Governing Canada has never been easy.

From Confederation onwards—if not for generations before—managing regional tensions has been one of our central challenges.

Today, concern around the “fair” allocation of federal finances is one of the main flashpoints, followed closely by demands for greater infrastructure.

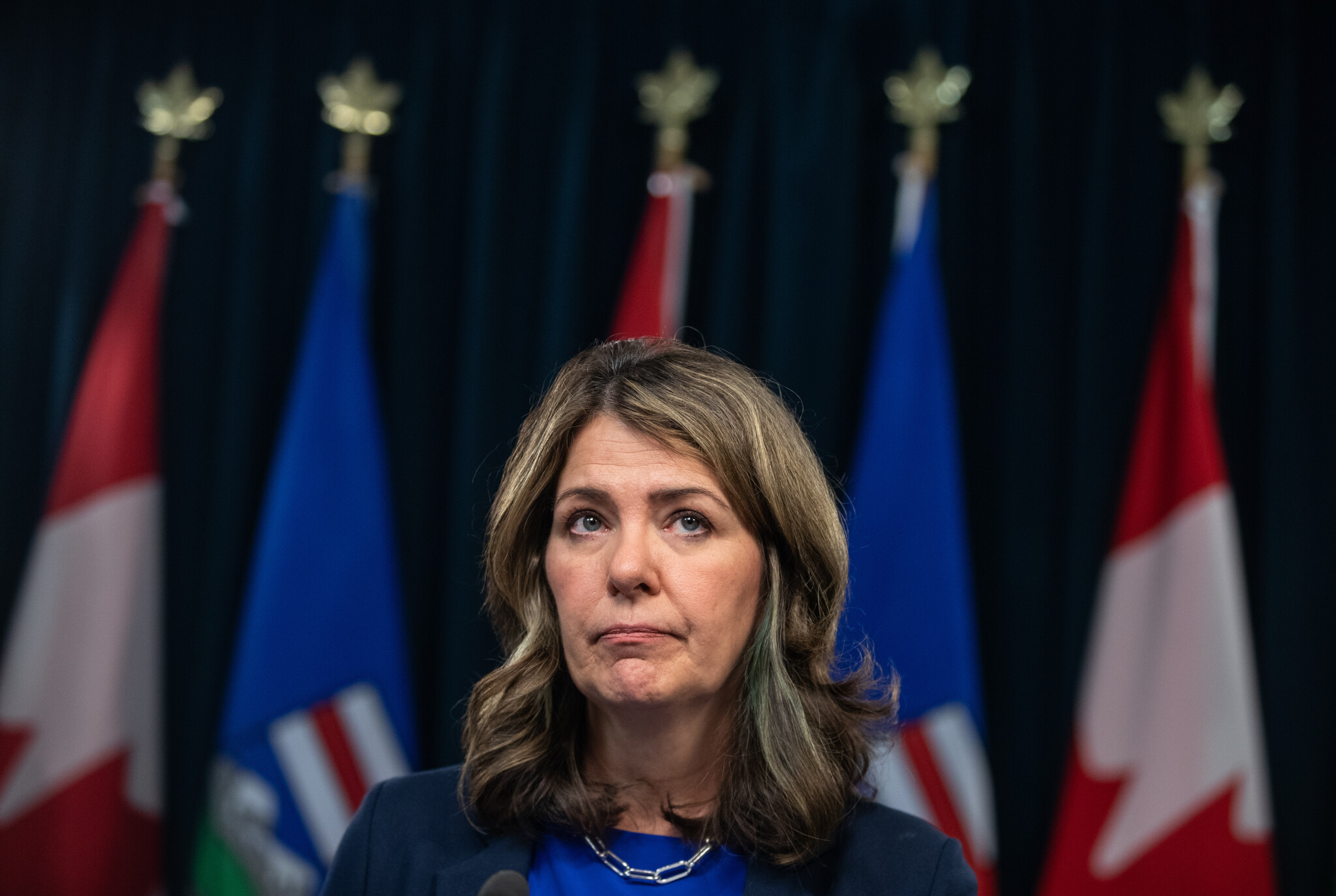

Newfoundland and Labrador has taken the federal government to court over the equalization formula, and in a recent televised address Alberta’s premier Danielle Smith called for eliminating uneven transfers between the four largest provinces; saying there is “no excuse for such large and powerful economies like Ontario, Quebec, B.C., or Alberta to be subsidizing one another.”

Following Premier Smith’s address, much of the focus has been on the issue of rising separatist sentiment in the province, with now roughly one in three residents expressing support for leaving Canada.

But separation can distract from more concrete issues the provincial government has with federal policy. Issues that it hopes to raise directly. The province will create a special negotiating team to engage with Ottawa over infrastructure, emissions policies, transfers, trade policy, and more.

While many might want to avoid any talk of an “Alberta Accord,” perhaps out of concern it legitimizes separatists in the province, that would be a mistake.

Whatever one thinks of the specific points raised by Alberta’s government, managing regional tensions is an important way in which we govern ourselves in this highly decentralized country. Time and again, federal policy has responded flexibly to regional concerns. Not always, of course, but often—even when the rhetoric of provincial political leaders gets a little out of hand.

Federal-provincial fights are normal

Debates over federal transfers are a good example of this. At some point or another, leaders from nearly all provinces representing nearly all political parties have raised heated concerns over federal transfers.

One premier (a Liberal one from Ontario, to be clear) once called the equalization program “perverse and nonsensical,” and several other provinces have taken the federal government to court over it, from the Social Credit in B.C. to the NDP in Saskatchewan.

Sometimes, provinces make dramatic symbolic gestures to show just how frustrated they are. Joey Smallwood, Newfoundland’s first premier after joining Confederation, once draped government buildings in black, flew flags at half-mast, and declared the province in mourning after talks with Ottawa over fiscal arrangements broke down. (A crowd then burned Prime Minister Diefenbaker in effigy.)

Less well known to many Canadians today is that these conflicts even predate Confederation itself. Upper and Lower Canada spent decades fighting over how to divvy up tariff revenues. The British Parliament had to step in more than once. At one point, Upper Canadian leaders even tried to annex Montreal to gain access to a port (and other reasons). Even implicit redistribution received its share of attention. George Brown, one of the Fathers of Confederation, often complained that Canada West (i.e., Ontario) contributed three-quarters of the united province’s revenue but received only half the spending.

Nova Scotia’s Joseph Howe even led Canada’s first separatist movement, arguing that the province had been shortchanged.

Ottawa responded with “better terms” that helped ease tensions. And this early example of how federal governments respond is notable.

Why federal flexibility matters

Time and again, when tensions flared, Ottawa adjusted. From special grants to Manitoba, to generous early terms for Alberta and Saskatchewan, to increased debt allowances for Ontario and Quebec, the list goes on. And today, even equalization goes through significant reforms in response to provincial demands. Today’s formula, after all, exists in no small part due to former prime minister Paul Martin’s response to concerns raised by Newfoundland and Labrador.

This history doesn’t mean provincial concerns are always justified—but it does mean they’re normal. It’s baked into the very nature of our federation. Canada is vast and highly diverse. Federal policy can’t possibly satisfy every region, every year.

That’s why flexibility matters. A federal government that refuses to respond to regional pressures is the exception, not the rule. Special arrangements—tailored to regional realities—are a vital part of keeping the federation together.

Today, Premier Smith’s recent address reminds us once again just how deep those tensions can run. Whatever one thinks of the merits of the premier’s concerns, her remarks tap into longstanding frustrations over federal finances, energy policies, and infrastructure.

The federal government has responded to such frustrations in the past, and today should be no different. An “Alberta Accord” or something similar may very well be a useful and necessary step forward.

Roll up our sleeves and get in there

Canada’s regional diversity is not a weakness, but an asset.

Even when such diversity causes tension and, dare I say, alienation, it can be a good thing.

Former prime minister Pierre Trudeau thought so, at least. Regional loyalties naturally develop, he observed in 1969, and central government policies will always involve “making some allocation of resources which means we’re taxing one part of the country to help another; or putting tariffs on one part of the country to help another…this is inevitable in a country of this size.”

But he wisely noted that the danger to Canada is in only looking at policy through the lens of “one regional point of view.” Something both federal and provincial governments have been known to do.

The challenge for our political leaders is to recognize moments of tension as opportunities to both understand unique regional concerns and to try and address them.

For Trudeau senior, the solution was not to break up the country, but to “roll up our sleeves and not just gripe and bitch, but get in there…”

The call for negotiations around an Alberta Accord may be an opportunity to do just that.