DeepDives is a bi-weekly essay series exploring key issues related to the economy. The goal of the series is to provide Hub readers with original analysis of the economic trends and ideas that are shaping this high-stakes moment for Canadian productivity, prosperity, and economic well-being. The series features the writing of leading academics, area experts, and policy practitioners. The DeepDives series is made possible thanks to the ongoing support of the Centre for Civic Engagement.

Canada’s foresight failures

When Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, nations around the world implemented sanctions on it, including prohibiting or limiting purchases of Russian gas. Then-German chancellor Olaf Scholz met with Prime Minister Trudeau to discuss if and how Canada could supply gas to Europe to replace Russian supply and enable our NATO allies to cripple Russia’s economy and war effort. Canada had no answers, with Trudeau only able to respond that Canada would need a “strong business case” to develop the capability to export LNG to Europe.

The United States exported 6.3 billion cubic feet of LNG per day to Europe in 2024 alone—about 13 billion USD worth. Canada made its first-ever LNG export in June this year—to Asia, though, not Europe.Rabinovitch, “What is liquefied natural gas?”

Canada’s belated entry into LNG exports underlines not only a missed economic opportunity, but a failure to act in the global good and support our allies. Could Canada have foreseen Russia’s dramatic escalation of their conflict in Ukraine? In the months leading up to it, yes. But early enough to have developed LNG export capabilities? Probably not. But that is just the specific scenario that arose. When thinking about LNG exports a decade ago, we could have asked:

- Will another major energy exporter face major sanctions?

- Will the United States develop enough domestic capacity to no longer require Canadian exports?

- Will the transition to green energy globally take long enough to require Canadian gas for decades to come?

Getting the answer right to these questions would have put Canada in a position to take advantage of the opportunity presented by Russia’s aggression.

Canada’s LNG export failure is just one example of how a practice of strategic foresight could have benefited Canadian citizens, businesses, and our international allies. As global geopolitical power shifts move the world from unipolar to bi- or even multi-polar order, more crises and opportunities are bound to present themselves. Canadian governments and businesses need to use proven tools of foresight to survive and thrive.

Let’s take a deep dive into the state-of-the-art foresight tools that governments should be using to navigate a world of growing complexity and uncertainty.

Development of the tools of foresight

In the last several decades, governments, intelligence agencies, and businesses have developed a variety of tools for how to think about the future and what it might bring.

Herman Kahn is frequently cited as one of the key thinkers behind early foresight developments, particularly scenario planning. When nuclear war became a real threat at the start of the Cold War, clear, structured thinking about the future became more important than ever. Working at RAND Corporation and later at the Hudson Institute, Kahn did extensive work on how nuclear war might occur and how the U.S. could react to and survive such an attack.

The corporate sector soon realized that Kahn’s work could be applied beyond military uses, and in the mid-60s, Ted Newland and Jimmy Davidson of Shell began researching alternative futures, creating Shell’s scenarios program. Famously, Shell’s future-focused insights would help them successfully navigate the 1973 oil crisis.

At the same time that scenario planning was being developed, intelligence agencies were considering how they could think systematically and ensure they didn’t miss key information in the endless flow of intelligence that came their way. The CIA has publicly available resources on tradecraft, including many of the techniques that were developed over this period.

In the last couple decades, the foresight community has begun to partner with experts in forecasting to combine the two fields and create a potent method of imagining and evaluating the likelihood of future events. Crowd-sourced forecasting was popularized by Philip Tetlock & Dan Gardner’s Superforecasting, which summarized research conducted by the U.S. intelligence community in the early 2000s demonstrating that teams of individuals using only open source intelligence could collectively create highly accurate forecasts—sometimes even more accurate than intelligence analysts with access to classified information.P.E.Tetlock, D.Gardner. “Superforecasting” (2015): 73-73

Samples of foresight tools

Issue decomposition

As developed in CIA analyst Richard Heuer’s The Psychology of Intelligence Analysis, decomposition is the practice of breaking down a large, complex question into its constituent parts which can then be researched and analyzed more manageably. This process is often used to enable other types of analysis, such as scenario planning.

As with other structured analytical techniques, decomposition helps analysts avoid common human biases. By studying a topic’s component parts individually and in relation to each other, analysts can remain disciplined and comprehensive in their approach. For example, it prevents giving too much weight to a particular factor that might be more obvious in an initial analysis, but less salient upon further examination. Practically, decomposition yields a number of benefits:

- Uncovers hidden risks and dependencies

- Provides an organized framework to coordinate thinking across an organization

- Enables organized monitoring changes in a broad issue through its drivers & indicators

- Ensures analysis remains focused and actionable

In the intelligence world, decomposition can mean the difference between a general concern about a terrorist attack and identifying specific weaknesses that could be targeted or particular terror cells with imminent attack potential. In the business world, it can help convert endless, high-level discussions about the impact of AI on an industry into specific conversations that deliver real insight and actionable tasks.

Scenario planning

Also derived from intelligence practices, scenario planning, or alternative futures analysis, is a creative form of analysis that enables individuals to consider the future in an ordered, systematic manner. Importantly, scenario planning does not involve predicting the future, but rather identifying possible futures to enable decision-makers to prepare for risks or drive their organization toward new opportunities.

Best performed with a small team involving both analysts and decision-makers, scenario planning enables teams to identify “known unknowns” and uncover some of the “unknown unknowns” made famous by Donald Rumsfeld’s awkward 2002 news conference: “the ones we don’t know we don’t know.”

Scenario planning analysis involves several steps:

- Research: a team of analysts conducts research ahead of time to gain foundational understanding of a given topic.

- Discuss: a team of analysts and decision-makers is formed to ensure a broad array of views are heard from all stakeholders.

- Synthesize: discussion is distilled into a decision matrix to structure further discussion.

- Develop: scenarios are developed in further detail, including how a particular scenario would develop and the potential results.

- Recommend: actionable recommendations are provided for possible risks and opportunities.

- Monitor: scenarios are monitored to determine which are occurring and what future steps should be taken.

In the intelligence world, scenario planning has been used for wide ranging purposes, from considering the future (and fall) of the Soviet Union to the U.S.’s 2011 bin Laden raid, allowing preparation for worst-case scenarios and enabling key decisions to be made in high-stakes circumstances with a wide range of possible outcomes.

Of course, the use case for scenario planning is not limited to intelligence and military operations. Just as Shell used scenario planning to help manage through the 1973 oil crisis, UPS’s scenario planning practice allowed it to take advantage of the 1990s-2000s boom in e-commerce.

Crowd-sourced forecasting—the cutting edge

At first glance, moving from identifying possible futures to actually predicting them seems like a leap—and for good reason. We are used to seeing pundits on TV making grand predictions that fall flat, and then the very same pundit returns with yet another prediction, year after year, with no accountability. However, not all predictions are made the same.

Just as weather forecasts have improved with advancements in science and technology (short-term forecasts are now remarkably accurate, even if meteorologists remain the butt of many jokes!), so too have geopolitical forecasts, when done correctly.

One of the first realizations that a group of individuals—a “crowd”—could create accurate forecasts came from Sir Francis Galton in 1906. At a country fair, there was a competition to guess the weight of an ox. Taking all the betting slips afterward, Galton found that the average of the nearly 800 guesses was just one pound away from the true weight (1197lbs versus an actual 1198lbs).

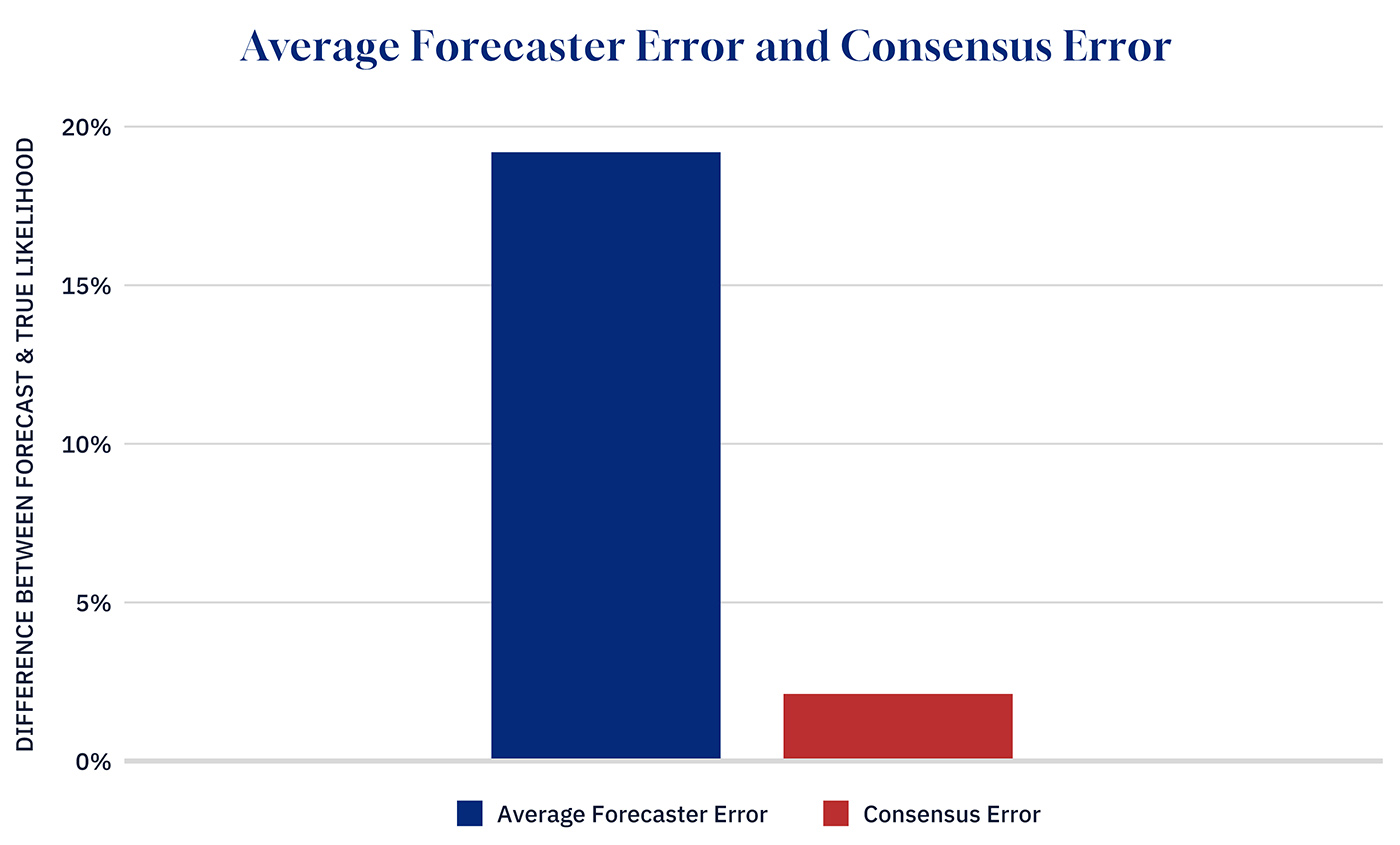

Building on this concept in 2005, James Surowiecki would later write in “The Wisdom of the Crowds” that a large, intellectually diverse group of people can be collectively smarter and less biased than individual experts. Further study has shown that while an individual may outperform a crowd consensus on a given prediction, crowds consistently outperform individuals across a set of questions by at least 20 percent.Simoiu, C., Sumanth, C. et al. (AAAI 2020). Studying the “Wisdom of Crowds” at Scale in Proceedings of the 7th AAAI Conference on Human Computation and Crowdsourcing.

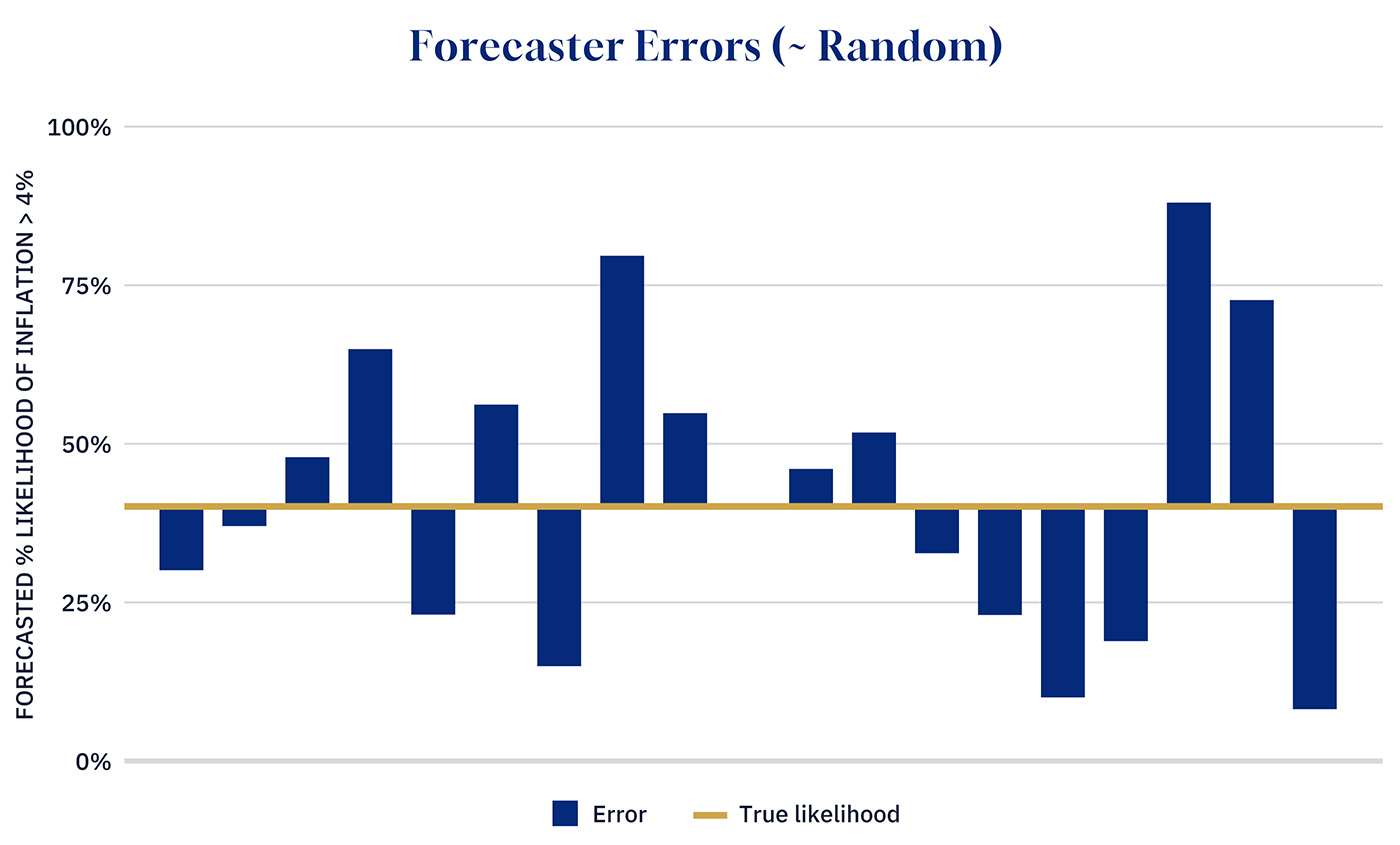

The cause of this is that forecasters each provide different information through their forecasts, based on their own thought processes, research, and experience. In an intellectually diverse crowd, individual forecasters’ errors are effectively random. However, the “correct” useful information forecasters provide all points in the same direction, acting in an additive manner and resulting in a highly accurate consensus.

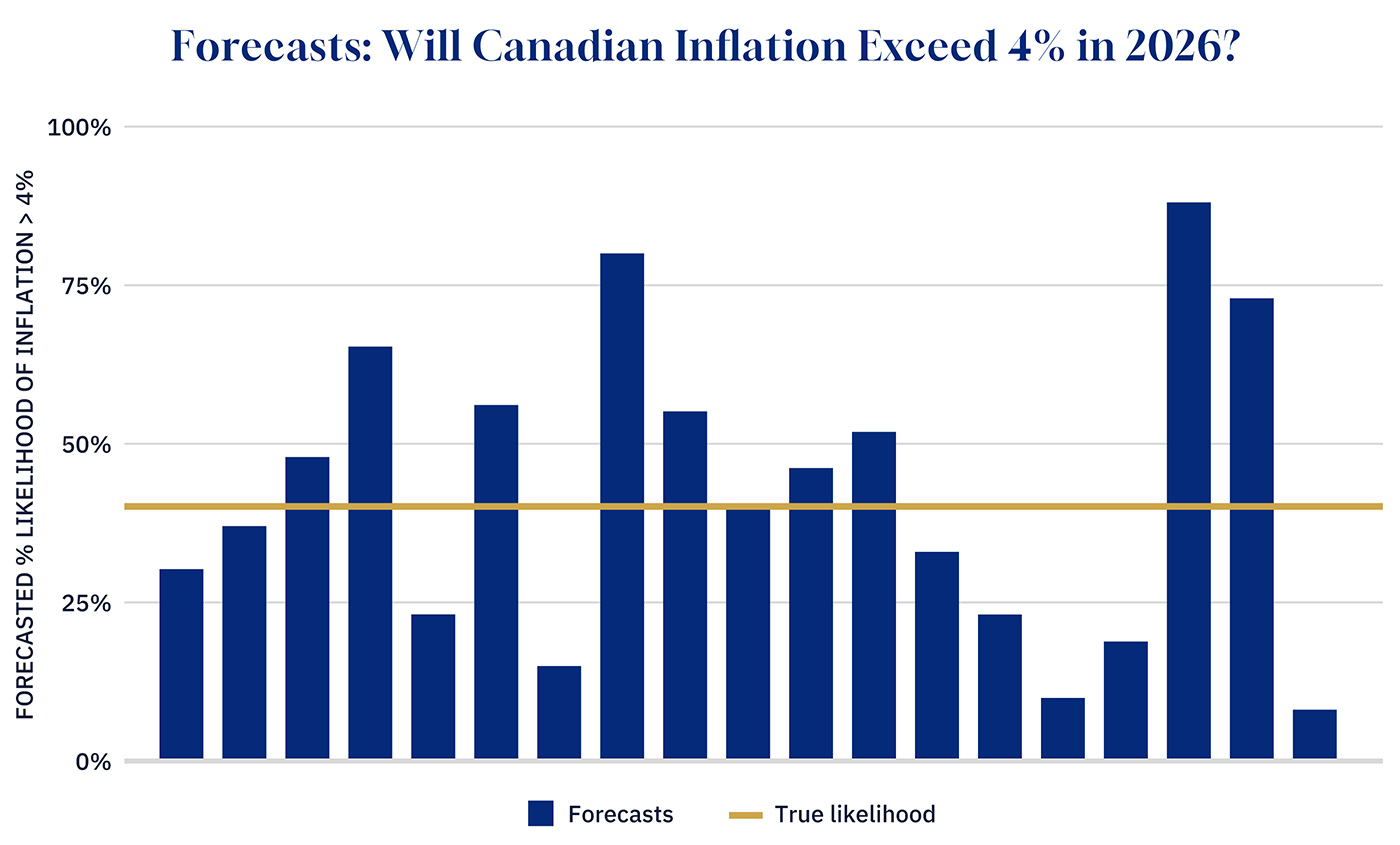

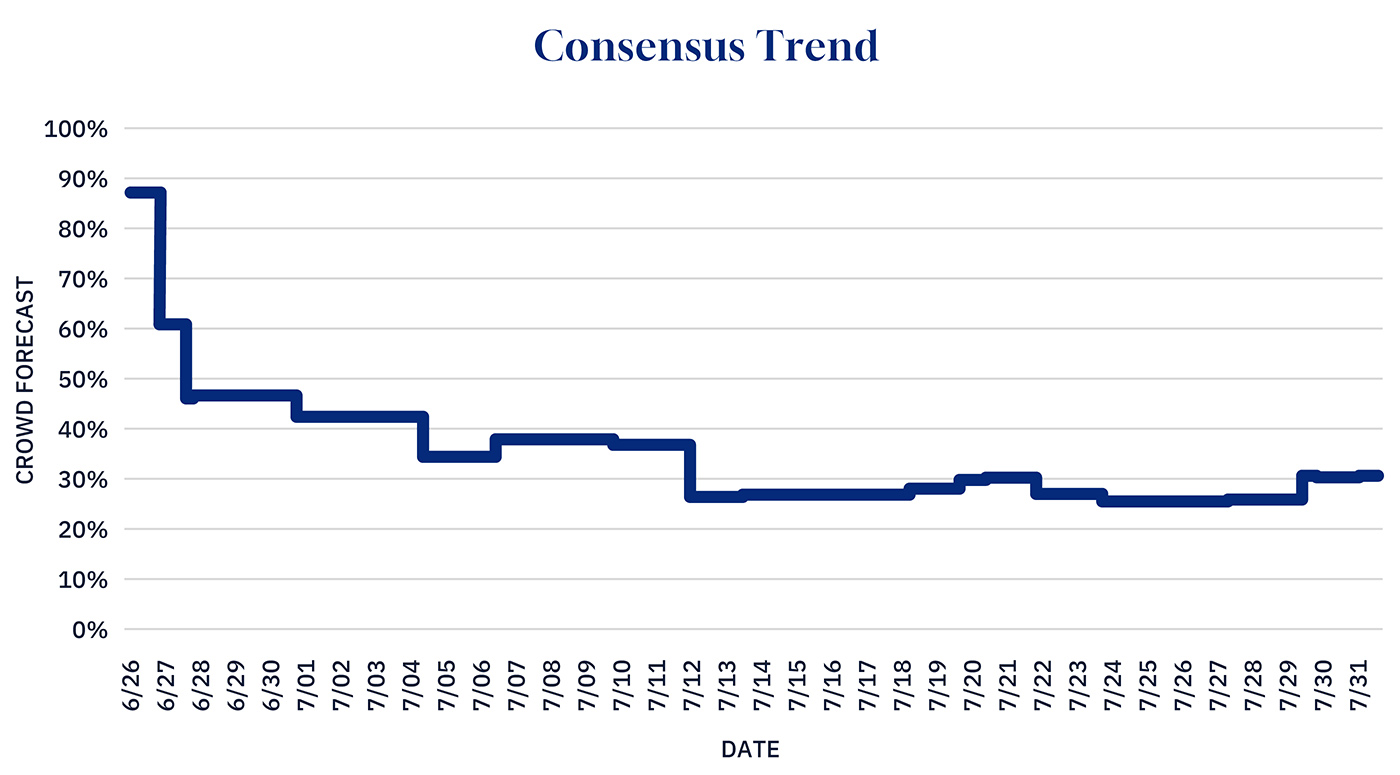

The below charts show the “wisdom of crowds” effect in a hypothetical example. If you asked a diverse group of forecasters what they thought the probability would be that Canadian inflation would exceed 4 percent in 2026, their estimates would range considerably. In the first chart, we see that these range from an over 75 percent certainty to less than 20 percent, despite the “true” probability being a 40 percent chance. Despite the wide ranging errors, the random error variability effectively cancels itself out, and the group consensus is much closer to the true probability compared to a given individual’s view.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

Modern crowd-sourced forecasting efforts typically involve one of two methodologies: scored forecasting and prediction markets. In scored forecasting, participants receive a score based on their accuracy relative to the crowd. This allows for healthy competition and once a baseline level of accuracy is established, the weighting of future crowd consensuses by accuracy. Prediction markets are effectively betting markets, where predicting the correct outcome can result in winning real (or fictional) currency. While both methods achieve a similar goal by aggregating the opinions of many individuals, prediction markets tend to be less transparent.

Both methods routinely predict election outcomes across the globe, and governments, intelligence organizations, and think tanks use forecasting platforms to aggregate predictions on everything from terrorist attacks to civil wars. In the corporate sector, Fortune 500 firms source forecasts on resource extraction, competitive threats, and even the success rate of pharmaceutical drug candidates.

At Cultivate Labs, we provide the technology and consulting behind major forecasting efforts in governments and corporations across the globe, as well as public forecasting sites for RAND, the Bertelsmann Foundation, and Good Judgment.

Foresight in practice

Decomposition and scenario planning

While intelligence organizations can employ armies of analysts to perform structured analytics, time and personnel remain one of the biggest obstacles to implementing rigorous analysis at smaller organizations and even large ones when their sole focus isn’t analysis. As a result, either the analysis is never performed, or it is completed too late to be a useful tool for decision-makers.

Though building out a large, comprehensive analysis team is always an option, advances in AI are extending the reach of individual analysts, enabling them to do more, more quickly. AI-powered analysis tools can now process far more information than an individual analyst and create first drafts of decomposition and scenario planning outputs in minutes. While human analysts will likely always be required to confirm analysis and make decision recommendations, AI now enables individuals and small teams to produce the kind of quality work that formerly required either weeks of work or large teams of analysts to produce.

Forecasting: mechanics

AI isn’t ready to compete with human intelligence in forecasting, and it might never be, making humans a key part of the foresight toolkit both now and in the future. Fortunately, crowdsourced forecasting has been practiced for years, and setting up a platform like RAND’s industry-leading Forecasting Initiative is straightforward.

Forecasting platforms ask users for probabilistic forecasts on specific, answerable questions, such as when a Russia-Ukraine ceasefire may take effect, or what inflation will be in the U.S. next year.

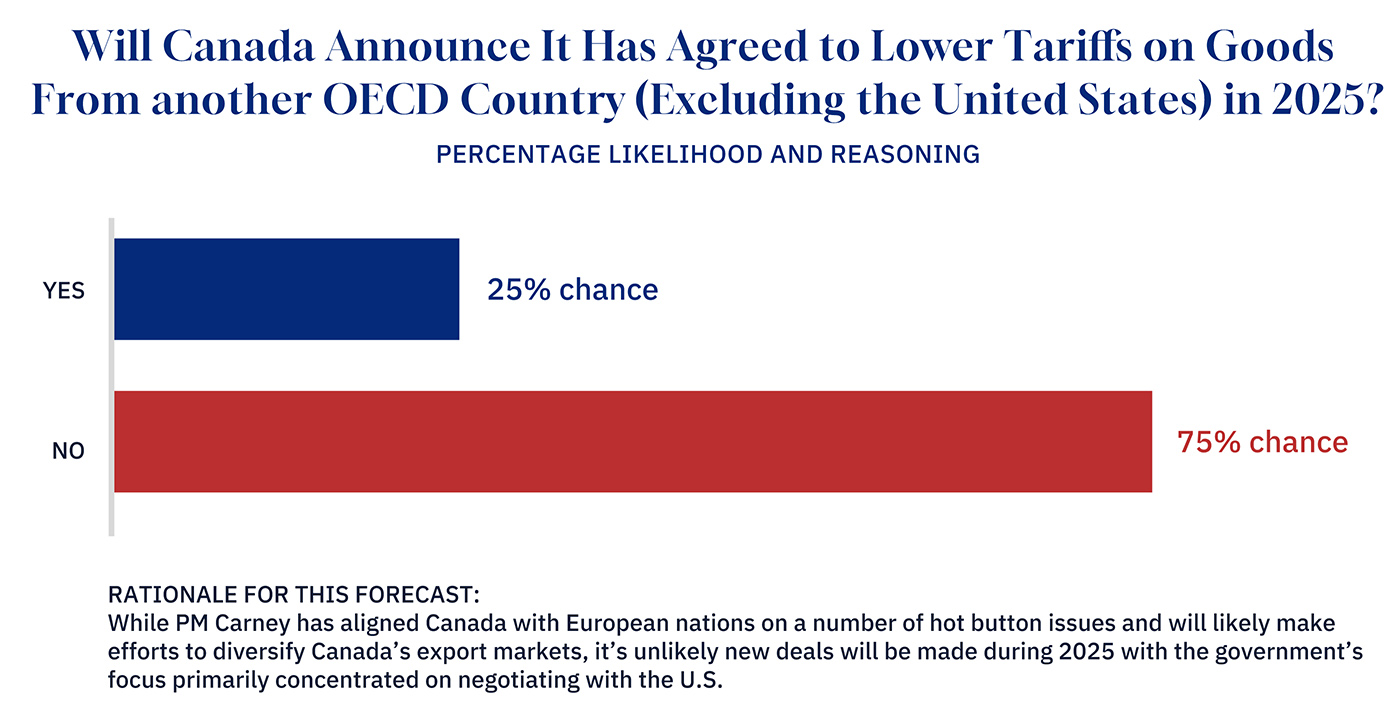

In Canada’s current trade predicament, a pertinent question might be: “Will Canada announce it has agreed to lower tariffs on goods from another OECD country (excluding the United States) in 2025?”

Forecasters—sourced from the general public, an organization’s staff, or a pool of professional forecasters—then respond with a percentage likelihood and their reasoning:

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

The crowd’s forecasts are combined into an accuracy-weighted consensus forecast, which updates live as new users forecast and previous forecasters amend their positions. Together with the written rationales that users are prompted to write, forecasting platforms provide robust, current forecasts with transparent reasoning and sourcing.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

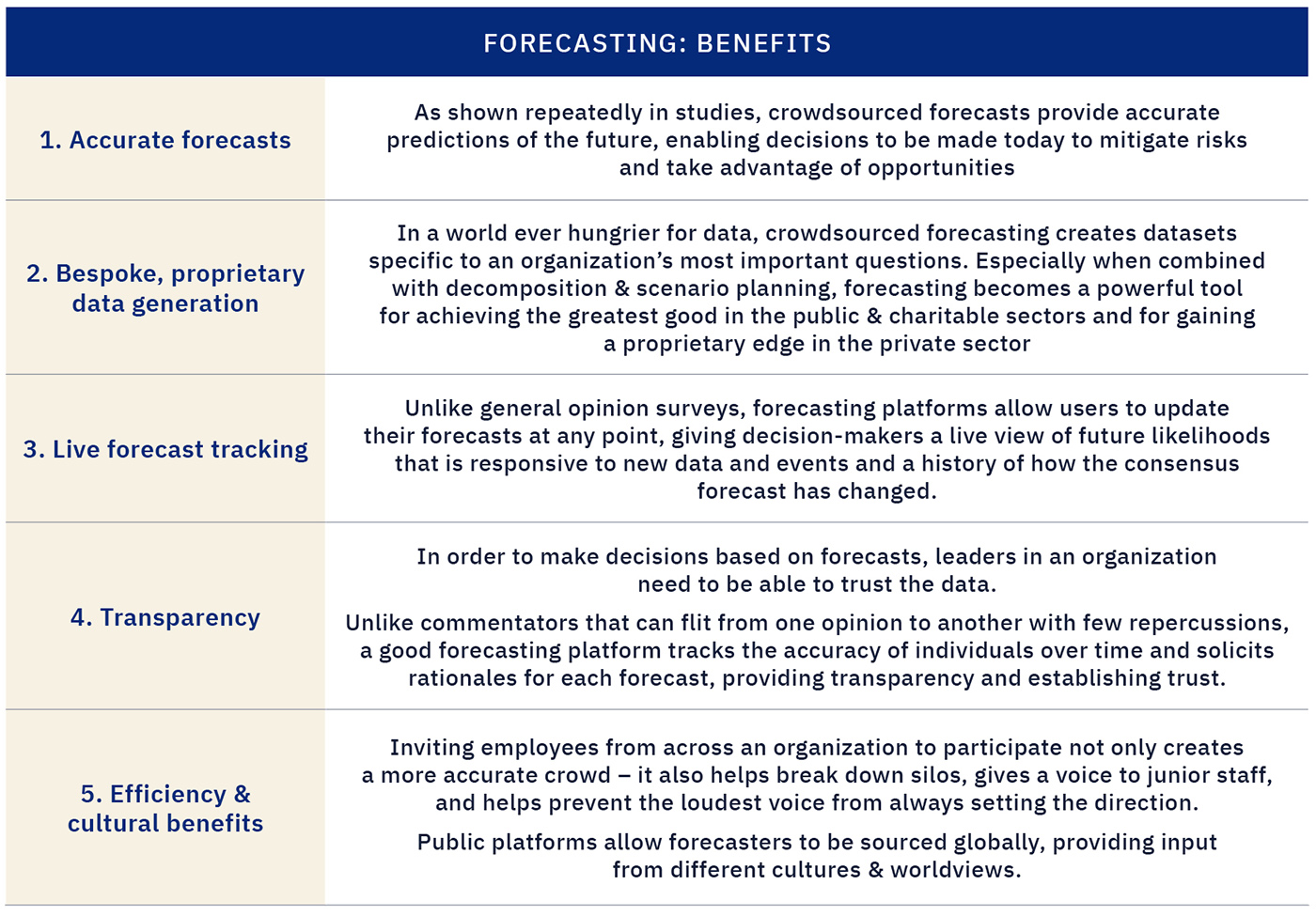

Forecasting: benefits

Whether exclusively using an organization’s own staff or seeking global input via a public platform, crowdsourced forecasting delivers practical results:

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

Putting it all together

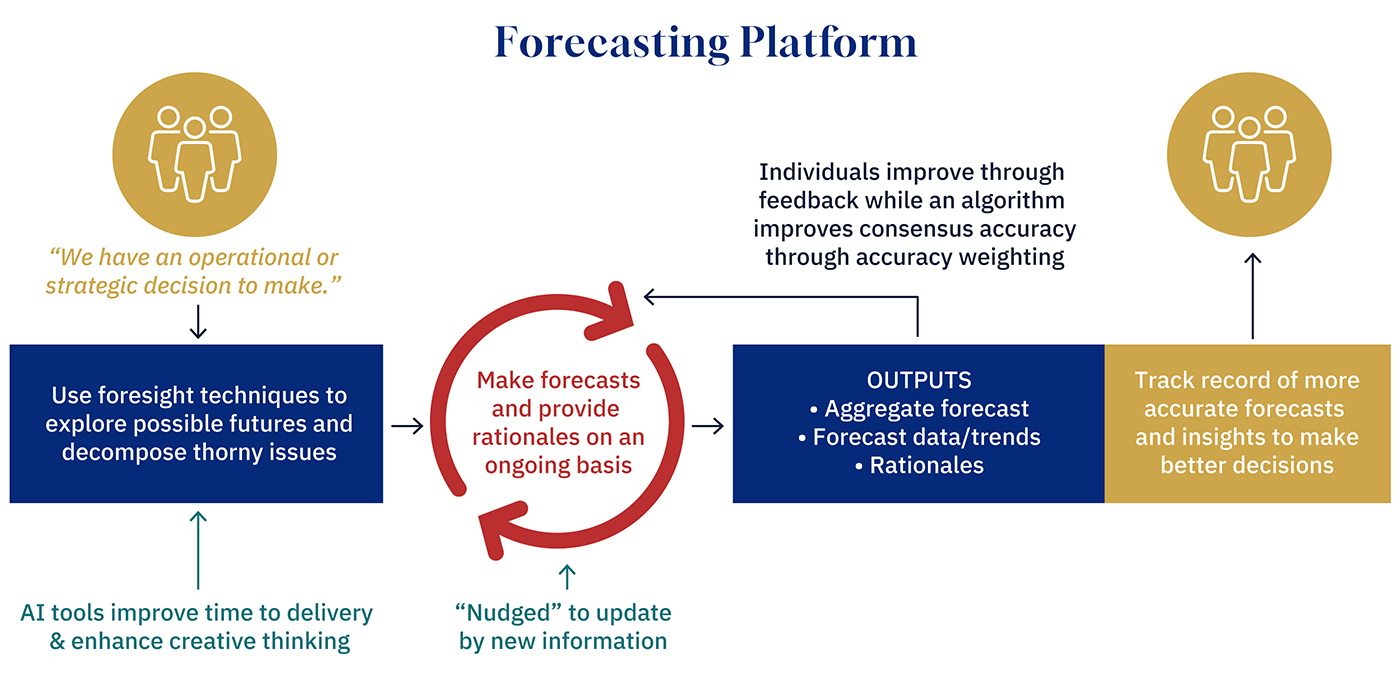

As one can imagine, foresight tools work best in concert with each other. Scenario planning enables analysts to creatively consider possible futures, decomposition determines the key factors that will determine what future we ultimately experience, and forecasting relevant sign-posts gives a data-driven glimpse into which scenario is most likely to occur—and allows decisions to be made based on the best possible information.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

Key takeaways

The world is responding, not only to the immediate crisis of the day—President Trump’s tariff policies—but also to the gradual progression from U.S. hegemony to a reality where China and other nations wield more economic, military, and political power. In this tumultuous climate, strong foresight practices will be key to enabling better decisions today for a safer, more prosperous future.

Some Canadian organizations have followed their international peers and taken steps to improve their foresight capabilities in specific areas—the Canadian Forest Service runs an internal forecasting program to improve prediction capabilities within the service, for example.

Canadian politicians and businesses would be well served by following their example and building a stronger Canadian foresight and forecasting community.