The U.S. is making policy decisions that should be sabotaging its economy. It has piled tariffs onto key inputs, stoked global uncertainty with its threaten-and-delay tactics, and President Donald Trump recently toyed with dismissing Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell—the individual responsible for keeping financial calm amid economic storms.

The U.S. isn’t just playing with fire when it comes to its economy; it’s fanning the flames. Global forecasts expect the U.S. to take an economic hit, but that hasn’t happened yet.

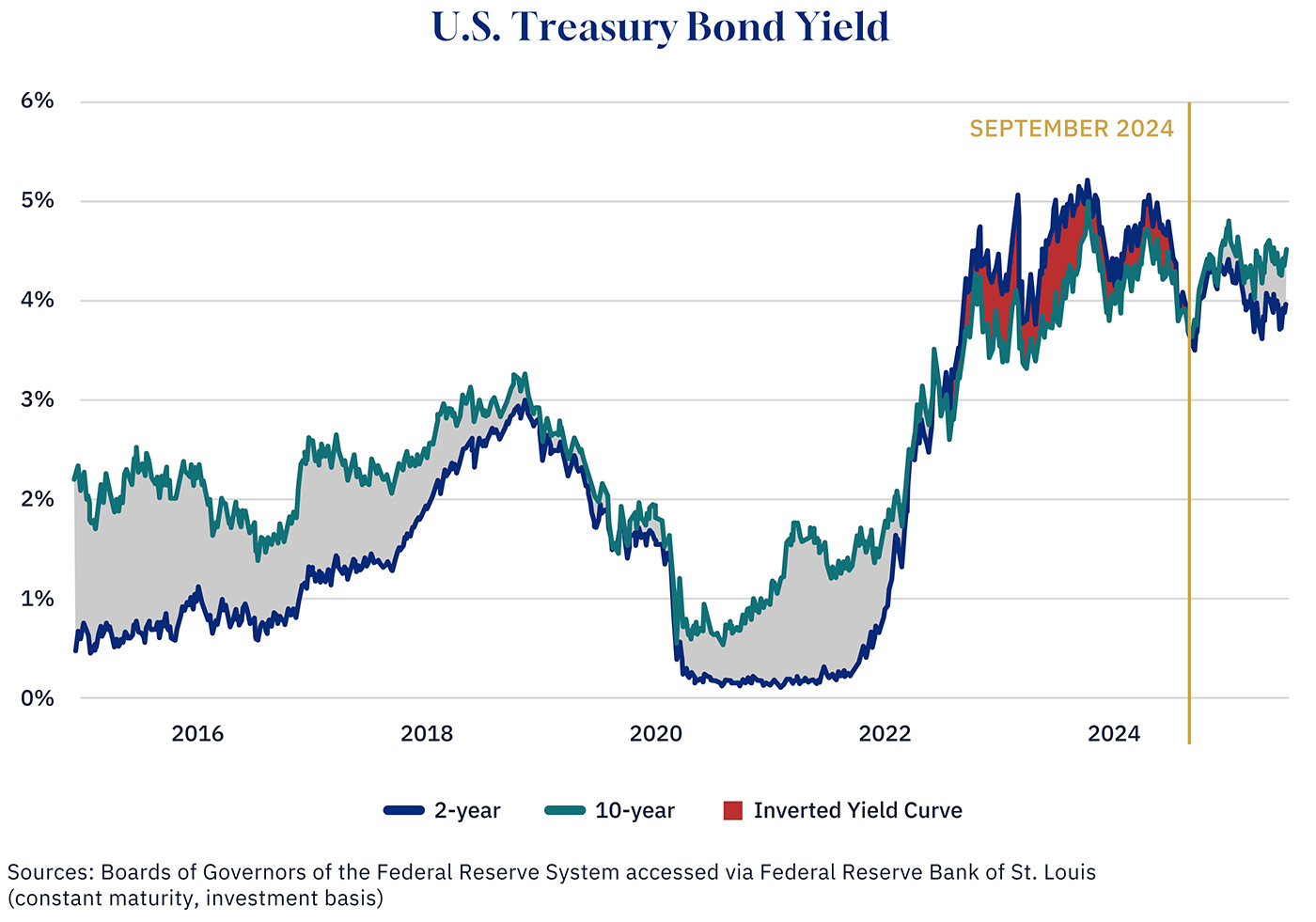

Could a downturn be looming? One way to see this is to examine the bond market—specifically, what’s known as the yield curve. The yield curve measures the difference in the return investors receive when they buy short-term versus long-term government bonds.

Right now, long-term bonds are paying more than short-term ones—exactly what we’d expect in a stable, healthy economy. It’s when the opposite happens that economists begin to worry.

Before explaining why, it’s worth taking a quick step back for those of us who don’t live and breathe bond markets to talk about how they work. A bond is like an IOU. When you buy one, you’re lending money to the government, which promises to pay you back the bond’s value plus interest. But the market price of that bond can vary, changing the actual return you make. A cheaper bond typically yields a higher return, and vice versa.

The reason a 10-year bond typically pays a higher return than a two-year bond is simply because 10 years is a long time to wait, and a lot can change. The higher return makes it worth your wait and the risk.

When this pattern flips—when long-term bonds start paying less than short-term ones—economists get concerned. This “inverted” yield curve can be an early indicator of a recession.

Essentially, what happens is this: when investors are worried, they turn to long-term bonds to lock in today’s higher returns before they drop. In a weakening economy, interest rates and inflation typically fall—both of which reduce future bond returns. So, the idea is to grab the higher returns now and lock them in for as long as possible.

However, as people rush to buy longer-term bonds, this drives up their price, while the interest payment remains the same, thereby decreasing the actual return for the investor. If you pay $1,200 for a $1,000 bond with a $50 annual interest payment, your yield is no longer 5 percent.

Looking at the data: the yield curve was flashing red from 2022 into 2024, with two-year bonds yielding more than 10-year ones. But since last summer, that light has faded. Even amid trade turmoil earlier this year, 10-year yields held strong—and in recent months, the gap has only widened.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

This could mean everything’s fine—or it could be that another force is at play. That returns remain so high has led some to think investors are starting to question the U.S. government’s ability to repay its debt. If no one wants to buy bonds because they think they’re too risky, prices fall, and the return, therefore, goes up.

That idea is not entirely far-fetched. Back in May, Moody’s—one of the major credit rating agencies—downgraded the U.S. government’s credit rating. Since then, the government has piled on yet another $2 trillion US to its already-high $36 trillion debt with the passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill. And that could look more like $3 trillion once you factor in the higher borrowing costs required to entice investors to keep lending money to the U.S. government. That’s the kind of thing that, even for a once-trusted borrower, can turn debt into a downward spiral.

So while the yield curve might look okay for now, it could be revealing another issue—that trust in U.S. government finances is starting to fray.

A version of this post was originally published by the Business Council of Alberta at businesscouncilab.com.