DeepDives is a bi-weekly essay series exploring key issues related to the economy. The goal of the series is to provide Hub readers with original analysis of the economic trends and ideas that are shaping this high-stakes moment for Canadian productivity, prosperity, and economic well-being. The series features the writing of leading academics, area experts, and policy practitioners. The DeepDives series is made possible thanks to the ongoing support of the Centre for Civic Engagement.

It was November when the virus first emerged in China. By late February it had arrived in Canada, when a traveler from Hong Kong, an elderly woman, returned home to Toronto, bringing the disease with her. Ten days later she was dead. A week later, so was her son. As the virus began to rapidly spread between health workers and patients, from hospital to hospital and clinic to clinic, public officials were forced to contend with the inevitable: Canada was dealing with its own outbreak of the highly contagious Asian disease that risked spiralling out of control.

Hospitals in the city began closing emergency rooms and intensive care services, and by March 26 the Ontario government declared a provincial state of emergency, ordering all hospitals in the city to activate “Code Orange” plans. Non-essential hospital services were suspended, visitations were ended, and quarantines were enforced.

By the time the “mini pandemic” was over in the summer of 2003, SARS had infected 438 people in the country. Ultimately, 44 Canadians died.

Already by May 2003, Health Canada had established a National Advisory Committee on SARS and Public Health. The federal government, based on recommendations in the committee’s “Learning from SARS” report, established the Public Health Agency of Canada in 2004.

Ontario, for its part, also launched a commission to investigate the crisis, ultimately leading to the formation of its own new public health agency in 2008, Public Health Ontario.

Nearly two decades on from the SARS scare, as the calendar turned to 2020, once again news of a new and unknown virus emerging out of China began filtering through scientific backchannels, paranoid social media posts, and the odd international news report. What began as easily ignored whispers became the unavoidable cacophony of quickly overfilling emergency rooms in Wuhan, Rome, and soon the rest of the world. Three months into the new year, on March 11, 2020, after more than 118,00 cases in 114 countries resulting in 4,291 deaths, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared COVID-19 a worldwide pandemic.

What came next was years of lockdowns, confusion, sickness, death, societal strife, and political polarization.

As we mark the fifth year anniversary of the COVID-19 pandemic, several years since lockdowns ended, and following millions of Canadian cases and tens of thousands of Canadian deaths, we have yet to see any comparable governmental urgency or effort to dispassionately and comprehensively examine the successes and failures of Canada’s pandemic response.

An eagerness to move on from the long COVID-19 years is understandable. But not investigating at the highest governmental level how we got here, what we learned, and how to move forward is irresponsible.

Others have attempted to fill the vacuum, but no royal commission has been struck or national inquiry ordered and no comprehensive federal report has been written. While producing such a report is clearly beyond the scope of this article, the following DeepDive aims to contribute to our understanding of Canada’s pandemic experience and our collective response. In particular, it profiles five key statistics telling five key stories from the COVID-19 pandemic, five years on.

A man squats outside a treatment room as an elderly person receives help with breathing via a manual ventilator pump at the emergency department of the Baoding No. 2 Central Hospital in Zhuozhou city in northern China’s Hebei province, Dec. 21, 2022. AP Photo, File.

27.3 million: An immense loss of life

There’s a video that went viral recently. It’s of a comedian, on stage at a club, setting up a joke about the pandemic. He sets the bait: “Y’all feel like the world is finally back?”

A woman answers, one word: “No.”

Delighted, the comic plays to the rest of the crowd, “There’s always a negative person: ‘It will never be the same!’” before turning back to her: “You said it’s not back—what’s missing?”

One word: “Everything.”

He laughs, “Like what?” before pressing: “Come on, you gotta give me specifics. What is something that you had before COVID and you don’t have it right now?”

Her voice breaks over one more word: “Family.”

“Wait.”

The comic’s sheepish grin turns to an embarrassed smile.

“My fault. I’m sorry for your loss.”

The crowd laughs uncomfortably; he leans into it.

“I forgot that that was the big part of the whole…that was the main issue.”

The crowd keeps laughing, trying to relieve the tension.

“Her family died—stop laughing!”

The comic sighs, takes a big sip of his drink. The video ends.

Worldwide deaths and cases

In terms of how many people were infected by COVID-19, the WHO reports a cumulative total of over 770 million confirmed global cases as of February 2025. Canada has had 4.8 million total cumulative cases, while the U.S. has had over 103 million.

When it comes to calculating or representing pandemic deaths, various forms of measurement exist. Total cumulative deaths are reported deaths caused by probable or confirmed COVID-19 cases. The death rate is the amount of people who died from COVID-19 relative to a given population. The crude mortality (or case fatality) rate measures the risk of dying of COVID-19 if one contracts the disease.

Estimating the exact number of deaths caused by COVID-19 is not a straightforward task given the difficulties in gathering accurate data from every country on earth. For instance, while the WHO only reports 122,398 total cumulative COVID-19 deaths from China, a CDC study estimates that approximately 1.4 million people from China died from the disease between December 2022 and February 2023 alone.

Overall, the WHO reports that 7.1 million people worldwide have died from the disease (as of August 2024).From the WHO: “A COVID-19 death is defined for surveillance purposes as a death resulting from a clinically compatible illness in a probable or confirmed COVID-19 case unless there is a clear alternative cause of death that cannot be related to COVID-19 disease (e.g. trauma). There should be no period of complete recovery between illness and death.”

The United States claims the top spot in total reported cumulative deaths, at 1.2 million. Rounding out the top five are Brazil (702,000), India (534,000), Russia (404,000), and Mexico (335,000).Compared to other epidemics and pandemics, COVID-19 ranks fifth in terms of death toll, behind the 1918 Flu (1918-20; 17-100 million dead), the Plague of Justinian (541-49; 15-100 million dead), HIV/AIDS (1981-present; 44 million dead), and the Black Death (1346-53; 25-50 million). This should not be taken to mean that the U.S. truly led the world in COVID-19 deaths. These rankings, while informative to some extent, are also a function of reporting quality. As outlined above, the actual number of deaths in countries with poorer or less reliable data, such as China, will be underrepresented while countries with more reliable data, such as the U.S., are overrepresented.

In Canada, the WHO reports 55,282 deaths, which represents the 25th-highest number of total reported cumulative COVID-19 deaths in the world.

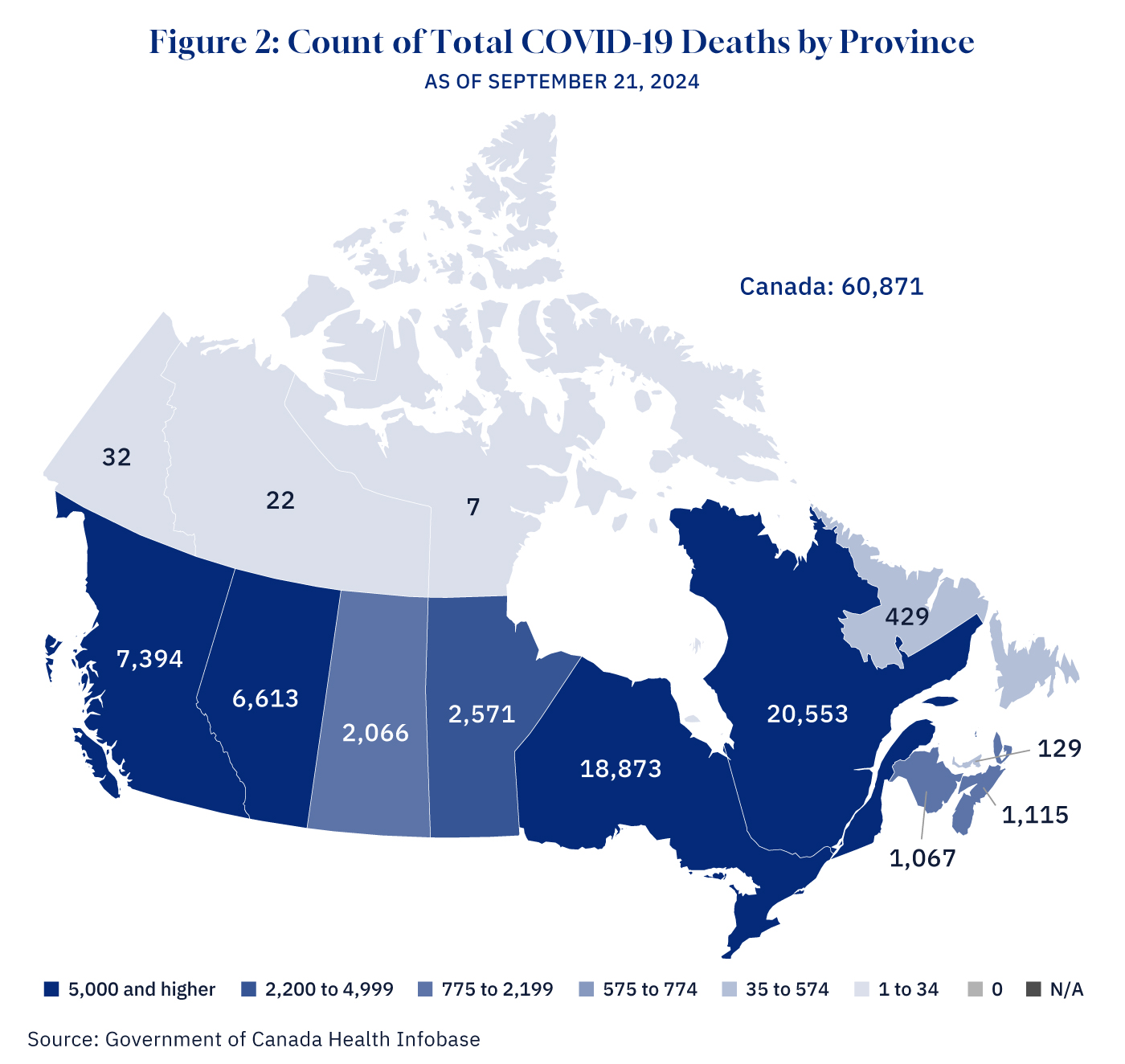

The Canadian government reports slightly higher numbers than the WHO, at 60,871 total deaths (as of September 2024).Elderly Canadians in long-term care facilities were initially hit the hardest. As of December 2021, long-term care residents accounted for 3 percent of cases and represented 43 percent of deaths, according to the Canadian Institute for Health Information.

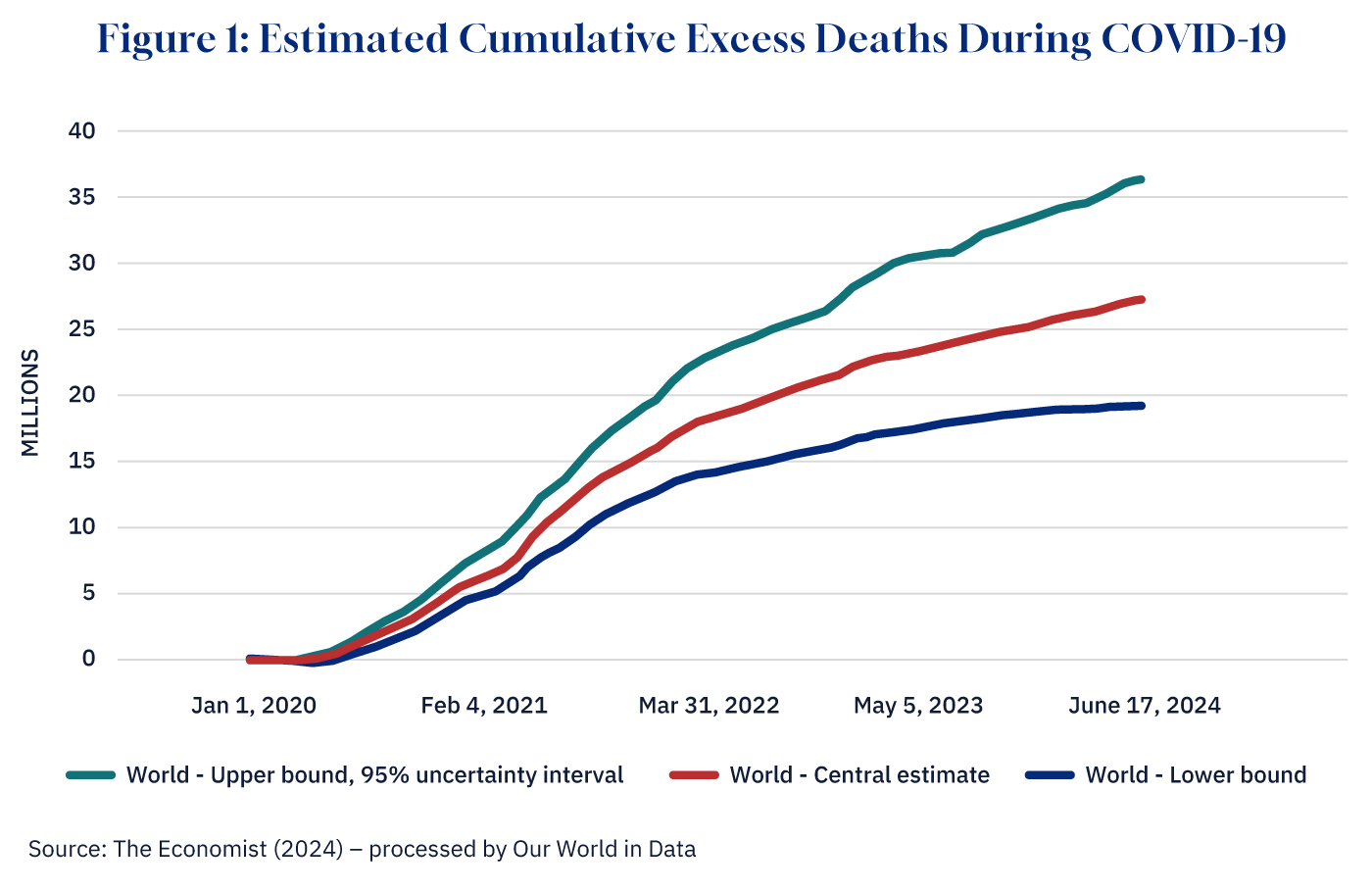

The true number of deaths from the pandemic, however, is estimated to be much higher than the officially reported figures. An AI model developed by The Economist and used to calculate the global estimated excess mortality finds that between 19.2 and 36.3 million people died (as of June 2024), with 27.3 million being the central estimate—or 3.9 times the official number of recorded deaths.“Excess deaths” is simply the difference between reported deaths and the number of deaths that would have been expected to have occurred in the absence of the pandemic. The model estimates excess deaths for 223 countries and regions for every day since the pandemic began and is based both on official excess mortality data and on more than 100 other statistical indicators.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Using this model’s central estimate, Canada suffered over 86,000 excess deaths while, comparatively, the U.S. suffered 1.47 million.

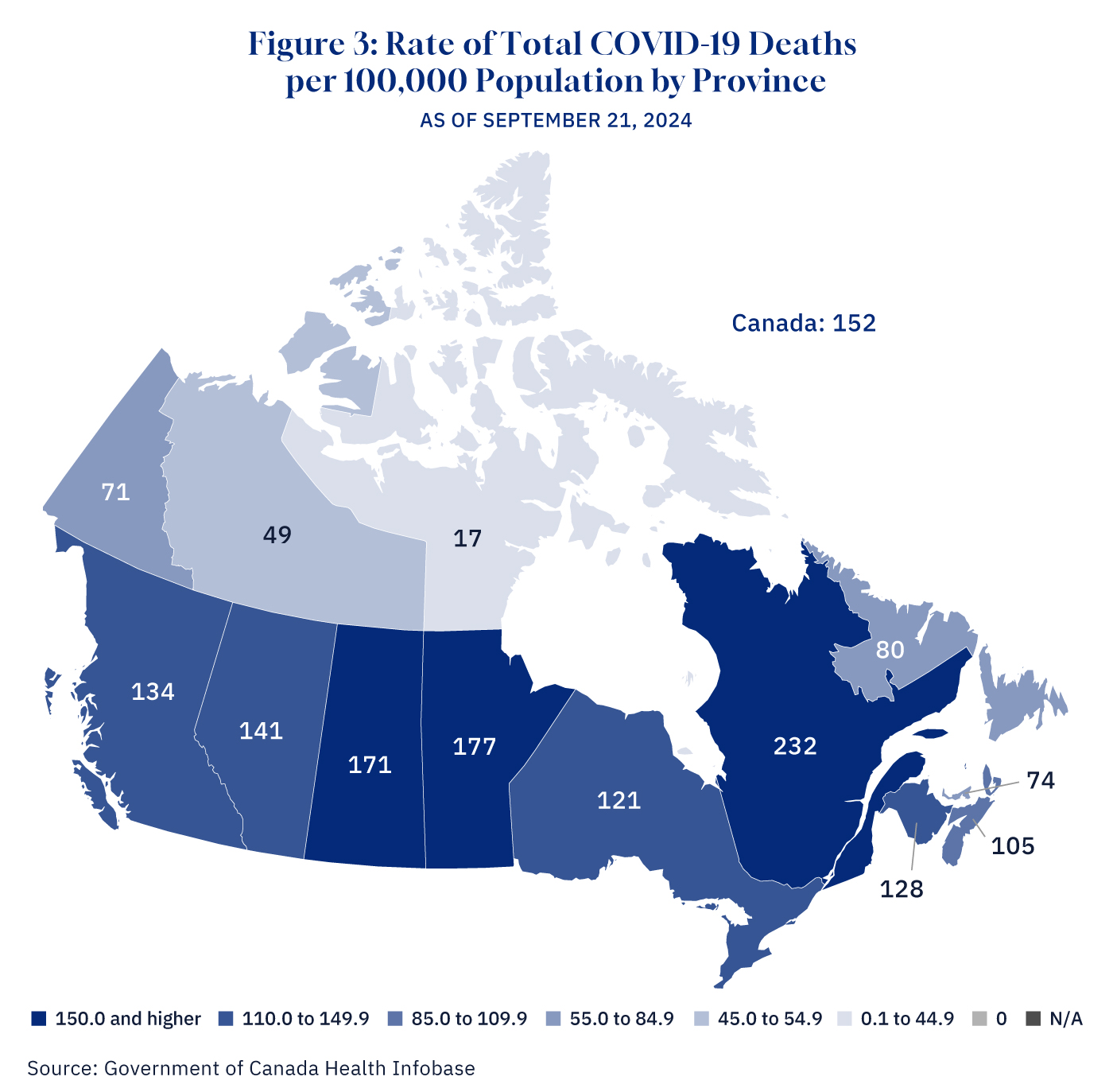

In terms of the death rate, Canada saw 146 people die per 100,000, according to the WHO, and 152 per 100,00, according to the Government of Canada.

While Oxford’s Our World in Data platform calculates estimated cumulative excess deaths per 100,000 at a slightly higher rate, Canada comes out relatively well in comparison to its peers. The country’s rate of 225 per 100,000 is in line with several European countries such as Norway (222), Ireland (247), and Sweden (249). When compared to our fellow G7 countries, Canada ranks first, ahead of France (244), Japan (277), Germany (354), the U.K. (409), the U.S. (434), and Italy (519).

By COVID-19 crude mortality rate, however, Canada did much worse, ranking second-highest compared to 38 other advanced economy peers. Canadians had a 1.1 percent chance of dying from COVID-19, just behind America at 1.2 percent.This mortality rate is calculated by taking total deaths from COVID-19 by June 2022 and dividing by total cases of COVID-19 by June 2022. Iceland was the lowest of these advanced economies at 0.1 percent.While there is no single definition, advanced economies are typically classified as having a high level of per capita income, a varied export base, and a financial sector that’s integrated into the global financial system.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Using the Government of Canada’s Health Infobase to zoom in on Canada, the highest total number of confirmed deaths by province occurred in Quebec, which saw nearly a third of Canada’s total reported deaths at 20,553. By death rate, Quebec suffered 232 deaths per 100,000 people. Ontario was not far behind in total deaths at 18,873, but middle of the pack in terms of death rate, at 121 per 100,000. Prince Edward Island had the fewest number of deaths among provinces at 129, as well as the fewest among the provinces in terms of death rate at 74 per 100,000.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Vaccines

President Donald Trump’s Operation Warp Speed and the development of mRNA vaccines represented the beginning of the end of the COVID-19 pandemic.All told, the U.S. government is reported to have invested at least $31.9 billion USD in developing, purchasing, and producing these vaccines.

Research published in The Lancet finds that in the first year of vaccine availability alone, COVID-19 vaccines are estimated to have saved 20 million lives across the world—a global reduction of 63 percent in total deaths. This includes 15.5 million deaths directly averted by the vaccines and 4.3 million deaths indirectly averted.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

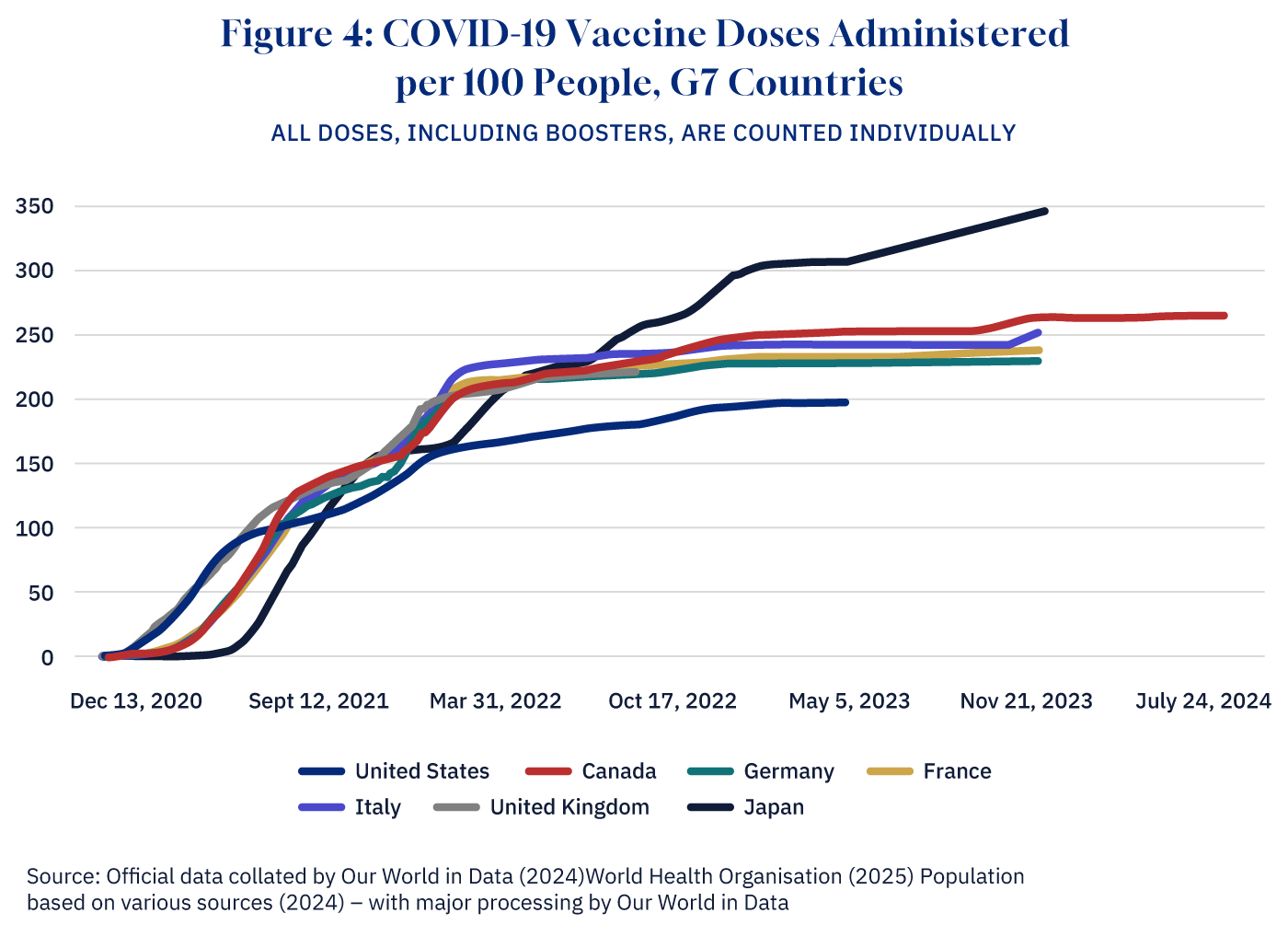

Canada’s initial vaccine rollout, however, was anything but smooth, beginning with an ill-advised Chinese partnership to receive a CanSino vaccine that was never ultimately delivered and cost millions of wasted dollars. Further delays in procuring vaccines put us in line behind peer countries such as the U.K. and the U.S., which only prolonged restrictions and economic disruption.

Canada finally began vaccinating its population in December of 2020. As of June 2024, 107,216,820 vaccine doses have been administered in the country, according to the federal government. Overall, 81.1 percent of the population has received at least one vaccine dose.

$360 billion: The cost of government support

From the outset, Canada followed much of the developed world’s playbook in fighting the pandemic: implementing public health protocols such as masking, social distancing, public and private gathering restrictions, non-essential business closures, and, eventually, vaccine mandates.

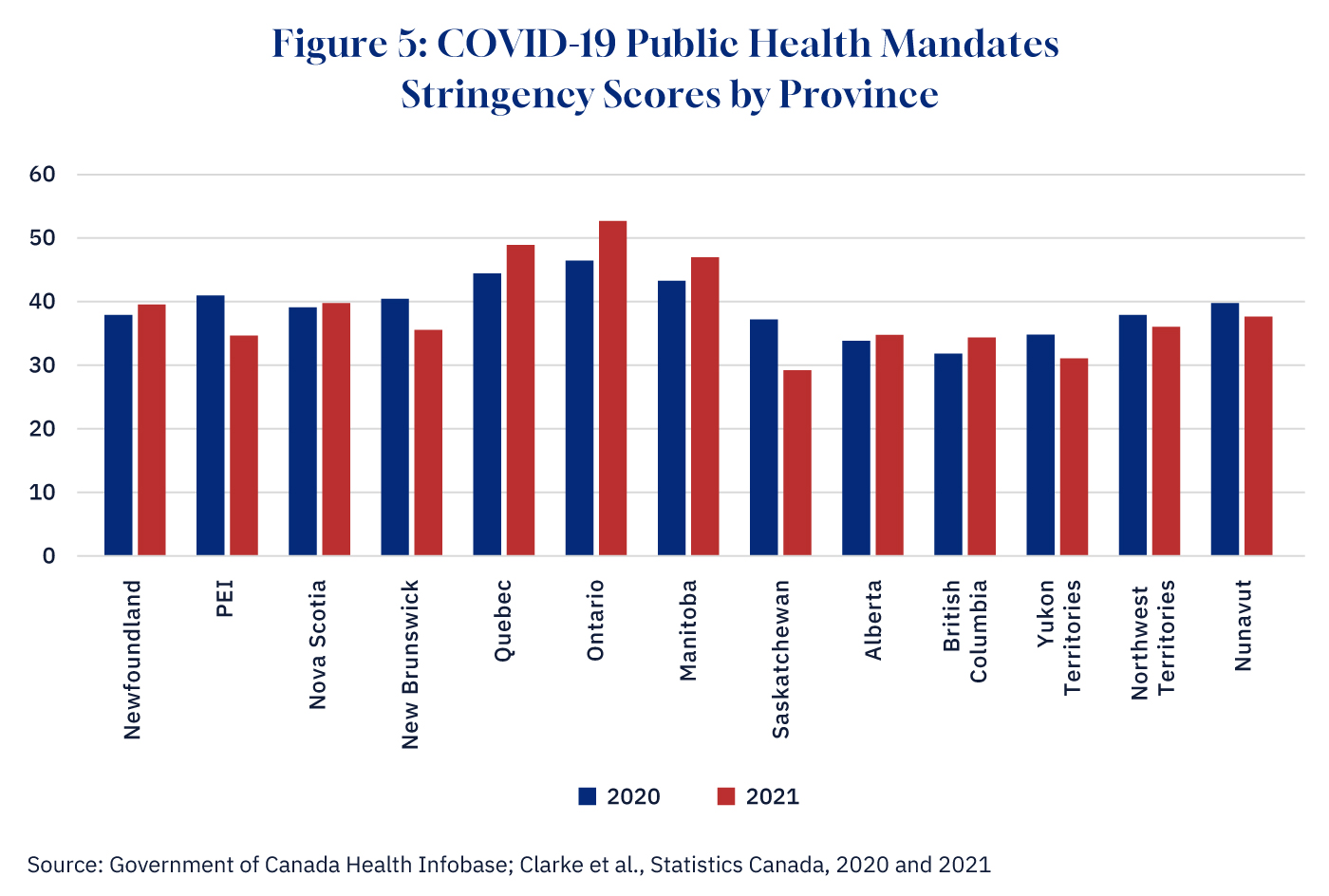

Of its advanced economy peers, Canada had the third-highest stringency score in terms of the level of pandemic restrictions, behind only Italy and Greece.As measured by Oxford University’s COVID‐19 Government Response Tracker.

At the provincial level, Ontario and Quebec consistently had the highest stringency scores throughout the pandemic, while the prairie provinces had the lowest average scores.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Locking down society to such an extent was devastating for Canadian businesses and workers, requiring hundreds of billions of dollars in relief spending. Ultimately, Canada’s federal COVID-19 spending totalled nearly $360 billion through programs such as the Canadian Emergency Wage Subsidy—$100.7 billion—and the Canadian Emergency Response Benefit—$100.4 billion. Of this, the Fraser Institute estimates that, at minimum, 25 percent, or nearly $90 billion, was wasted in poorly targeted spending and overpayments.

The federal government was not alone in this. The provinces also emptied their pockets in the fight against COVID-19, a significant amount of which was also wasted—Ontario’s auditor general, for instance, found that the province had given out $210 million in pandemic relief funds to ineligible businesses.

The federal debt accumulation during the pandemic was substantial. Prior to COVID-19, the fiscal year of 2019-20 ended with a deficit of $39.4 billion, bringing the federal debt to $721.4 billion. In 2020-21, as a result of the pandemic spending, the deficit surged to $327.7 billion, increasing the federal debt to over $1 trillion for the first time, reaching $1,048.7 billion. In 2021-22, the federal government ran another large deficit of $90.2 billion, further raising federal debt rising to $1,140.0 billion. By the end of 2021-22, federal debt was more that 50 percent higher than it was before the pandemic.

Meanwhile, another report found that of 33 industrialized countries, Canadian governments—including federal, provincial, and local—borrowed more money during the pandemic than any other country. This borrowing has added $8.3 billion to present-day interest costs at the federal level.

Large increases in government spending during the pandemic contributed to Canada’s soaring inflation rate, jumping from 0.7 percent in 2020 to 3.4 percent in 2021, 6.8 percent in 2022, 3.9 percent in 2023, and 2.4 percent in 2024.

Overall, as Hub contributor Livio Di Matteo has documented, Canada fared rather poorly across several key measures in terms of COVID-19’s economic impact:

- Canada saw its gross debt-to-GDP ratio increase by nearly 25 percentage points from 2019 to 2021, the 15th-largest increase in the world.

- The country’s unemployment rate in 2020 (9.6 percent) was higher than the world average (9.2 percent), the G7 average (6.6 percent), and the average of the IMF advanced economies (6.3 percent).

- In terms of the IMF’s inflation estimates for 2021, Canada was mid-ranked at 19th-highest amongst 38 IMF advanced economies.

- Canada also had, from 2019 to 2022, the second-worst employment drop of the IMF advanced economies at 5.1 percent.

Was the economic pain of Canada’s pandemic measures worth it in terms of safeguarding public health? That conclusion remains in dispute; one meta-analysis study found that global lockdowns had little effect, only bringing about a 3.2 percent reduction in deaths. And, when incorporating collateral damage from the lockdowns (such as people missing medical appointments or treatments), further research shows that they may have in fact increased all-cause mortality.Another study finds that as an instrument, they may have been too blunt, with mandated behavioural changes accounting for only 9 percent of the total effect on the growth of the pandemic stemming from behavioural changes while the remaining 91 percent of the effect was due to voluntary behavioural changes.

35 percent: The impact on Canada’s youth

The pandemic did not impact everyone equally. While the virus did physically affect older and physically vulnerable populations, young people were asked to bear a disproportionate burden of the pandemic measures relative to their own risk.

The proliferation of learning loss among youth is a representative example of this. Though the virus was far less deadly for kids and youth, school closures to prevent the spread meant they lost out on learning and socializing that will be difficult if not impossible to ever make up.

A UN policy brief found that school closures were estimated to have affected 95 percent of the world’s student population in 2020.

As to the effects of these closures, a 2023 meta-analysis published in Nature reviewing studies from 15 countries found that students lost the equivalent of over one-third (35 percent) of a school year’s worth of learning during the pandemic. In Canada, the Fraser Institute finds that K-12 schools were closed for a minimum of 10 to 27 weeks, depending on the province. Ontario students lost the highest number of days, at 135, while B.C. students lost the fewest at 50.

A 2020 Statistics Canada study found that 57 percent of postsecondary students had academic work placements or courses either delayed, postponed, or cancelled.

School, however, is for more than just learning. A 2021 study by the SickKids Hospital in Toronto found over 70 percent of school-aged children reported a deterioration in their mental health across at least one of six domains, including increased levels of depression, anxiety, and irritability.

The same study found that before the pandemic, 58 percent of youth participated in school sports and/or other extracurriculars, while during the pandemic that number fell to only 27 percent for sports and 16 percent for extracurriculars.

Additionally, the government documented that pandemic measures vastly increased the rate of youth not in employment, education, or training (NEET), particularly in Quebec and Ontario, which had the highest stringency of public health measures in the country.In Quebec, the NEET rate for youth aged 25 to 29 increased from 12 to 16 percent between 2019 and 2021, while Ontario saw 20.7 percent of youth in NEET in 2021 compared with just 14.6 percent in 2019. The annual NEET rate increased by 14 percent for youth aged 18 to 24 across OECD member countries between 2019 and 2020, while Canada, comparatively, saw a 46 percent jump over the first year of the pandemic.Beyond schooling, the government also admits that “in Canada, youth may have been comparatively worse off due to their relatively high concentration in industries that were hit hard by public health measures.”

Children wearing masks sit behind screened in cubicles as they learn in their classroom after getting their pictures taken at picture day at St. Barnabas Catholic School during the COVID-19 pandemic in Scarborough, Ont., on Tuesday, October 27, 2020. Nathan Denette/The Canadian Press.

24 days: The political impacts of a pandemic

The story of any pandemic is incomplete without mention of the social and political tremors that vibrate alongside the medical and economic upheaval. As Daniel Defoe, describing London’s Great Plague of 1665, wrote in his 1722 book, A Journal of the Plague Year:

They heard Voices that never spake, and saw Sights that never appear’d; but the Imagination of People was really turn’d wayward and possess’d: And no Wonder, if they, who were poring continually at the Clouds, saw Shapes and Figures, Representations and Appearances, which had nothing in them, but Air and Vapour.

The COVID-19 era was no exception. Locked down in our homes, the objects of our fascination were not the sky and clouds but our screens and the Cloud. The shapes and figures we conjured out of the air and vapour and algorithms were different than those of plagues past, but they were no less able to compel the homebound doomscrollers anxious for any ember to enflame their angst and pain and paranoia. America saw the Black Lives Matter movement and rioters burn through their cities. In Canada, the unrest was decidedly less violent, if no less dramatic.

It may have been the enduring lockdowns and heavy-handed mask and vaccine mandates that got the wheels rolling, but it was the incompetence—at all levels of government—that kept the Freedom Convoy’s semi-trucks pitched up in downtown Ottawa for approximately 24 days.The caravan of trucks and protestors began arriving on January 28, and the Emergencies Act was implemented on February 14. By Feburary 21 the last of the protestors had moved on. On February 23, Prime Minister Trudeau revoked the use of the act, claiming it was no longer needed.

And it was the Trudeau government’s seismic legislative solution to this problem that will be studied and debated for decades to come, long after most other particulars of the pandemic have faded. The invocation of the Emergencies Act and the furthest-thing-from sunny ways “Canadian authoritarianism” it represented will undoubtedly be a defining feature of Justin Trudeau’s political legacy.

A protester waves a Canadian flag in front of parked vehicles on Rideau Street in Ottawa, Friday, Feb. 11, 2022. Justin Tang/The Canadian Press.

Whether it is this widespread declining trust in institutions, governments, and expertsWhile Canada does score slightly higher than the OECD average in terms of trust in public institutions, Statistics Canada’s 2022 Canadian Social Survey study found that less than a third of Canadians reported a good or great level of confidence in the federal Parliament (32 percent) or the Canadian media (31 percent), compared with 62 percent who reported a good or great deal of confidence in the police. or the persistent rise of populist political movements or the global backlash against incumbent governments or the growing rates of vaccine skepticismMeasles appears to be making a comeback these days, not coincidentally. or the vibe shift, we are still riding out the aftershocks of the pandemic era.

12.5 percent: How permanent were labour market (and other) changes? It’s too early to tell

That being said, whether it’s the massively sped-up advancements in biohealth and vaccines or some other factor that seems entirely utterly irrelevant to our eyes now, what the most consequential and enduring impact of the pandemic will turn out to be remains to be seen—much as Chinese premier Zhou Enlai is purported to have said about the impact of the French Revolution when asked about it in 1972: “It’s too early to tell.”While this print-the-legend anecdote is apparently a victim of mistranslation, the point still stands.

For instance: the pandemic shaped the whole of society in drastic ways, but especially in how Canadians worked. Prior to the pandemic, remote work was a rare occurrence—in 2016, only 7 percent of Canadian workers worked from home most of the time. By necessity, remote work exploded in 2020, rising to about 40 percent at its peak in April.

Surprisingly, however, this trend did not persist as strongly as had been expected during the pandemic, when the in-person office was feared dead. By November 2023, only 20 percent of Canadians were still working primarily from home. One year later, that number had fallen to a mere 12.5 percent, while 11.5 percent had a hybrid arrangement.

It’s a reminder that the received wisdom of how the world will look in the post-pandemic era is difficult to precisely nail down, even now.

0: We were not ready

You were promised five key stats, but here’s a bonus one, and perhaps the most important. It’s the one mentioned at the very beginning of this DeepDive: zero. The Canadian government has not yet launched a national inquiry into the pandemic; there has been no comprehensive federal report examining the country’s pandemic response. What, for instance, were the origins of this pandemic? It matters if it originated in a wet market, or as increasingly looks likely (and was a plausible hypothesis from the start) if it was the result of a lab leak and gain of function research gone wrong. What, no matter how well-intentioned, did we get wrong in our response?

The COVID-19 era was filled with remarkably painful lessons. The least we can do is learn from them.

The federal government’s final SARS report ends with the following:

What the SARS outbreak showed, perhaps more than anything else, is the power of public health. The best current evidence is that without effective public health measures, SARS would have eventually sickened millions of people on this shrinking planet, causing not hundreds of deaths, but countless thousands. The next outbreak, however, may be even more insidious than SARS. Canada may have to deal with a deadly airborne virus, or a virus transmitted via droplets but with such a long incubation period that quarantine would be worthless. Will we be ready?

We were not ready. Now in the aftermath of COVID-19, that warning remains, and that question still stands. The next outbreak could be even more devastating than what we just faced. Will we be ready?