Mark Carney wants this election to be about Donald Trump. Pierre Poilievre wants it to be about the Liberal record. During Thursday night’s English-language debate, Trump’s name rarely came up. Instead, the leaders tussled over everything from housing policy to street crime to Ukraine.

This advantaged the Conservative leader and disadvantaged the Liberal leader. Poilievre didn’t really win the debate. But Carney probably lost it.

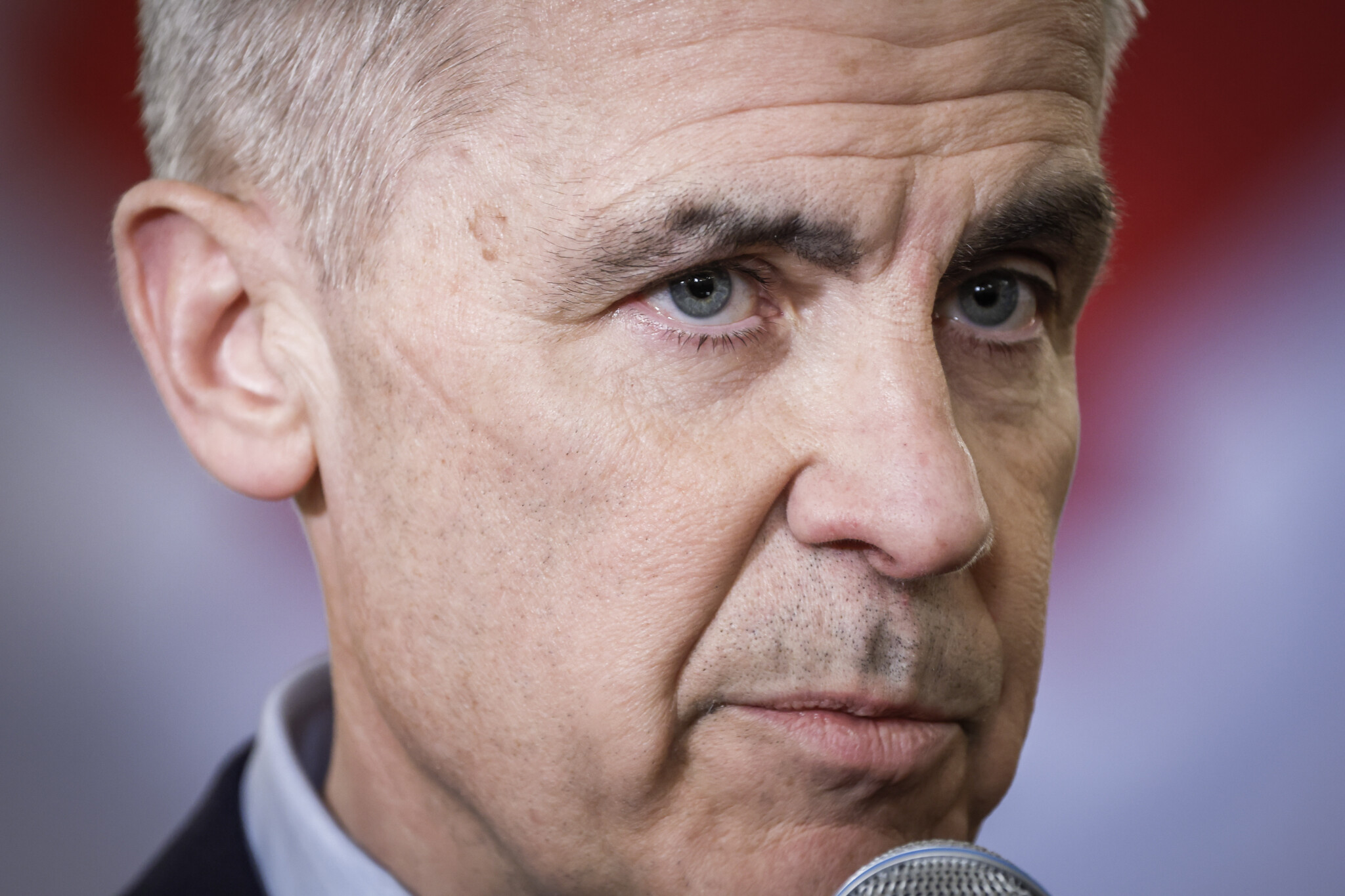

The former central bank governor did give a more assured performance than you might expect from a rookie politician. He kept his temper, made his points, though he tended to tick off those points on the fingers of his hand, like a professor getting through a lecture.

“Three quick points” is not a good way to begin an answer to any question. Also, when uncertain, Carney has a tendency to “ummm” and “humm.”

But the Liberal leader engaged effectively with other leaders on the stage and with moderator Steve Paikin. He actually appeared more informal, less scripted, than Poilievre.

He even got off a couple of good lines, at one point telling Poilievre, “You spent years running against Justin Trudeau and the carbon tax. They’re both gone.”

Poilievre was most successful when he hung Trudeau’s legacy around Carney’s neck. He accused the Liberal leader of being almost a figurehead, fronting a Liberal Party whose policies had become deeply unpopular.

At one point, the Conservative leader said that Trudeau’s former staffers were in Montreal writing Carney’s talking points. “I do my own talking points, thank you very much,” Carney retorted. But it was point Poilievre.

While Carney generally spoke to Paikin when answering questions, not looking at his opponents when confronted by them, Poilievre spoke mostly to the camera. This approach doesn’t work for me, though I’m probably wrong. Political strategists insist the direct-to-camera approach can be very effective. It’s one former prime minister Stephen Harper was known for.

Poilievre also had a tendency to end his statements with his signature slogans, “Bring it home” or “For a change,” which is just cheesy.

But he avoided the pitbull persona, to his advantage. And he spoke on topics close to his heart. He got to say, “While the Liberals are focused on the rights of criminals, a Conservative government will focus on the rights of victims,” and other signature messages.

Since most of the debate was on domestic policy, that made it possible for Poilievre, over and over again, to dredge up the Liberal record. The girls and boys in the Tory war room must have been grinning.

Jagmeet Singh delivered a feisty performance, not hesitating to interrupt and talk over other leaders on the stage. The polls show his party at risk of oblivion, so he had to swing for the fences.

Bloc Québécois leader Yves-François Blanchet should not have been on that stage. The Bloc, in this writer’s opinion, should be limited to the French-language debate.

The organizers of the debate were right, even if they acted belatedly, in keeping the Greens out of the debates entirely.

In election campaigns, leaders’ debates don’t matter, unless they do. Anyone who was around at the time, or who reads their history, knows that Progressive Conservative leader Brian Mulroney scored a direct hit against Liberal leader John Turner in the 1984 leaders’ debate, over Turner’s decision to make numerous patronage appointments directed by outgoing prime minister Pierre Trudeau.

“I had no option [but to make the appointments],” Turner said. “You had an option, sir,” Mulroney shot back. “You could have said ‘I am not going to do it.’” Turner never recovered.

Going into the 2015 debate, many people thought NDP leader Tom Mulcair was the leader most likely to unseat Stephen Harper’s generally unpopular Conservative government. Liberal leader Trudeau was given little hope.

Trudeau went after Mulcair for saying 50 percent-plus-one would be sufficient in a referendum for Quebec sovereignty. Trudeau, citing the Clarity Act and a Supreme Court ruling, said a more substantial majority was required. What size must that majority be? Mulcair asked repeatedly. “What’s the number, Justin?”

“You want a number, Mr. Mulcair? I’ll give you a number. My number is nine,” Trudeau retorted.

“Nine Supreme Court justices said one vote is not enough to break up this country.” From that moment, people started taking Trudeau seriously.

This debate will not enter these annals. It is unlikely to substantially move votes away from other candidates toward Poilievre. But it’s hard to see how it advantaged Carney. It’s never a good night when you spend much of the time trying to convince people you are not Justin Trudeau.