I once flirted with a redcoat on the plains of Fort York.

The City of Toronto-owned Fort York National Historic Site used to showcase its redcoat guard reenactors clad in historically-accurate uniforms carrying muskets, demonstrating drills and warfare on the hour, hanging out with visitors, posing for selfies, answering questions about military life of the era.

That era resonates in so much culture to this day–the Napoleonic Wars, the setting of the movie Master and Commander, Tolstoy’s War and Peace, Jane Austen’s books, and of course, the War of 1812, the original reason for the fortress in the muddy York. The trained animators at the museum even counted the odd female soldier in their number: tall, lanky ladies who could sport the uniform well and didn’t mind the frequent cannon explosions. I took a picture of one of them one time, and the rest was awkward flirting.

But then the city decided to cancel the redcoats. Soldiers were cancelled at the military museum at Fort York. No good explanation was offered as to why. Given that the change took place between 2021-22, at the peak of the woke terror in our cultural institutions, you could legitimately surmise that historical animators with muskets became the evil forces of colonization practically overnight. They have not since returned.

Around the same time, the geniuses of the city’s Economic Development and Culture department decided that a stone portrait of Christopher Columbus should be removed from a park of historic ruins. And in 2022, our history museums abandoned Christmas programming, only their most popular and busiest. “Somebody dropped the ball,” suggested one councillor, but I would bet it was intentional: Christmas, Victorian or otherwise, became too “settler-y.” It took two more years for the words “Christmas” and “Canada” (as in Canada Day) to make a relative comeback.

When I visited the museum at Fort York’s website in 2021, it had, like many other institutions at the time and some still to this day, a prominent “since time immemorial” land acknowledgement. (As late as last year, the Royal Ontario Museum Walks would start with the guide reciting the “time immemorial” land acknowledgement. I haven’t attended since last year, but it could still be happening.) So native people did not come from Asia via the Bering Plain, between 20,000 and 10,000 BC, but rather the Creator put them there separately from all other homo sapiens who migrated from the African continent? Today, thankfully, this is no longer features on the Fort York pages, though guided tours through the city museums still start with a land acknowledgement, even if you’re just looking to see the print machine at William Lyon Mackenzie’s House.

Visitors at Fort York in Toronto on Friday, June 27, 2014. Nathan Denette/The Canadian Press.

What’s the point?

As a frequent visitor, I can attest that Toronto’s history museums are coming out of the struggle session era scarred, discombobulated, and in search of a purpose.

Most stayed shut longer than was necessary after COVID-19. The open hours returned timidly, and only by online appointment. Today, the city’s history museums are open to the public five or six hours a day, maximum, five days a week. No audio guides exist for anyone wanting to wander through on their own, no glossy brochures, though you may get a printout to read. There are no cafés anywhere near these museums, and you are positively discouraged from lingering.

The Mackenzie House, the Bond Street Georgian where William Lyon Mackenzie lived and printed The Colonial Advocate, has been closed for restoration for years, with no updates for the public. Montgomery’s Inn in Etobicoke is a shell, a full-on rental venue with its upstairs inaccessible due to dilapidation. If you come for historical information, you can read from a printout and show yourself around.

I have been puzzled and fascinated by what’s been happening to the Spadina Museum in recent years. Former residence of James Austin, the founder of the Dominion Bank and Consumer Gas, and several generations of his family, Spadina, with its gardens and orchards, is one of the most attractive places to visit in Toronto.

When I took the first post-COVID-19 tour in October 2021, the first thing the guide told us was, “We are working towards greater understanding of our history and consulting the Indigenous elders as we aim to decolonize the museum.” How do you decolonize a museum that’s funded through property taxes?

The absurdity went unnoticed by the city’s Economic Development and Culture managers, who suddenly became embarrassed by the fact that until as late as the 1970s, things in Toronto were built largely by people of Scottish, Irish Protestant, English, and French descent. “Can we rework our own city’s 19th century into something more DEI? Let’s just graft all sorts of BIPOC content into existing museums and call it ‘Awakening’!” I expect that’s how the thinking, if any, was taking place, went.

Please note, this kind of intervention could be done well. Commissioning videos and projecting images on facades can be attractive. Some of these videos that the city commissioned are actually intriguing pieces of experimental and political court-metrage. (Just ignore the art-speak-wokery that accompanies them.) I particularly liked Sonya Mwambu’s experimental video in which Spadina House is owned by a black family with black servants, every shot superimposed on the artifacts from the past, to the oneiric effect. The performance by Karimah Zakia Issa, pondering connections between Mary Ann Shadd Cary and Mackenzie, was also interesting.

But disregarding the actual stories of these houses and inventing stuff? Much less so. For the big chunk of 2023, if you visited Spadina Museum, you had to look at paintings of famous Toronto Raptors on its walls. Namely, the museum had asked a black artist to reinvent the house in some way, and this ended up including a lot of paintings of basketball players. A couple of these portraits were indeed both beautiful and fitted well—the portraits of two unnamed lady friends were where I lingered the longest—but to experience Spadina House reinvented as a Raptors tribute abode was to experience an incongruous, self-loathing mess. With a touch of sadism, the family photos of the Austins on various mantelpieces and dressers have been turned to face the wall. The top floor, where in prior years you learned about the servants and the Austin offspring who lived in the light and airy space, trying to recover from tuberculosis, was emptied out.

I haven’t gone back since, but I’m weary. I see the current tour promises information about “Toronto’s 2SLGBTQIA+ histories,” and given that there is no evidence that any lesbian, gay, or bisexual people ever lived in Spadina House, this too will have to be awkwardly grafted on. I have since visited various similar historical houses—Samuel Johnson’s in London, the Necchi Campiglio Villa in Milan, Victor Hugo’s in Paris, Parkwood Estate in Oshawa—and tried to imagine what it would look like if those houses suffered a bout of self-annihilating ideological fervour. I couldn’t; this seems to be a very Toronto bug.

The future of history

I still hope to learn more about James’ grandson Percy Austin, for example, if Spadina House would take an interest. The First World War volunteer returned home shell-shocked and spent the days after his return hidden away in Barrie. Once back in his family home in Toronto, he stayed in his room, obsessively listening to the radio. He rarely left home. This could be the basis of a tour that talks more broadly about Canadian men in the First World War.

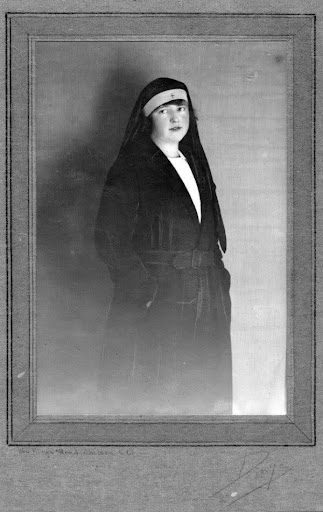

Or why not spotlight Constance Margaret Austin, the granddaughter, who also volunteered to go to war and served as a nurse’s aide. She never married. Sparse records of her life remain, and when she died in the mid-1960s, the obituaries were stingy. No letters or diaries survive? Other siblings did not write about her, not even Anna Kathleen (d. 1983), who bequeathed the house to the city? Is anyone still looking?

Pictured above is Constance Margaret “Margie” Austin, circa 1917.

What about the servants? Why not try to imagine servant lives, Mrs Pipkin’s, for example, who worked as a laundress for the Austins in the 1870s, and leave the Raptors out of it? Which of the aged servants (who were mostly of Irish descent) did the Austins, in the era before old-age pensions, support in their dotage, and which returned to their home towns in Ireland? Years ago, during the Downton Abbey craze, the Spadina Museum offered upstairs-downstairs tours featuring the two very different classes sharing the household. Why not bring something of that sort back?

As for the future of Toronto’s history museums, I don’t dare predict. Those that survive will probably turn into community centres offering things like crafting and cooking classes, and programs of the kind that the libraries excel at. Others will become full-time wedding venues. It would take determination and love of history and culture to turn the boat around—the kind of determination and love that the city’s culture department hasn’t shown in years.