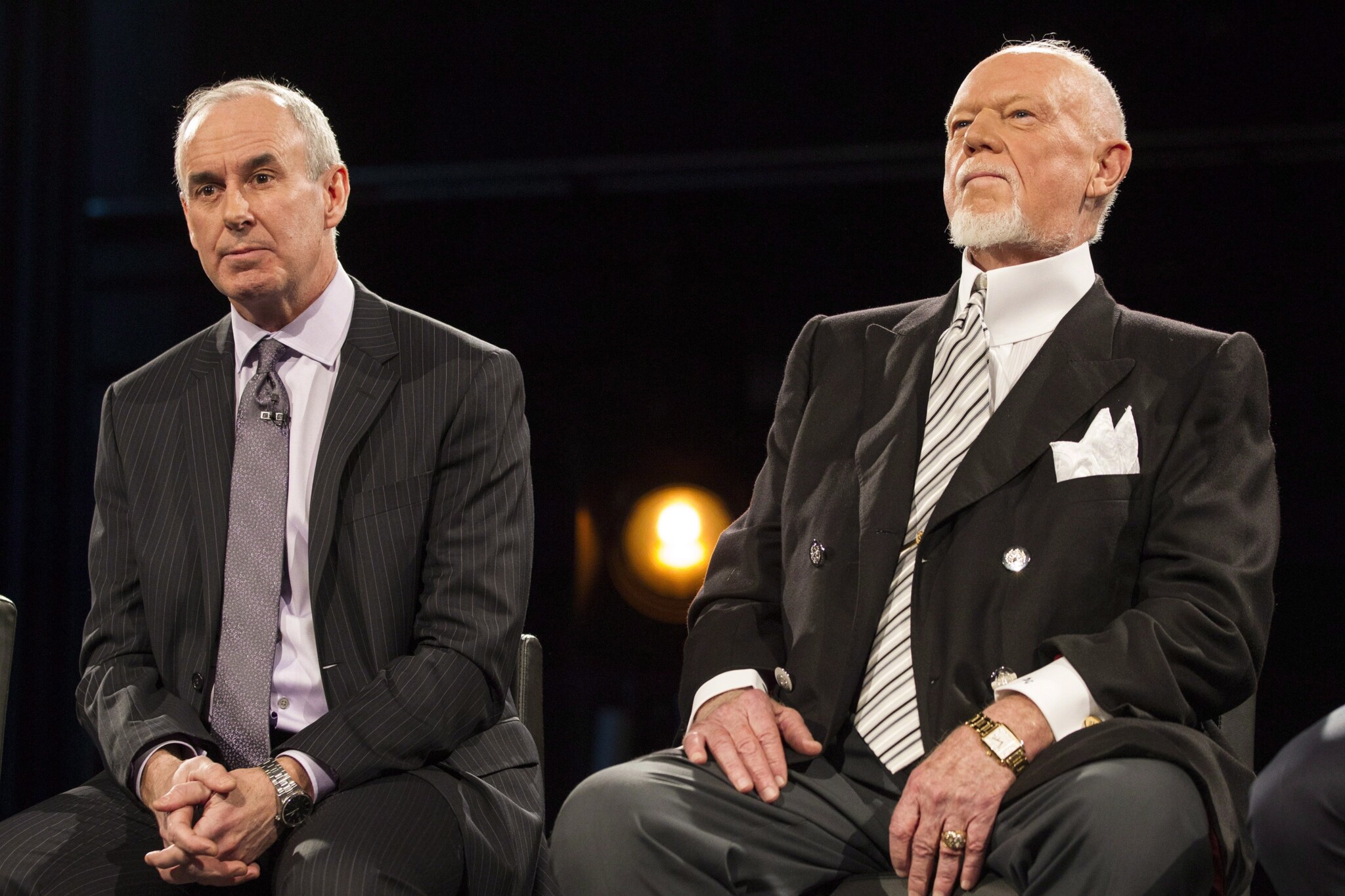

It’s hard not to feel a bit saddened by the latest chapter in the long and complicated saga of Don Cherry and Ron MacLean.

News has quietly circulated that Cherry may be winding down his podcast, Grapevine, and stepping back from public life amid declining health. For those of us who grew up with Coach’s Corner as a fixture of Saturday night life in Canada, it feels like the end of an era. Love him or loathe him, Cherry was a singular personality: brash, unfiltered, often maddening, but also deeply rooted in a particular corner of Canadian life. As I recently wrote, his departure is worth a moment of national reflection, regardless of one’s politics or views on his broadcasting legacy.

BREAKING— Cherry disputes MacLean's claim 'Poppygate' was TV exit strategy | Toronto Sun https://t.co/nK6ju1W5Od

— Joe Warmington (@joe_warmington) July 12, 2025

Which is why it’s so odd and regrettable that MacLean, his long-time broadcasting partner and co-host, used what was ostensibly an opportunity to reflect on Cherry’s legacy in a local newspaper interview to instead relitigate the circumstances of his firing and air grievances about their working relationship. The piece reads less like a tribute and more like a tidy effort at reputational self-management. It’s a bizarre instinct that’s uncharitable at best and narcissistic at worst.

I spent time with MacLean several years ago and found him charming, thoughtful, and interesting. He was a quintessential Canadian public figure: gracious, measured, and deeply knowledgeable about the sport and its culture. But something changed. In recent years, MacLean has become a different kind of figure altogether—one who now embodies the same cultural tensions that are increasingly defining Canadian public life.

His on-air persona has come to resemble an avatar of the Trudeau-era sensibility: inauthentic, performative, and mostly concerned with moral posturing. His commentary feels scripted not in the sense of being rehearsed, but in the way it adheres so closely to the progressive orthodoxy that’s come to dominate our public institutions. What once seemed like principled moderation now reads more like a predictable and tired recitation of identity politics clichés. It’s become exhausting, especially when compared to the dynamism and innovation offered by other hockey broadcasts.

His recent comments about Cherry—including the notion that Cherry’s views “feel good in his world”—are particularly revealing. There’s an implicit worldview at play here: that there are two worlds, one populated by the good and the enlightened, and another by those who, while perhaps not evil, are certainly outdated, problematic, and ultimately dangerous. MacLean’s comments reflect a kind of soft moral absolutism. They suggest that disagreement isn’t just a matter of taste or temperament; it’s evidence of being on the wrong side of history.

This is the same type of worldview that came to define the Justin Trudeau government in its second and third terms: a self-assured progressivism that divides people into right-thinking and wrong-thinking, the righteous and the retrograde. It’s the mindset that allowed the prime minister to treat the trucker protests as a threat to democracy rather than a moment of democratic discontent. It’s the instinct that turns political opponents into irredeemable malcontents. And it’s the same one that now allows MacLean, in the twilight of Cherry’s life, to make a final public reckoning that centers not on his former friend and partner, but on himself.

None of this is to say that one should fully endorse Cherry’s views. I certainly don’t. His style was often abrasive, and his opinions were sometimes objectionable. But he also represented something undeniably real: a scrappy, populist, and yes, provocative part of Canada that continues to exist even if our elite institutions would rather pretend it doesn’t.

Cherry never claimed to be anything other than who he was. His views may have been controversial, but they were also reflective of a broader sentiment among many Canadians who feel increasingly alienated (and condescended to) by a cultural or political establishment that no longer speaks to them or for them.

Now Cherry is fading from the stage. But the bigger question, perhaps, is whether it’s MacLean who’s stayed too long. His role as the elder statesman of Canadian hockey broadcasting feels increasingly anachronistic—not because of his age, but because of his assumptions. The self-satisfied moralism, the rigid adherence to progressive orthodoxy, and the impulse to see the world only through the lens of identity politics.

In the end, Don Cherry may have been too rough for modern television. But at least he knew who he was, and didn’t pretend otherwise. MacLean, in contrast, seems increasingly unsure of who he is—except that he’s certain he’s right and that his lucrative TV contract will be renewed for another year.

Cherry may be stepping away. But maybe it’s time MacLean did too.