and consolidation of federal emails—both of which proved to be costly and unsuccessful.

This brief history is important because it demonstrates that although the federal government has been successful in the past at carrying out major spending reviews, these exercises have tended to be overindexed for program cuts and underindexed for operational improvements. Put differently: successive governments have led spending review exercises that didn’t really scrutinize the government itself.

As Carleton University professor Jennifer Robson has written of Program Review: “It didn’t start from the premise that government just needed to be more productive and do more with less.”

Cranes surround the Peace Tower on Parliament Hill in Ottawa as construction on centre block continues, Friday, Jan.24, 2025. Adrian Wyld/The Canadian Press.

While doing more with less shouldn’t be the totality of a federal spending review, it seems like a missed opportunity not to ask whether there’s scope to boost public sector productivity or adopt better means to deliver core government functions. There’s also a fairness dynamic at play. It seems inherently unfair to Canadian taxpayers if billions of dollars of spending cuts—especially the magnitude contemplated by Carney and Poilievre—only come from public-facing programs and services and government operations are somehow off limits. Looking ahead, the federal government should subject itself to both an operational and programmatic review.

The programmatic side of the equation is straightforward: Ottawa should draw on the best practices from Program Review and the Deficit Reduction Action Plan to eliminate or reform ineffective programs. There’s of course room for adjustments and improvements to these previous exercises, including for instance expanding the review base to cover tax expenditures.

But overall the goal is to shift scarce public dollars from low-performing or low-priority programs to higher-priority and better-performing ones. A simple way to think about it as an exercise in determining what the government should do.

The operational part is far less normative. It’s not so much concerned with what the government ought to do as it is about how the government does it. It’s mostly a technocratic question. After a 70-percent increase in federal employment, it seems quite reasonable to scrutinize government efficiency in the name of improving fiscal outcomes, including the potential to streamline internal rules and red tape to eliminate redundancies or to make greater use of technology in program or service delivery.

The Trump administration’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) exercise may offer some useful lessons in this regard. This, it must be said, isn’t a full endorsement of the process or some of its particularities. Robson and others have highlighted some legitimate problems with it. But DOGE’s focus on improving government operations distinguishes it from Canada’s past rounds of spending review in ways that can be instructive for Canadian policymakers.

The executive order that established DOGE in January sets out as its primary goal to “modernizing Federal technology and software to maximize governmental efficiency and productivity.” Thus far this has manifested itself in a series of initiatives with respect to workforce optimization, office space utilization, software modernization, and leveraging productivity-enhancing technology.

It’s too early to assess whether DOGE will boost government productivity and lower its operating costs but there are signs that it’s identifying valuable areas for operational efficiencies. Take software licenses for instance. DOGE staff are auditing software licenses across departments and agencies and discovering that many are paying license fees that far exceed their number of employees. As a result, the General Services Administration has recently deleted nearly 115,000 unused software licenses and 15 underutilized or redundant software products.

These types of initiatives are consistent with similar cost-cutting approaches that one finds in the private sector. Companies are always searching for options to boost their productivity and in turn their profitability. Although governments don’t have the same profit motives, higher productivity can enable them to stretch public dollars further and therefore preserve key programs and avoid tax increases.

Elon Musk’s involvement in the process is a recognition that entrepreneurs and technologists have unique experience with rationalizing operational spending and boosting internal productivity. They certainly have more practical expertise in these matters than the management consulting firms with whom the government typically contracts, including as much as $220 million in 2024 for the “Big Four” consulting firms—Deloitte, PricewaterhouseCoopers, KPMG, and Ernst & Young—alone.

The key point here is that, given both Carney and Poilievre have implicitly committed to bigger spending reductions than we saw in the 1990s or 2012, it seems wrong and impractical to exclude government operations from scrutiny. Challenging the system to be “more productive and do more with less” seems not only wholly appropriate but, in light of the current scale of budgetary demands, necessary to managing fiscal scarcity.

It should also be noted that although Robson is of course right that it’s not necessarily the case that pre-2015 government operations and program spending were the “high water mark,” it’s also true that it’s not obvious that the current size and scope of the federal government is optimal either. If anything, the departure from 40-year norms on the size and share of direct program spending ostensibly puts a greater onus on the system to justify its efficiency and outcomes.

Leveraging Canada’s successful experience with programmatic reviews and incorporating some of the early lessons from DOGE on pursuing operational efficiencies would result in a better process that’s concerned with both what government does and how it does it.

President Donald Trump listens as Elon Musk speaks in the Oval Office at the White House, Tuesday, Feb. 11, 2025, in Washington. Alex Brandon/AP Photo.

Other operational and policy considerations

In addition to launching a comprehensive review of government operations and programmatic spending, there are other steps that the next government should take to review and control federal spending. Here are three.

1. Reverse delegated authorities

The government makes thousands of spending decisions per day. These can include the approval of grants to businesses, municipalities, or non-profit organizations, government contracting, or internal spending. It’s impractical for cabinet ministers to approve such a scale of individual spending decisions so they’re delegated to various levels of government officials, including deputy ministers or other senior public servants, according to their dollar value thresholds.

Although this is sensible from an efficiency standpoint, decentralizing spending approvals can make it challenging to fully understand the scale of program spending, the inherent tradeoffs between different types of spending, or even whether the recipients and their purposes of spending are consistent with the political arm of the government’s agenda.

There isn’t reliable data on the full scale of delegated authorities across the government but there’s reason to believe that it’s significant. It’s notable for instance that the number of decisions that require approval from the Treasury Board cabinet committee has markedly fallen in recent decades. In 1983, the Treasury Board rendered roughly 6,000 decisions. Today it’s about 900. The difference has been pulled into departments and may involve no scrutiny from the political arm of the government at all.

An incoming government should reverse all delegated spending authorities across the government and then gradually rebuild them in an exercise similar to “zero-based budgeting.” Although such a process would create some short-term frictions, it would permit cabinet ministers and their staff to better understand their departments and the programs that they operate. It would also in theory have the effect of offsetting a pro-spending bias within the system. If departments know that spending decisions will be subject to political review, it will ostensibly cause them to sharpen their analysis and forgo marginal or costly proposals.

Over time, the government can restore delegated authorities based on a better understanding of the tradeoffs between efficiency and accountability. Most would agree for instance that a cabinet minister probably doesn’t need to sign off on low-cost office parties. But on major procurement decisions or grant approvals, it probably makes sense for individual ministers or the Treasury Board to reassert themselves.

2. Meritocracy in a unionized work environment

Roughly 70 percent of federal government employees are union members working under collectively bargained arrangements. This imposes some constraints on the government’s ability to prioritize merit when it comes to hiring, compensation, promotion, and workforce adjustment. An incoming government should explore options to grant itself greater scope to prioritize meritocracy within the public service.

For instance, the government should significantly expand the Interchange Program to draw on private sector workers to fill temporary roles in the public service. Not only would this bring new and different voices into the system, but by hiring them outside of collectively bargained arrangements, it would grant the government greater flexibility to hire the best people from across the economy.

Similarly, the government should experiment with different types of public institutions and human resource models. For instance, the current treatment of political staff as “exempt staff,” which refers to their exemption from parts of the Public Service Employment Act, could in theory be extended to other parts of the government, including new institutions designed precisely to sit outside of conventional employee-employer arrangements. This could enable talented people to join the government on short-term, mission-driven projects outside of the centralized process led by the Public Service Commission and Treasury Board Secretariat.

As for tilting more in the direction of performance pay, the government currently has a system for employee evaluations but merit-based pay is more limited—particularly for those outside the senior ranks. There’s a strong case that the government should prioritize performance-based bonuses in future rounds of collective bargaining even if it comes with other tradeoffs. Modernizing the compensation model based on performance rather than automatic step increases is key to elevating and rewarding high performers within the government.

Relatedly, the government should seek greater flexibility in collective bargaining for layoff procedures and displacement. The system still generally preferences seniority-based outcomes rather than according to merit. That needs to change—especially in the context of a major spending review exercise. It would be detrimental to the goal of achieving greater productivity if the government ends up firing a number of high-performing employees due to an archaic focus on tenure rather than merit.

The same priority applies to government executives. For these executives, performance pay can add as much as $15,000 to $50,000 or more to their annual salaries, but it still typically amounts to no more than 10 or 20 percent of total compensation. The government should revisit these limits in order to increase the upside for high-performing executives.

The overall goal of these various types of reforms is to better align hiring, compensation, promotion, and workforce adjustment to merit. Although there may be some inherent constraints to how far the government can push in this direction, one can argue that it’s so important to change the culture and incentives within the government that it would be worth it to compromise on other union priorities in order to achieve it.

3. The role for yearly spending reviews

Although a comprehensive operational and programmatic review as set out above must be a priority, the goal shouldn’t be just to realize short-term fiscal savings. It ought to be to establish a culture of ongoing operational efficiencies and programmatic priority setting.

The Harper government’s strategic review process (which was run from 2007 to 2009) ought to be reinstituted following the major operational and programmatic review. Strategic reviews weren’t motivated by deficit reduction. They were principally focused on controlling or limiting the growth of new spending by reallocating departmental spending from low- to high-priority initiatives.

Under the Strategic Review model, roughly 25 percent of government spending was reviewed annually over a four-year cycle. Participating departments in a given year were identified in the early spring. They were given a spending base and a 5 percent target from the Treasury Board Secretariat and required to conduct a self-evaluation of where they proposed to achieve these savings from low-priority and low-performing programs. Departments were then free to put forward alternative spending proposals to reinvest their savings back into their own budgets.

This type of mechanism is important to control the growth of program spending. It’s not just enough to carry out major spending reviews every decade. That only cuts back on existing spending. It doesn’t affect the growth of new spending. Strategic reviews were generally successful at pushing departments to weigh their new priorities against existing ones and self-finance the creation of new spending programs. In 2007, for instance, the reviews produced about $386 million in gross savings—of which $259 million was reinvested back into the same departments and agencies.

Key takeaways

If Carney and Poilievre’s fiscal commitments are to be taken seriously, they both involve significant reductions in the federal program spending.

Achieving such ambitious fiscal targets will require them to carry out a comprehensive review of federal spending. Previous reviews have tended to focus solely on program spending and by and large ignore government operations. It should be both this time. Direct program spending (including on government operations) has doubled over the past decade, including a 70-percent increase in the federal workforce. There’s scope here to realize operational efficiencies by eliminating redundancies, making greater use of technology, and boosting public sector productivity.

Notwithstanding the controversy around it, the DOGE exercise in the U.S. may offer some useful lessons. One doesn’t have to fully support its particularities to see that its focus on issues like workforce optimization, office space utilization, software modernization, and leveraging productivity-enhancing technology can also apply to the Canadian spending review exercise. Canadian policymakers should draw on the good aspects of DOGE and discard the bad ones.

In addition to these immediate-term steps to reduce federal program spending, there are other ones that the government should take to strengthen a culture of performance and control the growth of new spending.

The ultimate goal of these various measures should be understood as reconceptualizing what government does and how it does it.