For most of the last decade, Canada’s housing debate felt like a bad dream. Prices sprinted ahead of incomes, young families quietly gave up on the idea of space, and governments offered promises that sounded more like slogans than solutions.

Then, improbably, the last two years delivered something different. Circumstances shifted: higher interest rates cooled speculation, and economic uncertainty took the heat out of demand. At the same time, governments finally acted. Ottawa cut the GST on new purpose-built rental housing, unlocking projects that had been stuck on the shelf. Immigration reforms pared back temporary resident inflows and adjusted permanent resident targets, easing pressure on household formation. CMHC dramatically expanded its lending programs, driving a historic wave of financing for apartments. Provinces and municipalities, meanwhile, began loosening zoning rules and streamlining permits.

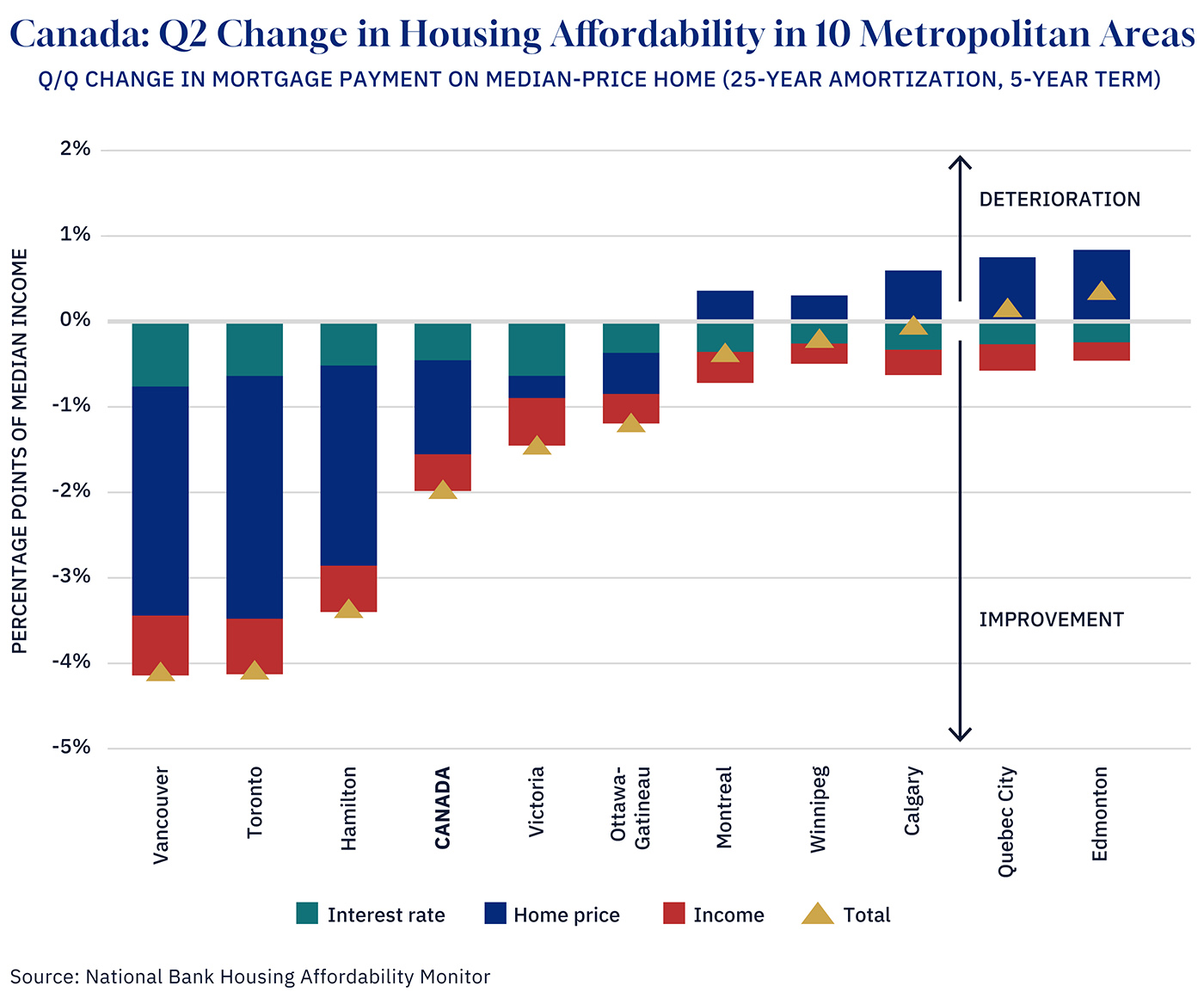

Together, these changes matter, even if they can go far further. For the first time in years, affordability—still bad—stopped getting worse and is moving in the right direction.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

That’s real progress, and we should say so, because this country’s reflex is to skip over the good news and sprint straight to despair. But the easy part was turning the wheel. The hardest part is the landing, steering through a correction without flattening builders, homeowners, or the broader economy.

Canada’s problem children risk the nation

The picture across Canada is uneven. Alberta is booming, Atlantic Canada and Quebec are building at record pace, and Saskatchewan is holding its own. These regions prove that when costs line up and approvals move, housing actually gets built. But Ontario tells a very different story. Toronto—the country’s largest housing market—has seized up. Pre-construction sales are down more than 80 percent, new project launches have nearly vanished, and inventory is piling up. Vancouver is beginning to wobble as well. And of course, those are precisely the markets where Canada needs the most new homes.

On paper, falling prices look good. But corrections don’t land neatly; they land on people. Families who bought at the peak are staring at negative equity, owing more on their mortgages than their homes are worth. That doesn’t just bruise a balance sheet—it freezes a life. You can’t move for work, can’t upsize as kids arrive, can’t refinance without taking a loss.

Builders are pulling back as well. Toronto’s model of pre-selling towers to investors in order to finance construction depends on demand that has now evaporated. Projects that looked viable three years ago no longer pencil out. Some developers are already in receivership, most are simply on pause, and an industry that employs hundreds of thousands of blue-collar and unionized workers sees demand evaporating before their eyes.

With new starts collapsing, the pipeline of work is drying up. Layoffs follow, skilled trades scatter to other industries or retire early, and when demand returns, as it inevitably will, we’ll have lost the workforce we need to build at scale again.

The financial system is not immune either. Canadian banks are well-capitalized, but they’re already flagging rising delinquencies and bracing for stressed developers. Private lenders are shakier still. Defaults and fire sales could ripple outward, undermining confidence in a sector that anchors household wealth and tightening credit for years to come.