Welcome to Need to Know, The Hub’s roundup of experts and insiders providing insights into the economic stories and developments Canadians need to be keeping an eye on this week.

These price increases are only the beginning

By Trevor Tombe, professor of economics at the University of Calgary and a research fellow at The School of Public Policy

Last week, I estimated the cost of Canada’s phase 1 retaliation against U.S. tariffs on 1,256 items. Since then, the U.S. has imposed 25 percent tariffs on steel and aluminum imports from several countries. In response, Canada and others have enacted a second phase of retaliatory tariffs—also at 25 percent—on approximately $30 billion in U.S. imports spread over 539 items.

Unlike phase 1, which mainly targeted consumer goods and food, this phase primarily affects more industrial supplies and capital goods. While this softens the immediate impact on consumers, rising business costs will eventually push prices higher.

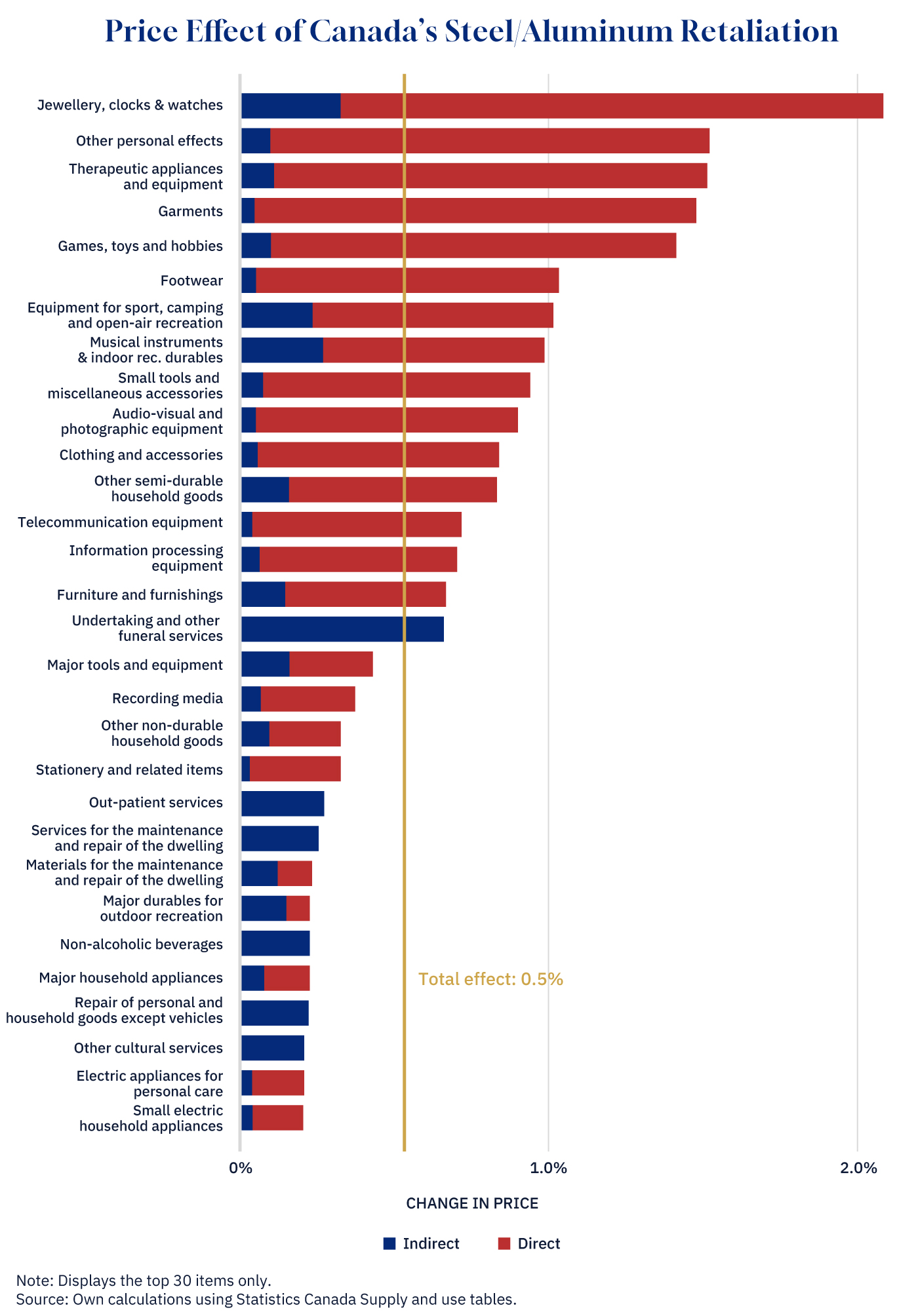

To get a sense of the potential magnitude of the price increases, I have assessed the impact of this second phase on consumer prices using detailed data that tracks product supply, trade flows, and sector-specific economic activity. My estimates suggest these tariffs will add about 0.5 percent to overall household consumption costs. Jewelry, clothing, footwear, and sporting equipment will be hardest hit. Below, I illustrate the effects, with red indicating the direct impact of the tariffs and blue representing supply chain effects as costs are passed down to consumers.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

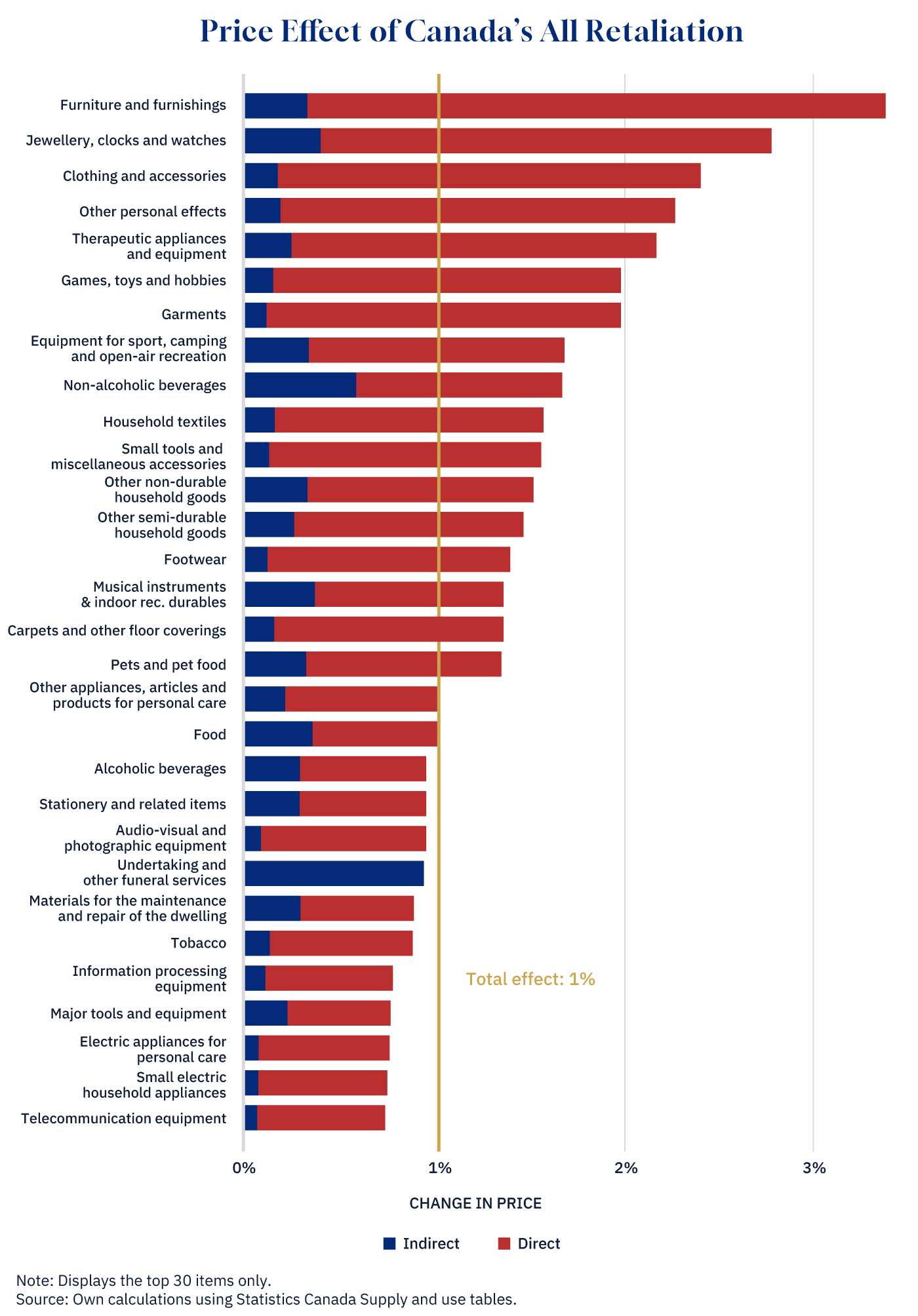

This second phase builds on the first, and when combined, I estimate the total impact on Canadian consumer prices to be an average increase of approximately 1 percent. Some categories are hit particularly hard—furniture prices are expected to rise by more than 3 percent, while food prices, a critical household expense, will increase by 1 percent. Non-alcoholic beverages could see an even steeper rise of over 1.5 percent.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

While these numbers may seem modest, they should be viewed in the context of Canada’s 2 percent consumer price inflation target. A full percentage point increase represents a significant shift. Of course, these effects will take time to materialize, likely over several months.

But as the trade war escalates and Canada continues to respond with tariff measures—as seems likely in two weeks when the next round of U.S. reciprocal tariffs takes effect—the costs will mount.

If this is the start of a prolonged trade war, these price increases are only the beginning.

Carney should think long and hard about the costs of counter-tariffs

By Theo Argitis, The Hub’s editor-at-large for business and economics

At his press conference in London yesterday, Prime Minister Mark Carney made a surprising public acknowledgement: that Canada can’t go toe-to-toe with the U.S. in a trade war.

Asked about how his government would respond to the potential imposition of additional U.S. tariffs, Carney had this to say: “This is a very important question. There is a limit given the relative size of our economies, the extent to which we should match U.S. tariffs.”

It’s an admission of the obvious—one that economists and analysts have been making for weeks, though often drowned out by the noise of the newfound (and overshooting) Canadian economic nationalism that seems to be permeating everywhere.

Canada’s reliance on the U.S. market far outweighs the U.S.’s reliance on Canada. In such an imbalanced fight, a trade war would hurt Canada more than it would harm the U.S. That’s as close to a fact as you get in this debate.

Which raises the question: if Trump goes ahead with his tariff wall anyway, does it make sense to impose any counter-tariffs—even partial ones—that effectively tax Canadian consumers and businesses?

One argument is that even partial retaliation can prevent further escalation. Failing to respond could make Canada look weak and invite even more tariffs. Another is that the U.S. has a lower tolerance for economic pain, and a targeted response might push them to reconsider.

Maybe.

Carney said Canada’s proposed tariffs on about $150 billion worth of U.S. goods are structured to maximize U.S. pain while minimizing domestic impact.

But all retaliation comes at a cost. Canadian consumers will pay more. Indebted households will see borrowing costs rise as inflation ticks up. And if we really believe we can’t deter Trump, we need to think hard and be open about what exactly we’re trying to achieve with any tariffs.

Canada’s climate policy conversation has changed

By Sean Speer, The Hub’s editor-at-large

Pierre Poilievre’s announcement that if elected, he’ll get rid of Ottawa’s mandatory industrial price makes it hard to envision that the Conservative Party can put forward a climate plan that meets the country’s current emissions targets.

The Canadian Climate Institute estimates that the industrial carbon price is responsible for something like 23 to 39 percent of projected emissions reductions between now and 2030. These estimates assume that without the federal backstop, we’ll see provinces weaken the stringency of their own industrial pricing regimes and in turn enlarge the gap between domestic emissions and our international commitments.

Poilievre’s announcement is therefore likely to face criticism from environmental groups and the other political parties. It will be characterized as an abandonment of climate policy.

Yet the reality is that Canada was already behind on its 2030 targets with less than five years to go. Notwithstanding partisan politics, the climate policy conversation has moved onto 2035 or even 2050 targets.

There’s in fact a case that we should move off targets altogether—or at least put them into a broader policy framework.

There are various problems with the overemphasis on national emissions targets that we’ve seen since the Paris summit in 2015. A big one is that it implies that emissions respect national borders. A more globalized conception of climate change might instead recognize that Canada’s optimal contribution may actually involve emissions rising in order to develop and export lower-emitting forms of energy elsewhere.

Another is that sector-specific targets like the Trudeau government’s oil and gas emissions cap create distortions and inefficiencies. If a dogmatic commitment to targets leads you in a direction of an injurious policy affecting Canada’s biggest export sector, it ought to be taken as a sign that the policy objective itself is flawed.

The key point here is that Canada’s climate policy agenda may actually benefit from shifting away from emissions targets and to a broader discussion about what we’re aiming to achieve and how we’re planning to achieve it.

Former Biden administration official Brian Deese has spoken persuasively for instance about “making clean energy cheap rather than pollution expensive.” That would ostensibly involve a different policy agenda, including, for instance, significant public spending on nuclear energy.

Poilievre’s announcement opens the door to this type of reframing of Canada’s climate policy goals. There’s now an onus on him and the Conservatives to step through it and lay out credible plan for the country.

No more dithering on defence

By Philippe Lagassé, Carleton University associate professor and the Barton Chair at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs

Boosting Canadian defence spending to 2 percent of GDP by 2030 (or sooner) will require investments in a number of areas. Military personnel should see their salaries and benefits increased. The government should commit to modernizing aging military infrastructure across the country. Far more money is needed for operations and maintenance, notably for centrally managed equipment. If we’re serious about getting to 2 percent, the national procurement budget that covers parts, contracted maintenance, repair, etc. should be flush with cash. Additionally, we should leverage existing procurement contracts to acquire more capabilities that we could use.

Reaching the 2 percent target, and keeping our defence budget there, further demands that we accelerate our acquisition of new equipment. Parliament must grant the government exceptional authority to buy off-the-shelf capabilities without lengthy competitive processes. Relying on existing rules for urgent operational requirements won’t work; the government needs discretionary authority akin to what’s seen in wartime. This authority should be used to rapidly acquire deployable kit that can be quickly replaced as technologies improve. This authority should also be exercised to speed up the acquisition of major platforms, such as submarines, tanks, helicopters, and early warning and control aircraft.