While the broad 25 percent tariffs once floated by President Donald Trump never fully materialized, Canada’s retaliatory measures—covering over 1,800 U.S. product lines, representing more than $90 billion in Canadian imports from the U.S. last year—remain largely in place.It’s worth noting, however, that this figure slightly overstates the impact, as some of these tariffs don’t apply to goods that meet the terms of NAFTA 2.0. Though some exemptions and supports have softened the impact (and created confusion), the economic consequences of these tariffs are starting to take shape.

Newly released trade data for April 2025 allow us to take a detailed look at how Canadian imports have shifted in response.

The numbers reveal a sharp drop in goods targeted by retaliatory tariffs. In contrast, any effect of the broader consumer-led boycott of U.S. products is harder to detect.

Though not for lack of trying. Many Canadians chose to boycott American products in favour of local or non-U.S. alternatives. Grocery stores capitalized on the moment, heavily promoting “buy local” campaigns.

Some product categories, as we’ll see, did experience notable declines—but even there, the broader economic impact on the United States appears limited.

But first, let’s look at where the effects of retaliation are clearest: products that were explicitly targeted by Ottawa’s retaliatory tariffs.

Canada’s retaliatory tariffs

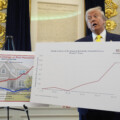

Comparing import values for items targeted by Canada’s 25 percent tariffs with those that were not, the difference is striking. I find that imports of tariffed items in April 2025 were nearly 43 percent lower than the same period in 2024, while imports of items not tariffed declined by just under 8 percent over that time.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

But from an economic standpoint, does this drop matter to the United States?

In dollar terms, the decline in April alone represents about $3.8 billion in missed Canadian purchases from U.S. firms. While that sounds substantial, the scale of the U.S. economy puts it into perspective: with a nominal GDP of nearly $30 trillion USD—or about $41 trillion CAD—this loss amounts to just 0.1 percent of monthly economic activity.

The limited economic hit was widely expected, of course, but for the first time we now have data to start measuring it. And these early signs suggest the impact on the U.S. economy is minimal.

The effect of buying local

But what about consumer boycotts?

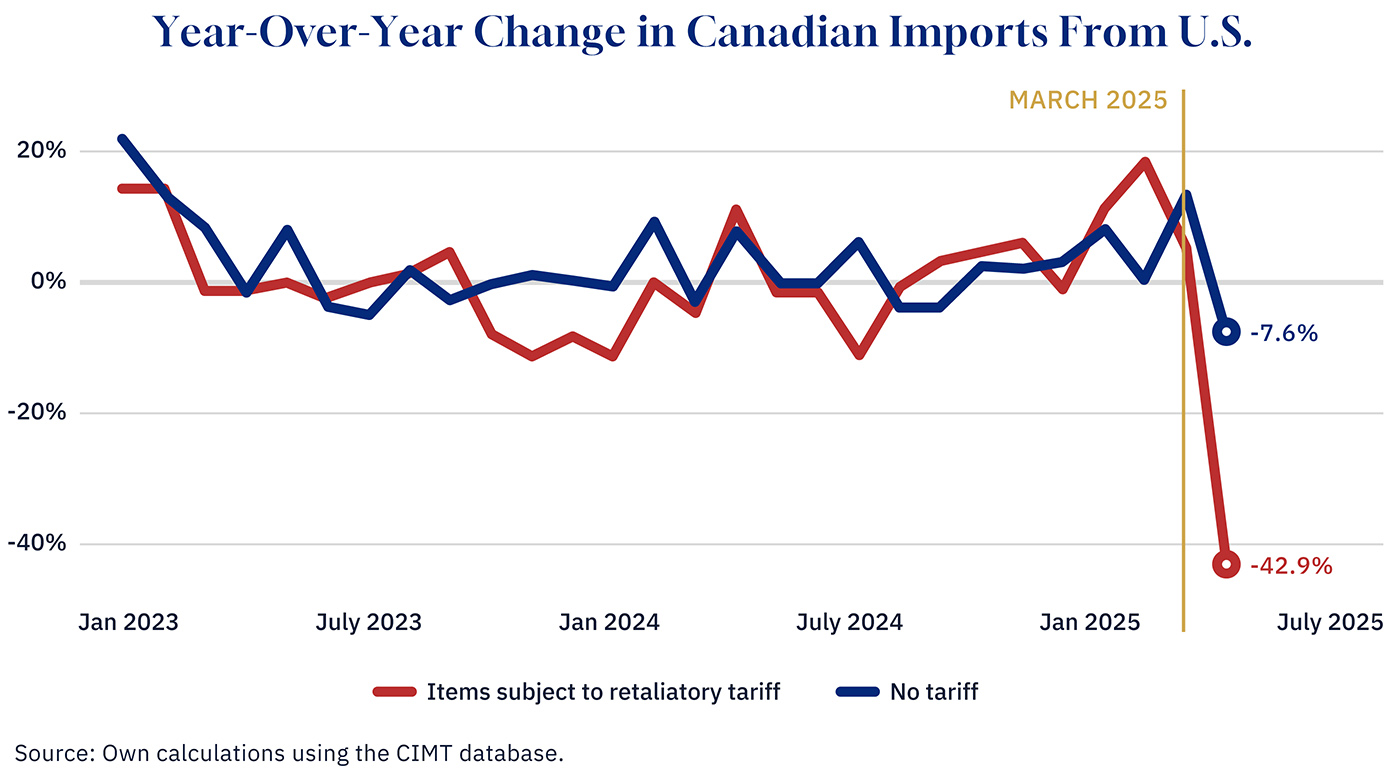

In certain categories, government-led boycotts produced visible results. Wine is the standout case. Several provinces, which directly control alcohol sales, removed American wine from shelves. While some provinces, like Alberta and Saskatchewan, have since reversed course, the initial effect was dramatic: wine imports dropped off a cliff.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

That said, wine was also subject to retaliatory tariffs, so it’s hard to separate government action from consumer sentiment. To isolate the effect of consumer boycotts, it’s helpful to look at product lines that were not subject to tariffs but still experienced sharp import declines.

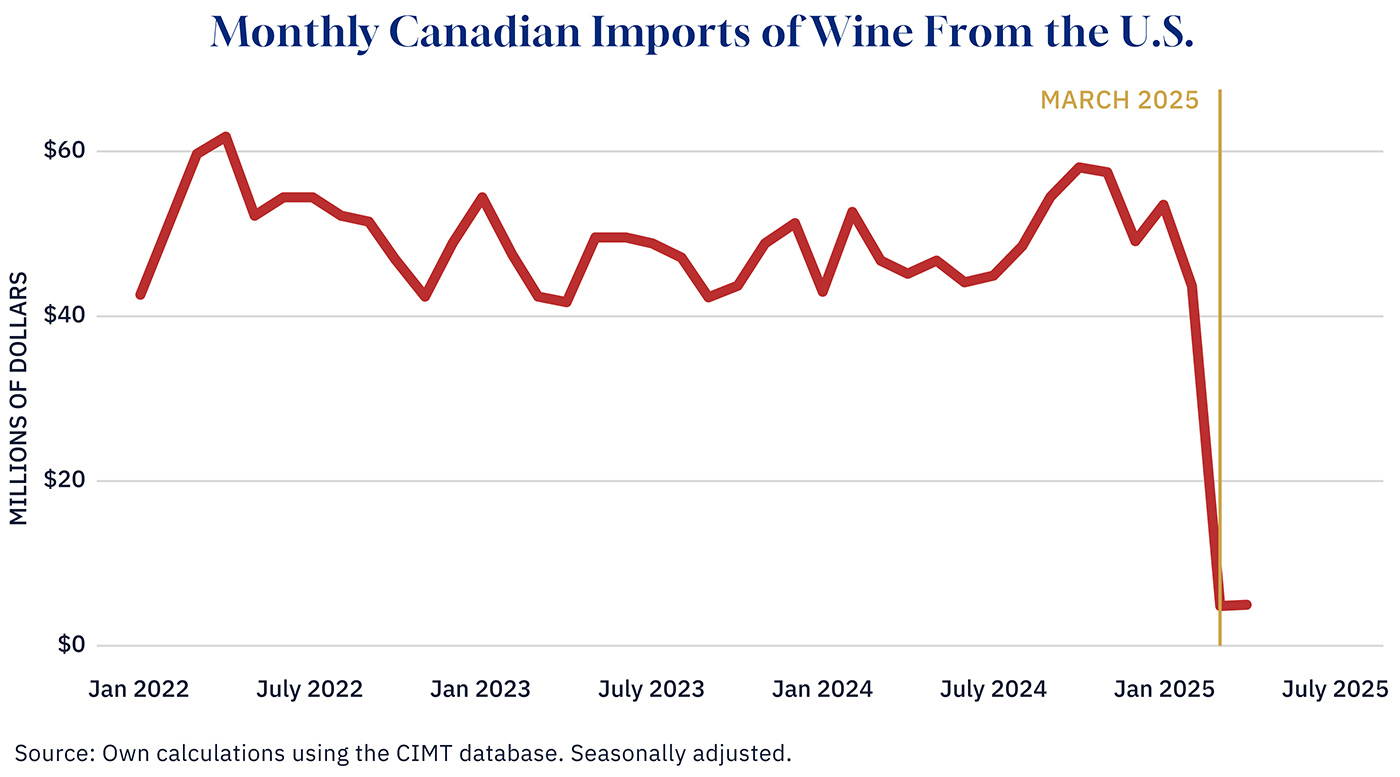

A few examples emerge. Prepared cereals (think corn flakes and the like), excluding items subject to tariffs, showed a marked drop in import volume. Perhaps Canadians changed up their breakfast habits? But given past volatility in this category, it’s wise to interpret this cautiously.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

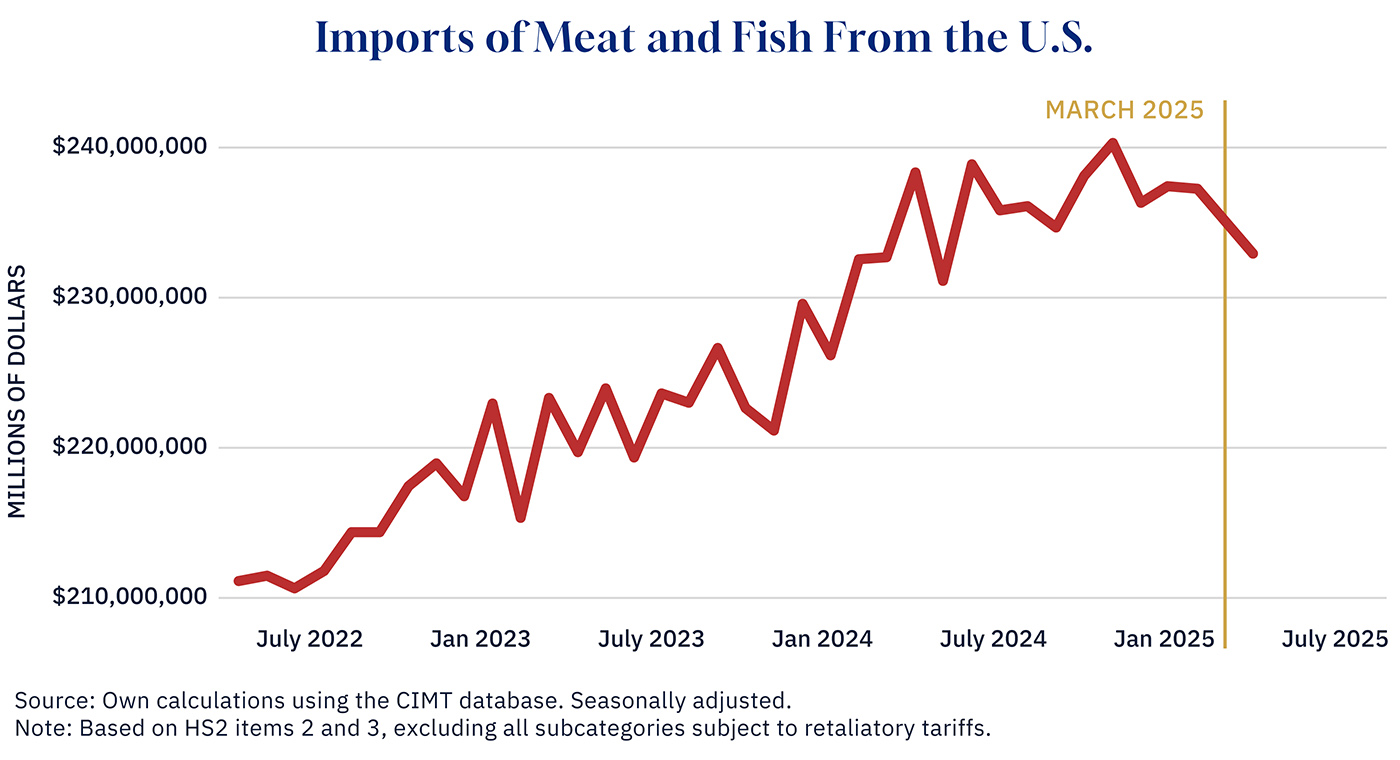

Meat and fish are another area where imports declined slightly—though, again, the change may fall within the range of normal month-to-month fluctuations.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Negligible effects, so far

There are undoubtedly other product lines that saw declines. But after several hours spent combing through thousands of separate data points, I can’t find clear evidence of boycott-driven changes. Perhaps it will just take more time for shifts in consumer spending to affect store inventories and, ultimately, imports. And perhaps I just missed a few more interesting cases.

Either way, even in areas where I found an effect, those were modest. In April, meat and fish imports were down just $4.5 million from January. Prepared cereals fell only $3 million over the same period. In the aggregate, whether April’s numbers for imports of non-tariffed items are lower than January’s also seems to depend on how the data is seasonally adjusted.

In short, government measures—like removing U.S. wine from store shelves or imposing tariffs—had clear, measurable impacts. The same cannot be said of consumer boycotts. While individual choices may have shifted behaviour at the margins, the data reveal no consistent or large-scale changes in imports outside of tariffed goods.

More data in the months ahead may tell us more. But for now, the conclusion is clear: while retaliatory tariffs had measurable effects on Canadian trade flows, and consumer boycotts—however well-intentioned—reflected genuine public anger with the U.S., neither has yet produced any meaningful economic impact south of the border.